Nigeria has taken a long-overdue step toward climate accountability by attempting to document oil and gas emissions. But while this marks some progress, alarming gaps in compliance and transparency threaten to undermine the effort.

In 2024, the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI) — the agency tasked with promoting good governance in the oil, gas, and mining sectors — released its 2022–2023 emissions disclosure report.

The data is critical not only for addressing global warming but also for unlocking international climate finance and meeting Nigeria’s Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) — the country’s formal pledge under the Paris Agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 20 percent unconditionally, and up to 47 percent with international support, by 2030.

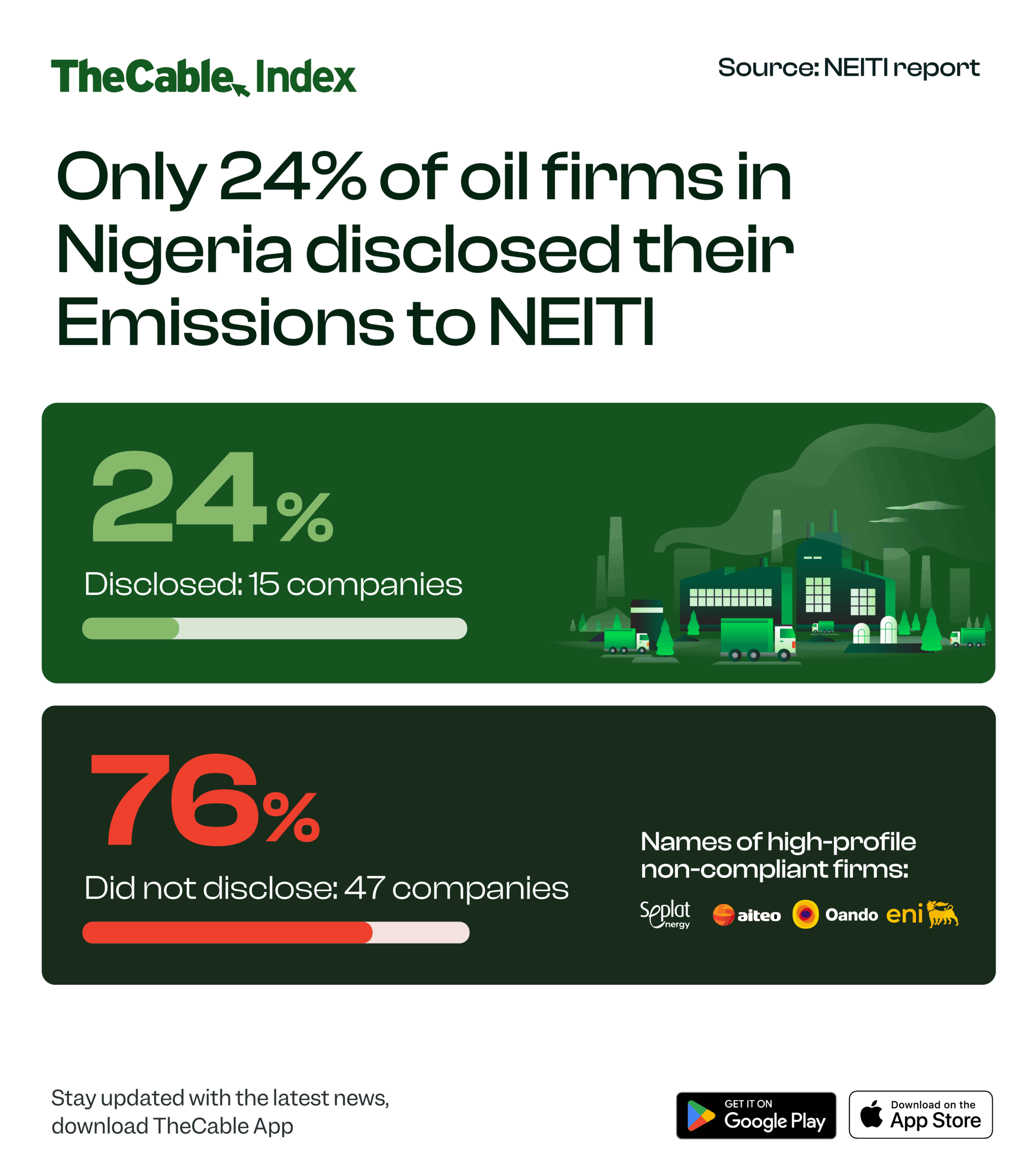

However, the report revealed a troubling trend as only 15 out of 62 oil companies submitted their emissions data, amounting to just 24 percent compliance. Notably, major players like Aiteo, Seplat, Eni, and Oando failed to disclose any data at all.

