BY JONAH IBIAMAGABARA

In my previous article, I talked about hope on the horizon regarding the rebirth of Nigeria and I got a fair tackle from some persons who have become desperately pessimistic about the prospects of Nigeria. But whereas I remain adamant that Nigeria is changing, I acknowledge that the change is seemingly too slow for many reliably disappointed Nigerians and that one of the chains unwilling to allow Nigeria to attain its full degrees of freedom is the famous quota system, which has become a principal demon fashioned against Nigeria.

First, we go back to a discussion I had with a colleague sometime around 2021. As I pointed out the unfairness in better qualified persons losing educational and work opportunities simply because they come from states with seemingly more intelligent (academically) persons, he argued that the “best” candidates from the low performing states also deserve an opportunity because if the country were to go strictly by merit, certain states would not be represented in many aspects of the society.

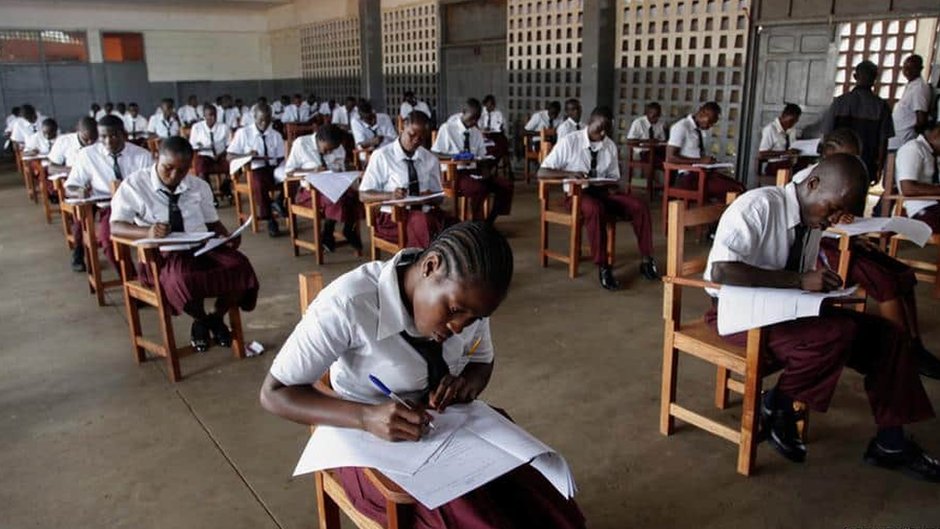

While this argument would appear to have some validity, it does not address why some states do not seem able to ever compete with other states on academic attainment. If we argue correctly that intelligence is not based on ethnicity, then we ought to be worried that a part of the country consistently outranks another part whenever exams are written.

Advertisement

Second, we go to another discussion I had with another colleague who bitterly complained that Nigeria can never develop as long as the quota system remains in place. This person pointed out, anecdotally, to persons with arguably less intellectual acumen who managed to get employed at the same time with him and somehow rose into senior management. The complainant has given up on ever seeing his country become better and had sent his family abroad while staying back to milk whatever he can from Nigeria.

Unfortunately, a good percentage of Nigerians fall in this category of persons who do not see anything changing because of deep resentment about the impact of the quota system on national development, and so they merely exist within Nigeria as domestic mercenaries forced to see Nigeria as not worth having hope in.

We may want to argue that the architects of the quota system or federal character had somewhat good intentions. However, if after more than four decades of applying quotas, we still cannot have states at par, then we should tell ourselves the truth because we can only wake someone who is asleep, not someone who is pretending to sleep.

Advertisement

Just like the central distribution of national income which makes most Nigerian states to be mere administrative centres unfit for independent existence, the quota system makes the so-called educationally less developed states to remain intellectually lazy and unwilling to prioritise formal education. In fact, without the benefit of rigorous scientific data, one can opine that there is a correlation between the quota system and the large number of out-of-school children in Nigeria.

The thesis is quite simple. If we know that we can get the same opportunity as others while scoring less than 20% of their score in some instances, what would be the motivation for working hard to become more competitive? Why should the state government in Yobe or Zamfara invest massively in education if their people can get into schools and public institutions with the current level of underperformance? There is simply no incentive!

Similarly, a low-scoring individual who got a position based on quota is less likely to have the required grit to work as hard as his or her higher scoring peers, and even when motivated, may retain the disadvantage of a lower intellectual capacity.

So, how do we go from here? We first have to acknowledge that the quotas do not work in bringing the best minds to develop the nation. But we do not have to simply turn the lever to the other side and say that effectively immediately we would stick to merit across board. Sometime ago, I proposed a sliding scale to address the resource control question.

Advertisement

I think the same thing can apply to the quota system. We can draw a line in the sand and give all states ten years to prepare for the removal of quotas. For example, in Year 1, 10% of available opportunities that are currently reserved for quota-based distribution would be allocated to the best performing candidates (merit) regardless of what state they come from, while 90% is retained for quota-based distribution. In Year 2, the merit pool increases to 20%, such that by Year 9, only 10% of opportunities are reserved for quotas to make allowance for some token representation.

It is said that the best time to plant a tree was twenty years ago and the next best time is today. We have lost 65 years to the shackles of quota-based distribution and achieved dysfunction. But if we turn the tide today, in less than ten years’ time, an average child in Zamfara would be able to compete with his or her peer from Anambra. Remove the bad incentive of assured quotas and see states begin to invest in enhancing their educational systems and our human development indicators would improve all around Nigeria.

Notes

-

This article focuses on “average” performance across states and does not claim that a state with mostly low performers cannot have its best performers able to match their peers from other states.

Advertisement -

In admissions into universities and unity colleges, there is already a provision for some intakes on merit. The proposal in the article applies to the provision currently reserved for quota-based distribution for admissions and public sector jobs.

-

More insights on the quota and federal character system can be found here, here, here, and here.

Advertisement

Jonah Ibiamagabara can be contacted via [email protected]

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.