A day after Maiduguri

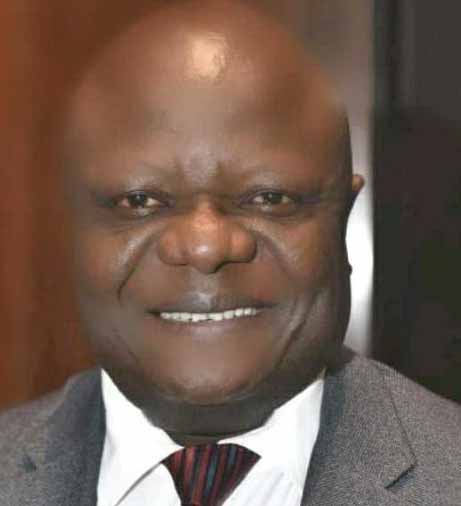

BY Abiodun Adeniyi

“Please will you be available for a one week research endeavour in Maiduguri?” The voice from the other end of the telephone said. “Madui .. What?” I screamed, in what made the caller think he was sentencing his listener to death. “Maiduguri is not what you think anymore. The place is calm, and flourishing, with many foreign workers doing their thing. I have been there thrice this year,” He said to reassure the listener that the name of the city is not synonymous with death. “But what kind of research is that which cannot be done in Abuja, or elsewhere?” I asked again, but now with a lesser degree of worry. “I shall be calling you again to arrange a meeting, so I can brief you further” “Okay, thanks” I answered feeling relieved a harbinger of death had gone.

I immediately began thinking of possible excuses to give at the proposed meeting. And for survival sake, they came aplenty. “Bring on the meeting” I soliloquized, “I have multiple reasons to decline!” Coincidentally the invitation to Maiduguri reminded me of the time three, or so years ago, that I was to begin an assignment as a Visiting Professor of Communication and Multi-Media Design at the American University of Nigeria (AUN), Yola. In that year, the menace of Boko Haram was still fierce, forceful, and frightening. Virtually all those I told kicked against travelling to Yola for any reason. They argued that it could hardly be a safe place to be because of the frolics of rampaging insurgents. Somehow, I found a strong reason to resume, and indeed completed my tenure without hearing the sound of gun around Yola (That was then though). The heavy presence of military personnel in places sometimes however signaled the place as war-torn environment.

After the meeting with my caller, I now also found a strong reason to try out Maiduguri. On arrival, it was a bit easy to read that I was new in the city, tried as I did to conceal it. A co-passenger had told me on alighting from the plane that he feels safer in Maiduguri than Abuja. I knew he only wanted to give some assurance of safety because I had a thousand and one reasons to counter him. There was however no need for the debate. I thanked him for his confidence-boosting statement and moved on.

A taxi beckoned on me, and my colleague, asking where we were headed. “We are going to XYZ Hotel” I responded. “Okay let’s go sir” “But I hope you are not going to take us to Boko Haram oooh”, I asked between a joke, and a quest for a reassurance “No, not at all. I know all these drivers here. They are all simply doing their jobs. Please feel free to join him. He will drop you” The passenger who earlier reassured me while alighting from the aircraft had overheard me, and responded. We all smiled and departed the Airport thereafter.

As the driver drove off, stopping at one, two, or three checkpoints, and at traffics, before the hotel, I pretended to be at alert, preparing to hop off the car, and sprint, just in case. Everyone in sight was thought to be a potential attacker, a Boko Haram member, and therefore I should “be prepared” like the Boy scouts motto. Again, thoughts of bomb ripping off somewhere (God forbid) spiced those needless fears. Through the surprisingly well-paved, beautiful, and well-lit roads, we meandered. Amidst many seemingly calm looking and resourceful residents, we eventually arrived the quiet hotel vicinity. As it was at the Airport, in sight were many foreign workers at the Hotel. “If Oyibo (white) people can be this much in this city, then why are we afraid?” my colleague asked, while I wondered if he was actually expecting an answer from me. Eventually though, we settled down, and work began in earnest.