Advertisement

In 2021, Nigeria enacted the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA), a sweeping reform designed to enhance transparency and regulatory oversight in the sector.

With oil contributing over 50 percent of government revenue and 75 percent of exports, accurate emissions reporting is not just an environmental issue but a matter of economic responsibility and public trust.

NEITI’s emissions disclosure initiative marks a significant turning point. By shining a light on corporate compliance and non-compliance, it lays the foundation for holding polluters accountable and embedding climate responsibility into Nigeria’s oil industry.

Advertisement

Abdulmumin Abubakar, NEITI’s head of oil and gas unit, said emissions disclosure is a new requirement under the 2023 EITI standard, and novel obligation introduced under the PIA 2021 backed by guidelines issued by the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC).

Abubakar said while a few companies are working to build internal systems and policies to comply, many showed limited awareness while others did not provide the data to NEITI as at the time of publication.

“This gap reflects the sectors limited but evolving capacity to meet both domestic and global climate reporting obligations,” Abubakar noted.

He said the 2007 NEITI Act provides for sanctions, including fines and imprisonment, for non-compliance with legitimate data requests, but that enforcement remains weak.

Advertisement

Abubakar said to close this gap, NEITI deploys an existing data request compliance ranking report that indirectly “names and shames” companies that delay, provide incomplete or do not provide information requested for the production of the NEITI Annual audit reports.

“NEITI does not possess direct investigative or prosecutorial powers, the agency relies on other institutions for enforcement — a major barrier to curbing corruption in the extractive sector,” he added.

47 OIL COMPANIES MISSING IN ACTION

NEITI’s report is groundbreaking in that it establishes a baseline for tracking emissions from Nigeria’s most polluting sector. But this milestone is badly undercut by non-disclosure from over three-quarters of the industry.

Advertisement

Notably, some of the most active oil producers including those operating in known gas flaring hotspots like Nembe Creek (AITEO), Oben (SEPLAT), and Nigerian Agip Oil Company’s (NAOC) onshore fields(now owned by Oando) failed to report any emissions data.

Others, like First E&P and Equinor, the report said seem to have taken cover under offshore exemptions.

Advertisement

However, NEITI described this silence as a serious breach of global transparency standards under the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), to which Nigeria is a signatory.

Tengi George-Ikoli, Nigeria country manager at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI), said such reluctance from oil and gas companies to report emissions may stem from fear of regulatory backlash, low technical capacity, or lack of mandatory frameworks.

Advertisement

She noted that time is running out, as the new EU regulations coming into force in 2027 could bar high-emitting products from the market.

“Accurate reporting could expose companies to stricter regulations or legal liabilities, making silence the easier route unless strongly compelled otherwise,” George-Ikoli said.

Advertisement

“It could also affect their ability to access global markets, with EU regulations in 2027 set to restrict the import of high-emitting products, which could affect their bottom line.”

METHANE: THE ELEPHANT IN THE OILFIELD

NEITI’s report paid special attention to methane, a powerful climate pollutant often underreported in the sector.

Methane (CH₄) is a potent greenhouse gas, 84 times more powerful than carbon dioxide (CO₂) over a 20-year period in terms of heat-trapping potential.

Although methane is shorter-lived in the atmosphere (about 12 years), it is a major driver of heatwaves, floods, and dangerous air pollution.

Methane is released from oil and gas operations, agriculture (livestock and rice paddies), waste (landfills and sewage), and coal mining.

In Nigeria, gas flaring continues to pollute the air and waste enormous amounts of energy, with over 16 million tonnes of CO₂ released into the atmosphere, fueling global warming.

According to the National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency (NOSDRA), about 30.1 thousand gigawatt-hours of potential power enough to electrify millions of homes, was lost through flaring in 2024. Yet, many oil companies continue to hide or underreport their methane emissions.

