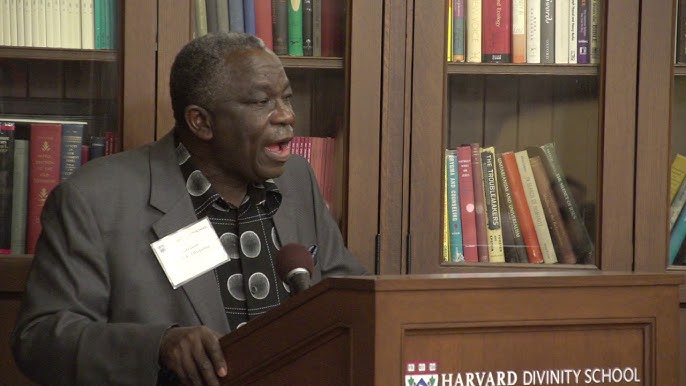

I met Professor Jacob Olupona on the Board of Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba, Ondo State. Then, he often travelled down from Harvard University for the Board meetings and always seemed in a hurry to go back. He is profoundly deep and introspective; it is no surprise that he is a professor and a member of the faculty at one of the world’s most prestigious universities. I also noticed that Olupona is folksy. I found that he relished in breaking down complex concepts and reassembling them in a way that would make even a moron grasp his gist. He is like Neil deGrasse Tyson, the African-American astrophysicist who often makes space science seem like a piece of cake.

I further noted that the professor of comparative religion is a consummate storyteller and has a knack for making the esoteric seem normal. He also, like consummate storytellers, has a way with words. I hadn’t read any of Olupona’s books before we met in 2014. I only heard about ‘The City of 201 gods,’ his book on Ile-Ife and its assorted pantheons, from Professor Sophie Oluwole (God rest her soul) cryptic critique on the work. Later, I read ‘In my Father’s Parsonages,’ a biography that Olupona did on his father, Rev. Michael Olupona, the vicar at St. Peter’s Anglican Church, Ile-Oluji, from 1957-1966. The book struck a personal chord with its vivid description of my hometown, Ile-Oluji, in the 1960s, awakening nostalgia for some events that shaped my youth. ‘In my Father’s Parsonages’ also offers a clear vision of Reverend Michael Olupona’s personality, the vicar whose cursive handwriting has adorned my infant baptismal certificate from 1963.

I loved listening to the professor’s perspectives on global politics, especially on race and identity politics from his perch in Harvard. One afternoon at the lunch table in Akungba, the topic hovered on African medicine after the board meeting. ‘Of course, indigenous methods were here before the so-called Big Pharma,’ Olupona said as a matter of fact, ’why are we reticent about the fact, unlike China or Korea?’ But he wasn’t done yet: ‘we ought to at least start to debrief the dying generation of indigenous healers, start interrogating their life-beliefs and therapies.’

I thought those were rhetorical postulations until Olupona intercepted me later in the day to ask if Baba Loogo, the foremost traditional healer in Ile-Oluji, was still alive, if he would acquiesce to a documentation of his life and some of his therapies. The son of the vicar, who has charted a career by researching temples, shrines, and indigenous sanctuaries across the world, had his early life in Ile-Oluji. He attended St. Peter’s Primary School and Gboluji Grammar School, from where he proceeded to the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. He was familiar with Ile-Oluji and Baba Loogo, a renowned medicine man, whom he wanted to document. He would later tell me stories of his numerous escapes from the walls of the vicarage to watch the medicine man perform in town during the Ogun Festival in his youth. The habit followed him to the boarding house at Gboluji Grammar School, where he used to jump the fence to feed his curiosity.

Advertisement

The discussion at the lunch table in Akungba and the professor’s insistence culminated in ‘In the Twilight of Time – a Biography of an African Medicine Man,’ a 262-page book on Baba Loogo, h e co-authored with this writer. It had set out to chronicle the thoughts of the aged medicine man, compile his methods and therapies. But the book, published by University Press PLC in 2024, has only achieved the first objective. We were en route to attaining the latter when Baba Loogo died recently in his sleep at Ile-Olujl.