Maiduguri had hitherto being remembered for a range of reasons. First, I always recall it as a distant city, tucked at the tip of Nigeria’s far eastern flank. The weather is often hot and dry, with flies finding the place a good habitation. The earth of the city is Sahelian: dry, dusty, and shifty. When it rains, the grounds labour to soak in the rainwater, eventually creating marshlands, and unsightly driveways. The city has a good share of the Nigerian rich. Their palaces, cars, and their security easily distinguish them. The palaces are imperial, lavish and luxurious. The cars are exotic, sleekly, and presidential. The Mosques in the homes of the rich are often conspicuous, probably to reflect a degree of piety. The city is historic with the rich heritage of the Kanem Borno Empire. The El-Kanemi of Borno, and the Shehu of Borno are legacies of an illustrious past. Capital of Borno State, Maiduguri has produced many Nigerian greats like Alhaji Waziri Ibrahim, Shettima Ali Monguno, Sir Kashim Imam, and a legion of others. The story of Maiduguri and the enveloping Borno State however changed forever with the birth of Boko Haram.

You hardly would want to hear first-hand stories of Boko Haram activities from witnesses to the crisis. Where do we start? Do you want to hear about how people have practically exited the villages, and have obviously cramped into Maiduguri in search of safety, and security? Or would you rather want to hear of tales of herculean multiple security checks, and counter checks in the heat of the crisis? Are the stories of mothers abandoning their children, so they could move faster from death, or the sorry tales of maiming that populate the streets and the hospitals expected to be interesting? Shall we rather talk about how people were life witnesses to the death of relatives, friends, and family members on the slaughter slabs of the insurgents? Perhaps we should leave all that and talk about how unusual the insurgents can be, by being fierce, fiendish, and eschatological? Could we be talking about how resident sense of security is assured until they lose that sense through instant death? It is doubtful if the entire dimensions of the crisis can be covered even in a long time to come.

But see: The mindset of the insurgent is terminal. Death, that five-letter word, which man innately desires to prolong for as long as possible is uniquely not feared by the fighters. They dare death now and again. Thoughts of it mean nothing to them. While the average man wants to live for as long as possible, the insurgent cares not-he wants his desires satisfied, and definitely ready to die pursuing it. With arms in hand, and walking in dangerous paths, and always ready to provoke the legitimately armed state operative, the insurgent powers on, and confounding the imagination of the regular citizen. That citizen looks on, almost gripped, but believing in the protective ability of the military.

The military is nevertheless also human but differentiated by training and ammunition. He is probably not bogged down by the fear of death; otherwise, his job would not be done. He dares, defends, and dares again, defending yet again, so the citizen can sleep. He might die in the process, as many have done, or just get injured, if luckier, like many more have. It is all seen as a price, an ultimate prize to protect a fatherland. It is the reason why the military deserve great respect. But for them, we would have been overrun. It is okay to say it is their job, but we should not lose sight of the maximum danger always on the path of the soldier. It can be worse where the enemy is a gorilla, or when the battle is asymmetrical. Not sure the kind of curriculum available for this sort of battle in the military academy, but the characteristical element of surprise, or ambush, or hit and run in asymmetrical warfare can be devastating, if not problematic to deal with.

Nevertheless, it must also be said that Boko Haram is a result of the failure of society. It is a manifestation of some deep-seated cankerworm, which took ages to gestate, to mutate, now exploding beyond control. Do you want to call it uncontrolled birth, or hopelessness, or doctrinaire believes in a post-life bliss? Should it be attributed to poverty, deprivation, and depravation, or long years of neglect of a malaise by government? Point however that is the insurgents are not products from the sky. They grew from a system. And dealing with the violent emotion would include dealing with the ruined system. Not all hopes are lost however. There are still plenty rooms for corrections. In the meantime, may God be with the military. As was, is now, as ever shall not.

Dr. Adeniyi is head of the department of mass communication, Baze University, Abuja.