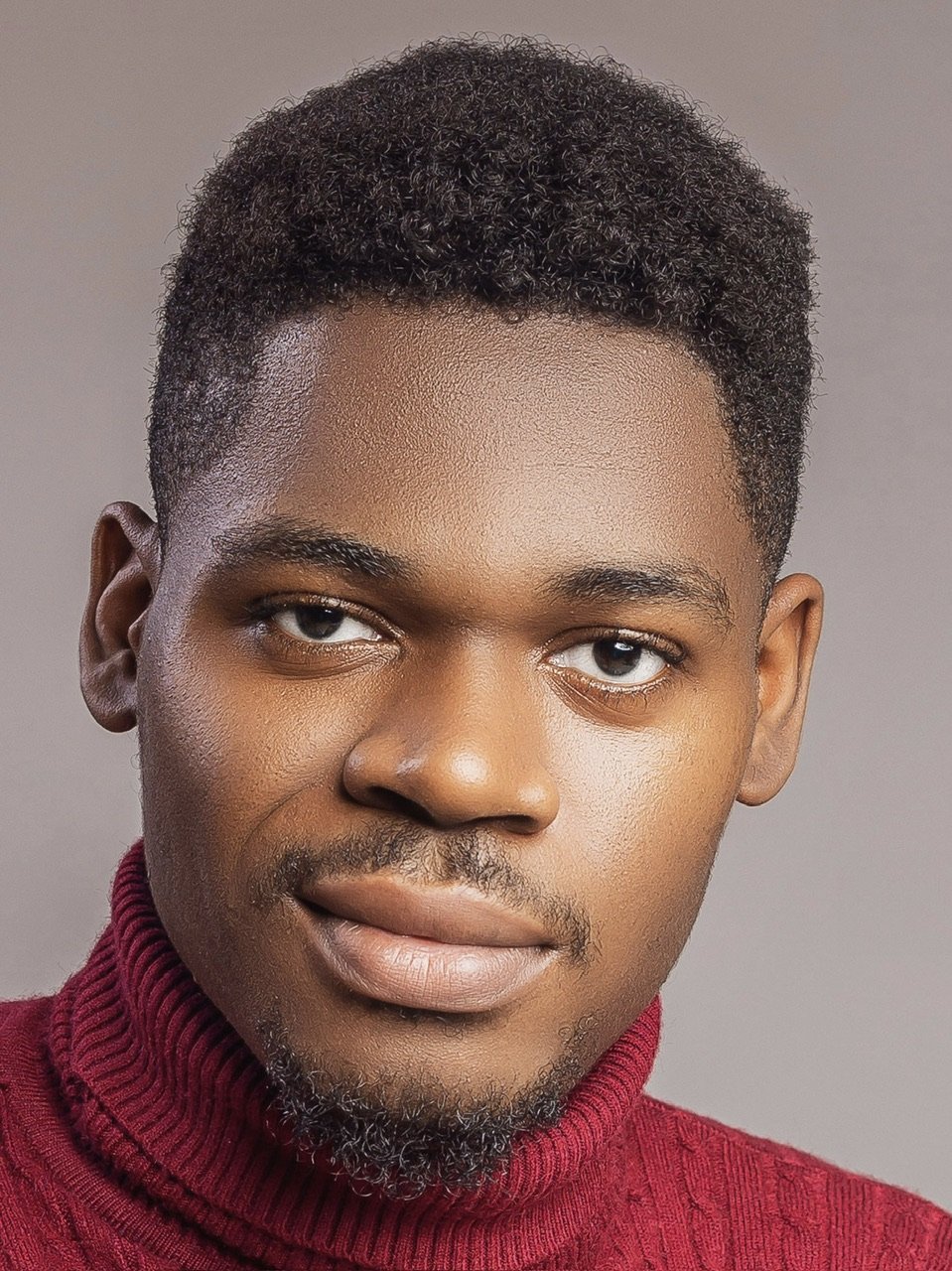

The cover art of Akin Adesokan's novel 'South Side'

The most archetypal life of the stateless African, marked by identity conflict and forced displacement, is at the core of Akin Adesokan’s second novel, South Side.

The defining internal conflict of South Side’s central character, Abel Dankor, an accomplished novelist in his mid-30s, condemned to a life of constant migration while pursuing naturalisation in the fictional West African state of Mande, is a compelling demonstration of this dilemma.

Born in the late 1930s on international waters, leagues northwest of the Gulf of Aden, to immigrant parents fleeing victimisation in Mogadishu, Somalia, Dankor’s statelessness warranted familial itinerancy so pronounced, he had lived in 15 different countries by age 19.

His status as a novelist also bequeathed an unnatural globetrotting that sees the novel further spotlight the themes of colonialism, migration, political instability, and Eurocentrism affecting African countries.

Advertisement

In this light, South Side opens with Abel Dankor reading a rather deprecating newspaper description of a power-besotted and entitled military ruler enthroned by coup, yet divisive with bogus claims of having ancestral links to a pre-colonial kingdom that once sat in the place of what is modern-day Sierra Leone.

The book then proceeds to explore this character’s backstory, drifting from an uncertain beginning as a teenage refugee student in 1950s UK to his becoming the love-smitten author of five acclaimed books.

The murder of his mentor, a poet who was to sponsor his naturalisation, in the crossfire of a coup leaves Dankor spiralling into melancholy at a US storytelling residency, until his chance meeting with Valeria, an embattled Italian-Australian co-guest whose own past epitomises resilience and offers him motivation.

Advertisement

A signal that Dankor’s childhood friend will occupy a top political office in Mande leaves Dankor at a crossroads, having to choose between companionship with Valeria in Europe or a return to Africa for his pursuit of citizenship in Mande.

South Side’s deliberate slow-burn pacing embraces narrative maximalism that viscerally immerses the reader in Abel Dankor’s world as a reclusive, socially conscious, and apolitical creative writer.

The interiority of the central character is crafted in painstaking detail with a first-person narrative point of view and in the simple past tense.

The story’s plotting is non-linear, going from the character’s present, where he is rummaging through library archives for book research in DC, to the past that ushers the readers into his backstory, and then onward to a series of defining events that succeed the character’s present.

Advertisement

The sociology of South Side’s flat characters leans into effusive narration that arguably risks alienating the non-cerebral reader inclined to “feel-good” literature. Whether or not this is an element of style, it makes the novel a slightly passive concatenation of events chronicling the nuances of a writing career.

A clear-cut build-up of dramatic character arc is less pronounced in South Side, making it read almost like a memoir to depict what is described in literary criticism as the “poetics of engaged expatriation”.

South Side’s active timespan is set between the mid-1950s and the mid-1970s.

The book is brilliantly steeped in sociopolitics, still very much relevant to contemporary African affairs, bringing a convincing context to its fictional worldbuilding.

Advertisement

The most pronounced theme in South Side is the topical crisis of statelessness in Africa.

To be stateless is to find oneself belonging everywhere and nowhere at once, either by the accident of history, gaps in law, or the cruelty of politics. It is to be born in communities blurred by colonial nuances, dislodged by conflict, or denied citizenship due to ethnicity, gender, or lineage. Unable to claim the rights reserved for legal nationality, this means being subjected to perpetual refuge seeking, sometimes denied access to education, health care, decent employment, or even the dignity of official recognition.

Advertisement

In West and Central Africa, nearly 1 million people are estimated to be stateless as of mid-2025, within a broader group of 12.7 million “displaced or stateless” individuals.

Many African countries are still signing or ratifying the 1954 and 1961 Statelessness Conventions, and the African Union adopted a protocol in 2024 to address statelessness continent-wide.

Advertisement

There are growing domestic reforms seeking to allow women-to-children passage of nationality.

But low birth-registration rates, especially among nomadic, indigenous, or displaced communities, mean many children still grow up undocumented and invisible.

Advertisement

The UN refugee agency, in response, says most African states need robust legal safeguards to guarantee nationality to children born in their territory who would otherwise be stateless.

This is where South Side comes in. It is a timely platforming and humanisation of this pertinent crisis.

South Side is a book for socially conscious readers interested in a nuanced exploration of what it means to belong or not belong, both on an individual level through the main character’s internal search for identity and on a continental level in how post-colonial Africa’s political realities complicate that search.

Published by Regium, an imprint of Parrésia, South Side hit the shelves in mid-2025.

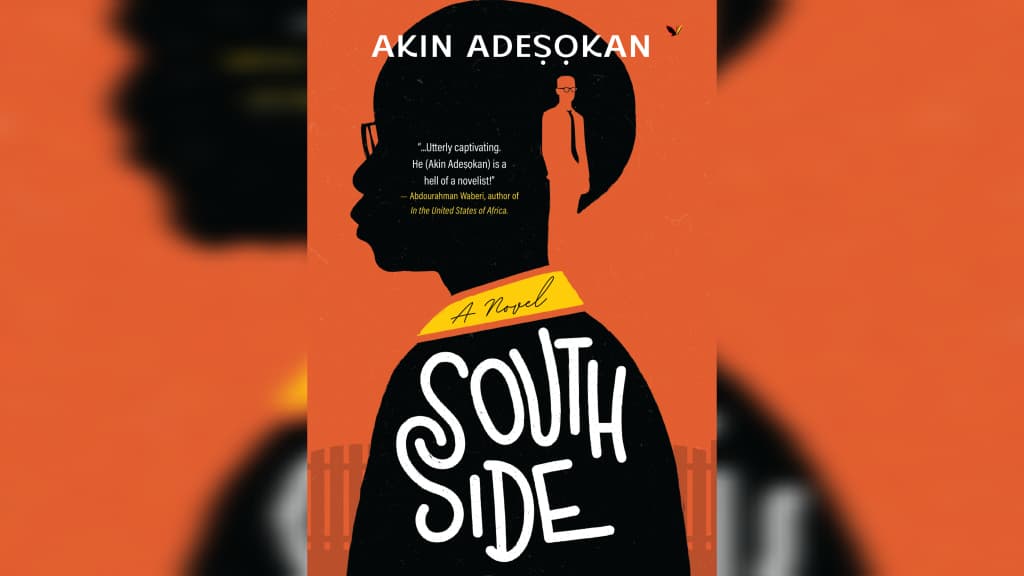

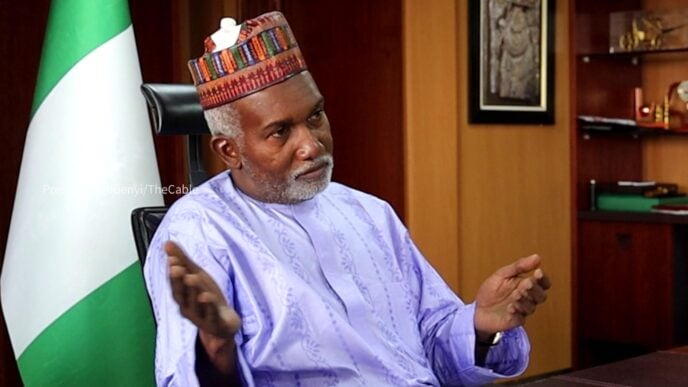

After reading the book, I spoke with its award-winning author, Akin Adesokan, a US-based Nigerian professor of literature whose critically acclaimed first novel, ‘Roots in Sky’, was published in 2004.

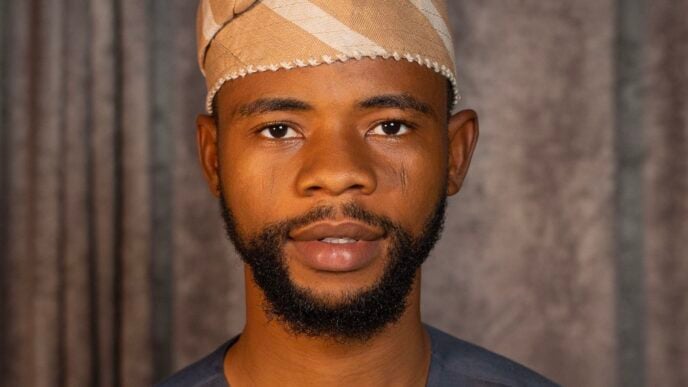

Stephen Kenechi: Abel’s journey highlights the profound challenge of being stateless. In contemporary Africa, with conflicts and fluid borders, what do you see as the most pressing issues for stateless folks, and what role do you believe literature can play in raising awareness or advocating change?

Akin Adesokan: The most immediate issue is the same as confronts the protagonist in South Side, that is, the desire to find a home, country, or nation to which to belong. That’s on the individual level. However, coming from an African country where most people take nationality for granted, I think that the most imaginative thing to do for those who control these things, granting rights of citizenship and those sorts of things, the most ethical thing to do will be to make a given African country home to any African living on the continent, or aspiring to do so from any part of our known world, as long as such a person desires it. There are thousands, maybe millions, of people on the continent, refugees, internal migrants, who have nowhere to go. In my view, it is politically shortsighted to draw a line on the map and make it inviolable, especially for those who don’t have a choice, the most vulnerable members of our societies. There’s, of course, a logic to national boundaries. Otherwise, what I’m suggesting wouldn’t make sense. My main point is that in the world envisioned in the novel, no human being, African least of all, would be considered an alien in any African country. My artistic vision extends this idea to the rest of the world without exception.

Stephen Kenechi: Your novel touches on the difficulties and irony of an African finding it harder to access other African countries than Europeans. Given ongoing discussions and initiatives like the AfCFTA and the AU’s push for free movement, what are your thoughts on current realities and prospects of intra-African travel and migration?