Loogo insisted he was 104 years old when I first met him at his house in November 2021. I didn’t arrive that November morning expecting an interview, but to broach the book project. I had carefully honed my pitch for the meeting, aware that time was short, eternity might be beckoning to the centenarian, and there might be no other opportunity for a re-run. I also recall ruminating on the possibilities: What if the man refused to play ball and shut me up? If he agreed, would he still have the mental acuity to recollect activities from the vital years that carved his niche as a healer? How much could a centenarian recall anyway, how much would he be capable of rendering in a precise, logical sequence?

A thousand other thoughts assailed, pricking at my nape as I climbed the wooden stairs to his parlor on that first visit. I considered the possible hue of the prospective readers. The book might spark interest in the Western world, particularly in intellectual circles, Olupona’s primary constituency. What about here, where books, especially those on indigenous methods, are typically scorned or draped in apocalyptic garb? History here often lies deeply buried away from sight especially if it is about the mores and thoughts of our forebears. That November morning, the Voltaire lines on the profoundness of written words haunted as I climbed Baba Loogo’s wooden steps: ‘You despise books, you whose lives are absorbed in the vanities of ambition, the pursuit of pleasure, or indolence, but remember, all the known world—excepting only savage nations—is governed by books.’ I thought that 18th Century French philosopher would be baffled by the general attitude to books, history and our culture.

Advertisement

But Loogo challenged my assumptions when we met. It was clear that time was kind on him. He stood nearly straight. The six-footer hardly looked his 104 years. The man approached with a lively gait, stretching out a hand that grabbed mine like a giant paw. Upon closer observation, I noticed he was slightly bent. Loogo graciously consented to the business at hand, and agreed to our proposals to write his biography. He granted numerous interviews in the course of the three-year project. His memory, like his gait, belied his age. He was candid. He did not refuse or parry any of our questions. I left the project feeling that there are benefits to chronicling an old man in his twilight years, when his gaze is fixed on eternity. It seems the heart likes to reel unfiltered when mortality beckons.

Baba Loogo took us through his infancy to his adolescence, starting from the 1920s. He steered us from the footpath to his father [Bamutula’s], house at Idi Oma quarters, into the dusty roads of his youth, the complexities of adulthood, the ease and pains of old age. He pontificated about birth, life struggles and death. He talked about Yoruba religion and culture, tradition, and the changing mores in society. Loogo shared how he came to earn the complex reputation of love and fear of the people in this picturesque community. He also spoke about marriage; especially the generational influence of marriage on children, averring that, ‘A wife would treat her husband the way she saw her mother treat her father.’ I thought about that a bit.

The man began learning traditional healing methods from his father as a child. His half-brother, Ajayi, took over in his adolescent years when Bamutula died. ‘I learned about [the uses] of countless herbs; how to identify them by sight, smell and touch. They [Bamutula and Ajayi] often said that my dexterity was beyond my years.’ There were bizarre sides to the trainings too, especially the nocturnal visits of the ‘bodiless beings’ he said often instructed him on how to prepare some remedies: ‘those days I rarely slept, sometimes I would be roused [by the spirits], and directed to do so and so.’ Spiritualization of healing methods, such as Loogo just recounted, has been identified as a major bane of African medicine. When physical therapy is comingled with an unseen spiritual force, it could make empiricism a hard nut to crack. But a project to compile and examine only the physical side of such therapies could unearth many cures that are still unfamiliar to modern medicine.

Loogo did not doubt the efficacy of his methods, He reeled out some contemporary cases of ailments he had successfully cured: The lame child of a famous politician in Nigeria whose parents had given up she would ever walk, the lady bitten by a snake who, ‘Would have died if they had brought her a minute later,’ and the Whiteman ‘that couldn’t get it up despite serial treatments and therapies from conventional hospitals.’ He said the latter was incredulous after the cure. He “returned with his wife, with a slew of gifts, including the set of embroidered sofa you saw in [my] balcony.”

Advertisement

Baba Loogo eventually agreed to compile his herbal therapies for study after the publication of his biography, ‘In the Twilight of Time – a Biography of an African Medicine Man.’ The project already started when the man died in his sleep on June 15, 2025. According to the family, he was aged 108 years old.

Akinyosoye is on the faculty of GSCL, Oil & Gas Consulting Group, Abuja

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.