BY ANIBE IDAJILI AND OUSMAN A. MARONG

The sun in Kontagora, a town in Nigeria’s Niger state, felt like a premonition of an impending violation one afternoon in March 2025. Amina was just a four-year-old girl with innocent, bright eyes until everything changed, tragically.

The man who did it was not a stranger but Isah, a 37-year-old family friend, who had eaten at their table and earned their trust. He lured Amina with the promise of candies, something small to make her smile. But what he took from her was a fundamental part of her being. He raped her!

When her mother found her later, Amina could not speak. The words had been stolen from her by the pain and confusion she felt. Not even her aunt, Hadiza, could gather enough courage to speak up for her.

Advertisement

“What will people say?” Hadiza had whispered. “Her future will be ruined if this gets out.” In so many communities across Nigeria, survivors of child sexual abuse (CSA) are hushed, their pain buried under layers of stigma and fear.

Amina’s silent struggle in Kontagora is mirrored by different, yet equally urgent, battles for safety and bodily autonomy playing out across West Africa, including a recent legislative triumph hundreds of miles away in The Gambia.

THE DEEPENING CRISIS

Advertisement

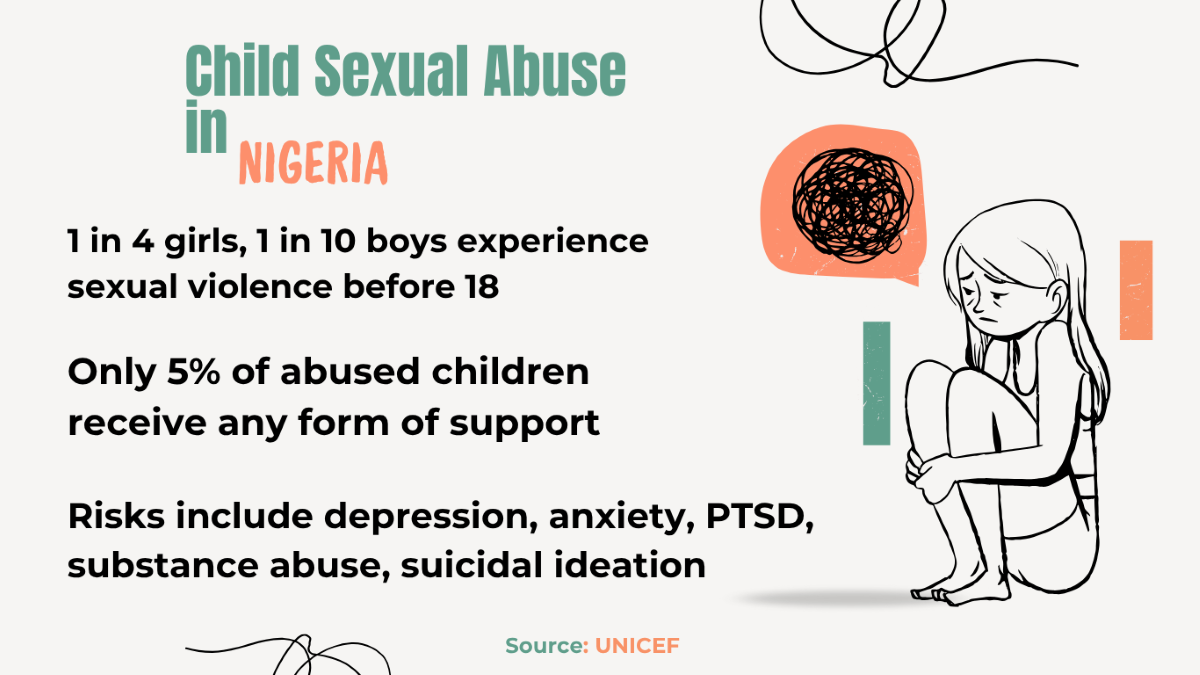

By age 18, one in four girls and one in 10 boys in Nigeria fall victim to sexual activity they are too young to consent to. Of the children who reported this violence, fewer than 5% ever receive any form of support. Despite long-term consequences like heightened risks of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, and suicidal ideation, the true scale of CSA remains largely obscured by fear and the shame associated with sexual assault across Nigeria.

But amidst this widespread silence, a dedicated coalition is forging a path to healing in Kontagora, demonstrating that community-driven solutions can offer a helping hand where systemic support fails.