George-Ikoli said the 24 percent disclosure rate is a start, but far from what is needed to drive real accountability.

She urged NUPRC to enforce section 20 of its 2023 gas flaring, venting and methane emission regulations, which mandates that annual methane reports be made public by June 30 of the next year.

George-Ikoli warned that unreliable or missing data could have broader consequences as emissions transparency is the bedrock of credible climate action.

“While NEITI is pushing the envelope, without strong legal mandates for data disclosure and robust monitoring systems, companies face little incentive to comply,” George-Ikoli said.

“Inaccurate or missing data undermines Nigeria’s NDC credibility and impairs access to results-based international climate finance.

“Persistent non-reporting signals, unseriousness to international partners could shut Nigeria out of future climate funding.”

NEITI’s report shows a staggering 99.8 percent drop in methane emissions reported by Chevron from 173 million kg in 2022 to just 270,000 kg in 2023.

The agency flagged this sharp decline as suspicious, warning that without independent third-party verification, such a dramatic reduction raises serious credibility concerns.

Mobil’s methane emissions increased by 15 percent to 256 million kilograms of CO2 equivalent during the same period making it Nigeria’s top emitter in 2023 and undermining its climate commitments. Meanwhile, with 217 million kilograms, Heirs Holdings emerged as Nigeria’s second-highest methane emitter in 2023. There is no data for Heirs in 2022.

George-Ikoli echoed transparency concern, calling for independent verification systems, routine audits, and a standardised MRV (monitoring, reporting, and verification) framework.

WHO IS POLLUTING MORE FOR EVERY BARREL OF OIL PRODUCED?

Beyond just total emissions, NEITI also looked at emissions intensity — how much pollution each company releases for every barrel of oil they produce.

This data is a fair way to compare big and small companies as it shows how efficient or wasteful they are.

The data shows that Heirs Holdings had released over 20 kg of carbon pollution per barrel, while Oriental Energy also performed poorly, with 7.11 kg per barrel. This emission, NRGI suspects, is possibly due to old or inefficient equipment.

Frontier Oil made good progress, cutting its pollution per barrel by 33 percent in just one year.

Pillar Oil’s emissions intensity rose by an astonishing 100,000 percent — from 1.46 kgCO₂-eq per barrel in 2022 to 1,678.58 kgCO₂-eq per barrel in 2023 — a spike NEITI flagged as a likely reporting error or the result of an undisclosed gas-flaring incident.

SATELLITE IMAGERY TELLS A DIFFERENT STORY

While many companies failed to report, an independent satellite analysis from EnergyCC tells a different story.

The data, known as the ‘OPM Report’, identified that 19 of Nigeria’s biggest gas flaring sites, including Chevron’s Agbami, Shell’s Bonga, and ExxonMobil’s Yoho accounted for up to 64 percent of all gas flared in the country.

Yet, in NEITI’s report, most of these “super-emitters” either did not report or omitted field-level details, despite being members of the Oil & Gas Methane Partnership (OGMP), which demands transparency.

This mismatch between what satellites show and what companies report, raises uncomfortable questions. What else is being hidden?

NEITI also observed that most of the companies did not disclose scope 3 emissions.

Scope 3 reporting refers to the disclosure of indirect greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that occur outside a company’s direct operations but are linked to its value chain both upstream and downstream.

For an oil company, scope 3 includes the emissions from burning the fuel it sells even if those emissions happen in cars, planes, or power plants it does not own.

The agency noted that Nigeria must mandate asset-level and scope 3 reporting from all companies.

George-Ikoli said while scope 3 reporting remains ambitious due to fragmented data systems, Nigeria can make progress with phased regulation and technical support.

“Linking emissions disclosure to operational incentives is a proven method. Norway ties environmental performance to license renewals. Canada and Colombia integrate reporting into tax credits and climate funding eligibility. Nigeria can adopt a hybrid model that uses both ‘carrots’ (incentives) and ‘sticks’ (penalties) to drive compliance,” she said.

She added that while Nigeria may not be on a credible path to a just transition, the country needs a national strategy that not only reduces its emissions but also boosts economic diversification, community participation, and workforce reskilling.

This story was produced with support from Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) and Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID).