BY ZUHUMNAN DAPEL

Two eminent Nigerian economists, along with some notable politicians, recently claimed that the Nigerian economy is stable and therefore heading in the right direction. Their definition of stability is based on the observed behaviour of inflation (the rate at which general prices rise), the exchange rate (the value of the local currency compared to the US dollar), and the cost of borrowing or interest rates.

In their view, if these variables are not rising and falling at an alarming rate, the economy can be regarded as steady. However, their notion is violated by ample evidence.

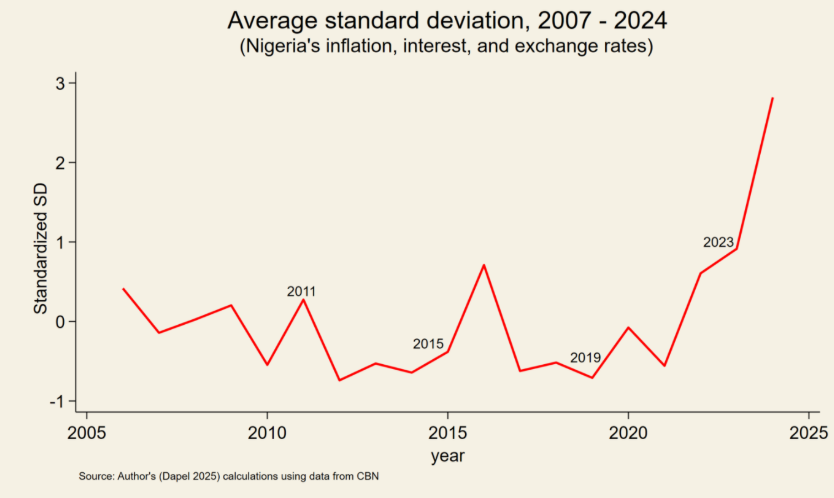

Available data, even through the lens of their theory, refutes their claim that the Nigerian economy is sturdy. The chart below shows that Nigeria experienced its most pronounced economic instability in 2024—the worst in nearly twenty years.

Advertisement

There were fluctuations in Nigeria’s economic stability from 2007, reaching its highest level as recently as last year. The general election years (2011, 2015, 2019, and 2023) experienced notable spikes, indicating turbulent periods in Nigeria’s economy. The red line decreases when the economy is more stable – calmer, with fewer surprises in inflation, interest, and exchange rates.

The chart illustrates the instability and unpredictability of Nigeria’s economy over time, using the three key indicators. The standard deviation shows whether these indicators were steady or all over the place. The red line goes up when inflation, interest rates, and exchange rates are more unstable. If prices, interest rates, and currency values remain relatively stable, the line is low — that means stability.

If they change significantly, the line rises — that means volatility or instability. A caveat: the word “stable” in the title of the article is in quotation marks (or parentheses) to suggest that the stability being referenced might not be entirely genuine or straightforward. It’s a way of indicating it appears stable on paper, but there’s more to the story.

Advertisement

Happiness is at risk when economic fortunes are under threat.

Gone are the happy days? In 2003, New Scientist Magazine published a report that graded Nigerians as the happiest people on the planet. However, two decades later, the bliss level has sharply declined to 105th: out of 147 countries in 2025, according to the World Happiness Report, coinciding with the period of growing insecurity and worsening economic conditions for the majority of households in the country. For instance, between 2003 and 2025, food inflation increased by nearly 300per cent without a corresponding rise in farmers’ incomes.

In 2019, over 70per cent of Nigerians allocated more than half of their total household expenditure to food, at a time when food inflation hovered around 15per cent. By June 2025, food inflation has climbed to approximately 22per cent. With no recent household survey data for 2024/25, we can only speculate on the depth of hardship this inflationary pressure has imposed—likely pushing millions further into food poverty, especially among already vulnerable populations.

This trajectory demands bold and targeted interventions—from revitalising domestic food production systems to raising the real incomes of the bottom 75per cent of the population. Without such measures, the affordability crisis will continue to erode nutritional security and economic resilience.

Advertisement

Should we blame the reforms?

In recent years, Nigeria has implemented a series of bold economic reforms aimed at stabilising the economy and attracting investment. However, only two of these reforms have had a direct and widespread impact on the daily lives of Nigerians: the removal of petrol subsidies and the floating of the exchange rate.

The decision to float the naira led to a dramatic surge in the dollar exchange rate, rising by over 100per cent, making imported goods and services significantly more expensive. Simultaneously, the removal of fuel subsidies led to petrol pump prices skyrocketing by more than 300per cent, triggering a sharp rise in transportation costs and business operating expenses. Together, these measures have driven up the cost of living, placing additional strain on households and businesses already navigating economic uncertainty. This is because the price at the pump is linked to the prices of hundreds of other commodities on the streets of Nigeria.

Advertisement

While many Nigerians support ending the subsidy regime—widely seen as a breeding ground for corruption in the oil sector—they remain opposed to the steep increase in pump prices. Critics argue that it is possible to eliminate subsidies without inflicting such economic pain. One proposed solution is the adoption of a robust regulatory framework, similar to the UK’s Ofgem model, which ensures that energy companies earn only efficient profits rather than excessive monopoly gains.

The desperate need for a growth miracle

Advertisement

Economic growth is widely regarded as one of the most effective ways to lift people out of poverty. I am referring to inclusive growth, where every member of society is given a fair opportunity to contribute to this growth and earn a living as a result. However, Nigeria’s growth-poverty relationship is mixed.

Between 1985 and 1992, Nigeria’s economy expanded during the structural adjustment program. The average living standard of Nigerian households rose by more than 26 per cent relative to 1985, while the average living standard of the poor increased by a very small margin, just over 1 per cent. This is because the growth came with a rise in the level of inequality; the gap between the rich and everyone else (measured by the Gini index) widened by 16 per cent.

Advertisement

Moreover, the poorest of the poor, or the bottom 23 per cent, saw a significant decline in their average living standard. The upper middle class gained more than the poor but less than the richest 15 per cent.

Based on the analysis of the data, rising inequality in Nigeria between 1985 and 1992 prevented nearly seven million of the country’s poor from escaping poverty. In addition to inherent state constraints, they were ill-prepared to take advantage of opportunities provided by growth, as most lacked the labour market skills in demand. In other words, inequality disadvantaged the poor regarding opportunity growth.

Advertisement

Although half a loaf is better than none, this is not the kind of growth Nigeria desperately needs. The country requires trickle-down or inclusive growth—growth that benefits everyone. Nigeria was once at this point.

The growth period, from 1996 to 2004, tells a different story. Nigeria experienced a notable shift in its economic landscape, marked by rising living standards among the poor and a reduction in income inequality. During this period, the share of total income held by the poorest segments of the population increased, enabling approximately 13 million Nigerians to escape poverty.

This era of progress coincided with several transformative national developments. The return to democratic governance in 1999 ushered in a wave of optimism and reform, while sweeping changes in the banking and telecommunications sectors spurred economic activity. Additionally, increases in nominal public sector wages and pensions contributed to improved household incomes.

To learn from the past, Nigerian policymakers should consider two key questions: Why did the first period of economic growth benefit the poor less than the second? And how can future growth be made more inclusive? Evidence suggests that when economic growth is accompanied by a decline in inequality, it results in greater reductions in poverty compared to when inequality increases.

While the conditions that drove growth between 1996 and 2004 may differ from today’s context, and replicating past strategies may not guarantee the same outcomes, it’s still worth exploring those approaches to inform future policy.

To generate such growth, a collaborative effort between the private sector and the government is needed. The government should focus on providing vital infrastructure—such as energy, railroads, highways, and security—as well as establishing effective institutions.

Meanwhile, the private sector can contribute to investments and production. Good infrastructure lowers the average cost of doing business, making the economic environment more attractive to foreign and local investments and ultimately creating jobs.

Although the economy has experienced periods of growth, it lacks the momentum and inclusivity needed to lift a significant portion of the population out of poverty.

An academic study titled “Will the Poor in Nigeria Escape Poverty in Their Lifetime?” has revealed a troubling outlook for millions of Nigerians: more than 70 per cent of the population is at risk of spending the rest of their lives below the poverty line if the country’s economy continues to grow at its current and historical rate. The study highlights a critical issue in Nigeria’s development trajectory: while the economy has experienced periods of growth, it lacks the momentum and inclusivity necessary to lift a significant portion of the population out of poverty. Therefore, without a substantial shift in economic policy and growth strategy, Nigeria risks entrenching poverty for decades to come.

Zuhumnan Dapel can be contacted via [email protected] and on Twitter at dapelzg

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.