COALITION OF CARE

Advertisement

When a friend told Hadiza about the coalition helping children like Amina get medical help and justice, the family decided to take the chance.

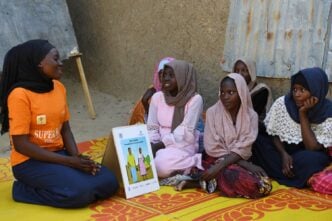

The grassroots coalition — comprising three local nonprofits, the Rayuwa SARC (Sexual Assault Referral Centre), the Kontagora General Hospital, the Social Welfare Unit of Kontagora Local Government, and law enforcement agencies — have built a proactive network of care, ensuring survivors like Amina get the needed support. They offer free medical attention, counselling, and family support, recognising that rescue and recovery often require seeking out survivors.

Upon receiving a report of child sexual abuse, the coalition ensures survivor safety through immediate connection with the minor and their guardian, offering a confidential, supportive space. Team members facilitate free medical exams for evidence documentation, treatment, and infection prevention, as well as age-appropriate counselling for emotional and psychological support. Collaborating with community leaders, they also run awareness campaigns to educate residents on identifying CSA, dispelling myths, and promoting collective responsibility in child protection.

“Unlike conventional health services that rely on survivors to seek help, their volunteers conduct phone calls and even home visits,” said Bashir Kabir, a Kontagora resident.

Advertisement

“We understood that stigma and geographical distance are huge obstacles,” explained Hussaini Muhammed, the founder of Good Leadership and Empowerment Awareness Initiative (GLEAI) and a member of the coalition. “Many families in rural areas can’t easily reach health centres, or they are too ashamed. Our job is to demystify the process.”

Fatima Aliyu, head of the welfare unit at the Kontagora Local Government Secretariat, confirmed the medical intervention: “We send survivors to the General Hospital where they are provided with routine screening, post-exposure prophylaxis, antibiotics, counselling, and contraceptives. We also counsel parents on the benefits of early intervention, ensuring they support, rather than stop, the child’s recovery.”

Advertisement

Since its launch in 2023, the programme has provided care to 27 survivors of childhood sexual violence. “Each child we have intervened for represents a victory against CSA,” Muhammed said.

For Amina and her family, the coalition’s intervention meant immediate medical care and counselling, but it also opened a path towards justice.

Advertisement

With the coalition’s effort, Isah was apprehended and is currently in police custody, awaiting trial at the magistrate court in Kontagora for contravening Section 19 (1) and (2) of the Child Rights Act (2023). The family, though still reeling from the trauma, holds onto the hope that a conviction will bring some measure of closure.

LEGISLATIVE HURDLES

Advertisement

However, the journey is far from over. While the programme excels at initial care, it faces significant limitations in providing the sustained, long-term psychological support needed for deep trauma. Furthermore, the fight for accountability is often lost in systemic failure.

These challenges are compounded by a legislative flaw: Niger state is yet to domesticate the Violence Against Persons Prohibition (VAPP) Act 2015. This legal gap, alongside constitutional inconsistencies regarding the age of marriage, collectively undermines efforts to protect children and hold abusers accountable.

Although the Child Rights Act (2003) prohibits marriage below the age of 18, many states, particularly those with Islamic legal systems, have failed to adopt this age limit for many marriages. This creates a legal void. In these states, there are claims that sexual relationships for girls below 18 are consensual within marriage, effectively legalising statutory rape.

The definitions of rape under the outdated Nigerian Criminal and Penal Codes also offer inadequate protection, meaning that pursuing justice for children like Amina is often elusive.

For minors whose abusers potentially face outdated, weaker penalties under the Penal Code, the lack of VAPP domestication means that a full path to justice and sustained support for their trauma remains tragically distant.

With this legislative deficiency, the fight for bodily autonomy and protection in Nigeria finds inspiration in a recent, hard-won Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) victory just across the West African sub-region in The Gambia.

UPHOLDING FGM BAN IN THE GAMBIA

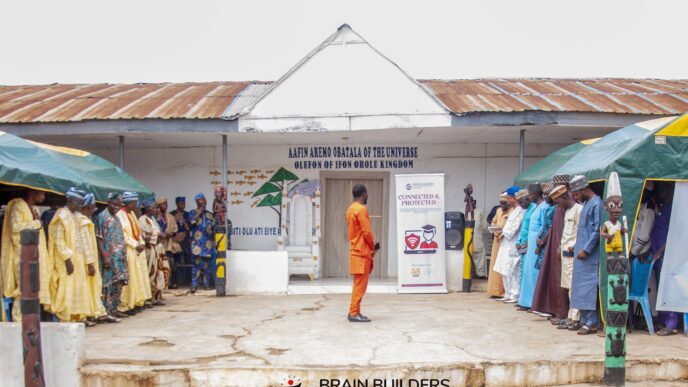

While Nigerian activists tirelessly push for the domestication of the VAPP Act to protect children from sexual violence, the Gambian SRHR advocates recently secured a landmark win concerning another form of gender-based violence, Female Genital Mutilation (FGM).

In July 2024, The Gambia’s parliament made the decision to retain the law prohibiting FGM, a victory against deeply rooted, harmful traditional practices.

For survivors like Mariama Sanyang, founder of ‘The Girls Agenda’, this retention was not just a political manoeuvre but validation. Sanyang shared her harrowing experience of being subjected to FGM at the age of six, describing the practice as one that causes severe pain and long-term infections that impact menstrual cycles and reproductive health.

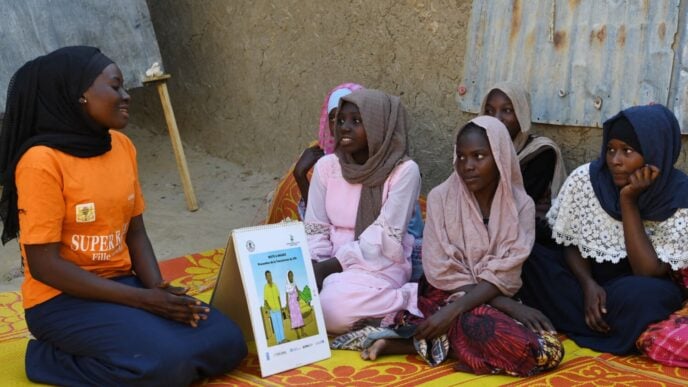

“The recent national campaign has played a significant role in ending female genital mutilation by raising awareness and promoting dialogue. We need to believe in survivor stories and understand that the harmfulness of FGM is not just hearsay,” Sanyang explained, emphasising the need for authentic engagement.

But according to Oumie Jagne of Think Young Women (TYW), a non-profit organisation in The Gambia that empowers young women and girls, the problem of FGM is deeply entrenched.

“Involving key stakeholders, including young men, boys, religious and traditional leaders, and women, is essential in this effort. Strengthening social media campaigns can also help inform everyone about the dangers of FGM,” Jagne said.