Akin Adesokan: African governments are working on visa-free entry for citizens of other African countries. This is small progress and quite commendable, I think. I hope that these initiatives are sustained and that the bureaucrats go further, go beyond acts of grace or economic calculation, as individual government policies in Kenya or Lesotho. Africans are lucky in one important sense: the more progressive among an early generation of the continent’s leaders and thinkers, like Kwame Nkrumah, Cheikh Anta Diop, and Patrice Lumumba, had an inclusive vision of the entire continent as one united space. That vision is now buried, maybe forgotten, but there are those with strong memories of it. If I were to write a sequel to South Side, I would make Abel return to Mande on the condition that the new government implement just that sort of plan. After all, the country is now being ruled by those he knew and trusted, if Abel can trust anyone involved in politics (laughs).

Stephen Kenechi: The recurring theme of coups and political victimisation is central to South Side. How do you believe the experiences of characters like Sir Koroma, Yacouba, Jilo, Fabio, Wande, and Abel himself reflect the long-term impact of political volatility on individuals, families, and dissidents in contemporary African nations?

Akin Adesokan: Let’s keep in mind that the active timespan in the novel is the mid-1950s to the mid-1970s, and so the phenomenon of military rule is of priority as the protagonist, Abel, and his closest friends—everyone that you mentioned—try to find an emotional balance between their personal needs and commitments to the safety of everyone in society. Military rule has pulled African countries back in so many ways. It’s had a violent impact on people and the physical environment, and we haven’t even begun to take a proper measure of what those are. Military rule is essentially a group of people holding guns to the citizens’ heads daily. It’s not a fun way to contemplate living, and our guide in this is a fiercely independent writer.

Stephen Kenechi: Abel’s criticisms in chapter nine about the Western framing of African stories are profound. How do you navigate the complexities of presenting nuanced African narratives to a global audience, and what responsibility do you feel contemporary African writers have in challenging or reshaping prevailing perceptions?

Akin Adesokan: Thank you for this question. There is no simple answer to the question, it’s been around for a long time, because modern African writers, Caribbean writers, and Latin American writers, to a lesser extent, all started out looking toward European and American centres as places to excel, to gain international visibility. That set the standards in a major way, and expectations followed from that, on all sides. But I don’t think it’s helpful to prescribe responsibilities to writers and other creative people. People make art out of their experiences and personal sensibilities, preferences, or what have you. In any aspect of life, the golden injunction is to know yourself. Once you have that figured out, hopefully early in your personal journey, the rest is relatively easy to manage. It helps if you’re lucky, too, but one has to have the sensibility to recognise that luck. A creative work—a book, a film, whatever—exists to the extent that it finds companionship in the imaginary of another, and that other person could be an editor, a publisher, or a supportive reader. All of my writings have been made to exist by people who have felt the necessary fire to bring them to life. It is gratifying that Azafi Ọmọluabi and Parrésia took a chance on South Side. I know what some African and Black writers go through to find acceptance within certain publishing parameters, and I know of many non-African writers and artists, including white American writers, who still have difficulties getting their work out. This goes on all the time. At the same time, I don’t want to minimize the importance of willful choice because just as a given African head of state, say Nkrumah again, could positively and deliberately imagine a cohesive Africanness, whatever it might turn out to be, publishers of books, films, music, can creatively develop and strengthen intellectual outlooks that are not beholden to the whims of uninformed or myopic culture brokers, black or white or brown, irrespective of location. It is probably easier in the area of cultural self-empowerment than in the political arena, but there are still serious shortcomings. As a matter of personal observation, I see some of the new African publishers and curators as carrying on with many of the exclusionary practices we often criticise in Western publishers. We can’t be romantic about this at all.

Stephen Kenechi: Jilo’s character, blending traditional spiritualism with modern medical practice, offers a unique perspective. How deliberately did you craft her to challenge simplified notions of “superstitious beliefs” versus “western modernity” in Africa? Do you see her approach as a model for navigating cultural identity today?

Akin Adesokan: Great question! It may sound odd for a novelist to have a favourite among the characters in his novel, but Jilo comes close to that in South Side. Any careful reader can tell! To me, she represents the beginnings of a sensibility that cuts through simple divisions between superstition and its supposed opposite, and I’m very sorry to have made the authorial decision to end her life about halfway through the novel. I have good reasons for that decision in terms of narrative pace—I don’t want Abel to break her heart, and I know that the story must continue beyond the moment of her illness. Jilo has what seems to me to be the best values for her time and place. She’s a medical doctor, which means that she’s committed to modern techniques, those ever-present aspects of life that keep societies going, more or less, and of course, she is invested in the present. I got the idea for her illness, the tuberculosis, from an unusual source, about the life of a political activist in nineteenth century England! Only the illness, though; everything else is locally sourced. What a novel does with a character like Jilo is to suggest a model, an outlook, that provokes thought and fires the imagination, that refuses easy answers, and I appreciate your thoughtfulness in seeing that character as I imagined it.

Stephen Kenechi: South Side employs a “slow-burn” pace with deep dives into Abel’s interiority and extensive backstories. You’ve been profiled as employing what is described as the “poetics of engaged expatriation”. How did you determine the balance between narrative flow and the detailed exploration of Abel’s consciousness, perspectives, and past, especially given his constantly shifting physical locations?

Akin Adesokan: I make a decision early in the writing to have the story unfold from Abel’s point of view. In a sense, you could say that South Side is a memoir, a partial account of his life, such as it is. The option is for a narrative style that doesn’t give up on either the worldly or localised aspects of the protagonist’s experience, because after all, he inhabits all of those aspects. That’s another way of turning “poetics of engaged expatriation” into a living thing. There’s a key to this narrative choice in the final chapter, and I hope that readers will find that key, which unlocks pretty much everything else. The story needs to be told novelistically, of course, but in the main, it is a narrative of a series of events that have shaped an individual’s life, with statelessness as the thematic undercurrent.

Stephen Kenechi: Abel’s astonishing number of migrations by a young age might strike a reader as perhaps “unbelievable”. Was this extreme itinerancy intended to emphasise a particular aspect of the migrant experience, or to serve a broader symbolic purpose regarding the displacement of African intellectuals?

Akin Adesokan: Actually, a young person living in so many places within such a short life span is neither unusual nor unbelievable. If we consider its opposite, for example, the itineraries of a diplomat’s child, we see it as a simple though overlooked inversion of privilege. Several years ago, I interacted with a scholar whose boyfriend came from a family of diplomats, and most of the values we attach to nationality, to patriotism, those things didn’t make sense to him. He didn’t take them for granted; they simply didn’t exist for him. That fascinated me a great deal. In the novel, I want to be able to think through such a mindset, because it is a mindset, but from the position of someone privileged, just like my colleague’s boyfriend, who is pushed to recognise the privileges. Abel’s peripatetic lifestyle does both; he’s from a displaced family without the privilege of permanent citizenship, yet he moves fairly effortlessly from one place to another, which is a privilege. So maybe this is one of the things that draws Abel and Jilo toward each other, since she’s coming to an awareness of her being through complex life choices.

Stephen Kenechi: Some readers might argue that a “clear-cut build-up of conflict or character arc” is less pronounced in South Side than in other novels. Was this a conscious choice to reflect the fragmented and often circular nature of life for individuals grappling with systemic issues like statelessness and political instability, rather than a linear plot?

Akin Adesokan: Yes, it was a conscious choice. The novel form is one of the most flexible genres in the history of literature, so flexible that you can do things in it in so many different ways. South Side is not a novel plotted around a drama. There’s a small drama in it, a family drama, that is, but the narrative canvas would have been stretched beyond its capacity if that drama were to unfold, and Abel’s point of view would have been needlessly overshadowed. That family story is abridged for reasons best known to Abel, and one reader at least has expressed a wish to see a sequel, or Part 2, à la Nollywood!

Stephen Kenechi: Abel’s various romantic relationships span continents and cultures. How do you imagine this diversity contributed to his journey of self-discovery and his understanding of “home”, particularly when juxtaposed with his search for stable citizenship?

Akin Adesokan: This is another thoughtful, thoughtful question. Thank you! As a writer, an African writer who doesn’t think his values as superior or inferior to anyone’s, in total confidence, I see the whole universe as my playground or sphere of existence. And I want to convey that outlook to the reader through Abel’s romantic relationships. Despite or even as a result of his circumscribed aspirations on the level of citizenship.

Stephen Kenechi: On a lighter note, how long did it take to write this novel? What was the timeline?

Akin Adesokan: It took as much time as was necessary because I was busy with other things at the same time. Its earliest iteration was a short story first published in the literary magazine Farafina in 2006. In between, I did many other things, wrote and published other books and stories, began several others, and carried out my charge as a university professor. As William Faulkner once said, the relevant question about an act of creation isn’t how much, how big, or how long, but what it is. The important thing is that South Side now exists in the world.