THE POLICY RESPONSE

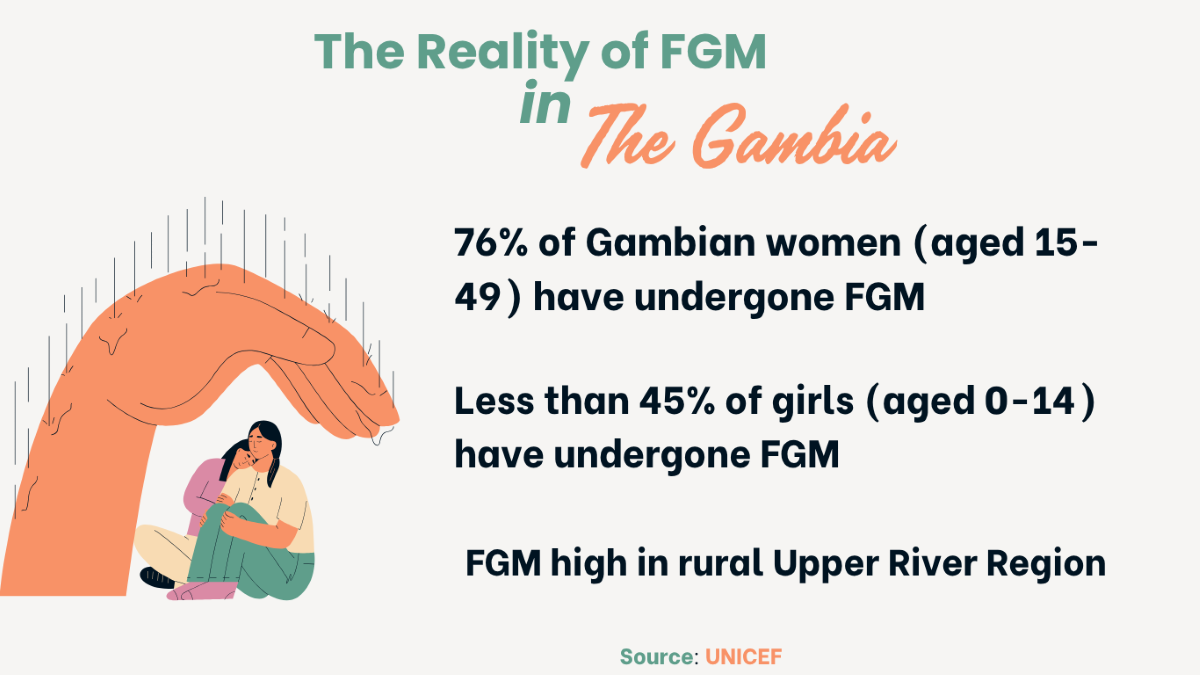

Based on UNICEF data, approximately 76% of Gambian women aged 15-49 have undergone FGM, mostly before the age of six. Among girls 0-14, the rate has declined to around 45% resulting from a National FGM Strategy and Action Plan for 2021-2025, which addresses gaps in the implementation of legislation that bans FGM, community outreaches promoting the elimination of the practice, and empowerment programmes that equip girls with interpersonal, life and advocacy skills.

But it is still high, particularly in rural communities in the Upper River region and among specific ethnic groups such as Mandinka, Saharauli, Jola, and Fula. These figures highlight the urgency of sustained community outreach and policy work.

For Jagne, a national-led solution hinges on a comprehensive strategy. This involves strengthening laws through policy reform, launching education and awareness programmes across schools and communities, actively engaging community and religious leaders to challenge and redefine harmful norms, and supporting survivors by ensuring access to healthcare and social services.

However, the scope of this strategy demands coordination transcending advocacy groups, requiring governmental and international commitment.

The Gambian government, in conjunction with UNICEF and the Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Welfare, has, therefore, amplified its efforts, strengthening laws, raising awareness through collaborations, and supporting community-led initiatives.

A LIMITATION CALLED CULTURAL DIVIDE

Despite the legislative victory, the debate shows the cultural and religious resistance activists face.

“The Gambia was built by different ethnic groups. All of them were practising FGM. This was in the centuries,” said Imam Abdoulie Fatty, a pro-FGM activist and prominent voice against the ban, arguing that the practice is intertwined with The Gambia’s cultural and religious heritage while questioning the Western perspective on harm.

“The harmfulness that both the WHO and UNICEF are talking about, let me remind them that a part [of the male that] is cut off [during circumcision] is much more than the one that is cut off [in] the female. Why are they (the West) not telling us male circumcision is also harmful?”

Imam Fatty’s stance highlights the deep-seated ideological opposition that advocacy groups must continually confront, even with the law on their side. He warned: “We (Gambians) have nothing other than our religion, and no amount of threat to lose USAID or subvention would ever stop us from doing the practice.”

However, his position that FGM is harmless directly contrasts the tragic reality on the ground. There have been at least two reported deaths, including that of a recent one-month-old infant in Wellingara, a small community in the Central River region of The Gambia, due to FGM complications. Another reported case occurred in 2016, where a child reportedly died after being cut in Kiang Sankandi. Additionally, there is a mention of a five-month-old baby who died in Sankandi Village due to FGM.

SHARED STRUGGLES AND LESSONS

For survivors like Mariama Sanyang in Banjul, The Gambia, the legislative victory offers affirmation and a clear path toward long-term cultural change. But for four-year-old Amina in Kontagora, Nigeria, the future remains uncertain. Though local heroes rushed to offer her first aid and psychological support, the lack of the VAPP Act means her abuser may walk free. This is a devastating reminder that while community care provides the necessary band-aid, only legislative courage can promise systemic healing and lasting justice across West Africa.

The true solution, however, lies in the fusion of legal frameworks with community-led approaches, a lesson Nigeria can learn from The Gambia’s legislative courage, and The Gambia can learn from Nigeria’s grassroots care models.

This story was made possible by the Nigeria Health Watch with support from the Solutions Journalism Network, a non-profit organisation dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.