BY SUNDAY JAMES

The recent call by the corps marshal of the Federal Road Safety Corps (FRSC), Shehu Mohammed, for road safety officers in Nigeria to be armed has reignited debate over the future of traffic law enforcement in the country.

In a recent interview, Mohammed argued that stopping heavy-duty vehicles and enforcing traffic laws on Nigeria’s highways is nearly impossible without firearms. While his concerns about safety and compliance are valid, the idea of arming FRSC operatives is a dangerous detour that could undermine public trust and compromise road safety rather than strengthen it.

Across the world, the most effective road safety systems have been built not on firearms but on technology, strong institutions, and smart collaboration between agencies.

Advertisement

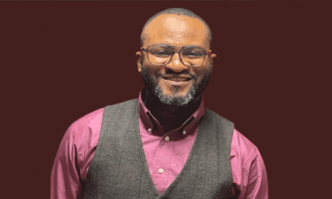

In Sweden, for instance, the adoption of the “Vision Zero” approach, which emphasises safer road designs, strict enforcement through speed cameras, and a focus on human error reduction, has brought road fatalities down to 2.1 deaths per 100,000 people.

The Netherlands, another global leader in road safety, records a similar figure of around 3.4 deaths per 100,000, again without arming its road safety officials. By contrast, Nigeria suffers one of the highest road traffic death rates in the world, with the World Health Organization estimating about 21.4 deaths per 100,000 population annually. This stark difference underscores that the real gap is not firepower but systemic investment in smarter enforcement and safer infrastructure.

The United Kingdom, where the Driver and Vehicle Standards Agency oversees road safety, does not issue firearms to its personnel. Instead, it relies heavily on automated number plate recognition cameras, speed enforcement technologies, and a seamless link between traffic databases and police systems.

Advertisement

In the United States, while state police officers may be armed, civilian road safety and transportation officials operate unarmed, using technology such as traffic sensors, surveillance cameras, and automated ticketing to achieve compliance.

South Africa provides another model closer to home, where traffic officers who are not militarised work hand in hand with the police in cases that require armed response, creating a functional balance that ensures safety without normalising firearms on the roads.

Technology is a far more effective weapon against road lawlessness than guns. Automated number plate recognition systems can instantly flag vehicles involved in violations, while speed and red-light cameras have been shown to reduce traffic crashes by up to 25 percent in cities where they are deployed.

In New York, for example, the installation of speed cameras in school zones reduced speeding by over 60 percent, a clear indicator that digital enforcement changes behaviour more effectively than the threat of violence. Body-worn cameras and dashboard cameras, now standard practice in many jurisdictions, have also reduced incidents of bribery and extortion while providing accountability that builds public trust.

Advertisement

In Nigeria, where allegations of misconduct against traffic officers frequently trend on social media, such technology could help restore the credibility of the FRSC.

Instead of duplicating the role of the police, FRSC should strengthen collaboration with security agencies when situations demand armed intervention. Nigeria already has a police force trained and empowered to handle violent offenders or criminal activities on the highways. What FRSC needs is not to replicate this role but to build joint task forces and rapid response mechanisms that draw on police capacity without compromising its own civilian mandate.

This is not an unusual arrangement; in countries like Australia and Canada, road safety authorities routinely collaborate with law enforcement when issues of crime intersect with traffic management, while retaining their identity as service-oriented, non-militarised institutions.

The risks of arming FRSC operatives far outweigh the perceived benefits. Nigeria’s experience with armed agencies has shown how quickly firearms can be misused against citizens, turning checkpoints into flashpoints for harassment and extortion. The presence of guns on congested roads would increase the likelihood of fatal confrontations and escalate minor incidents into tragedies. Public trust, already fragile, would erode further if citizens come to associate road safety officers with intimidation rather than assistance.

Advertisement

A 2024 public poll reported by PUNCH showed that over 90 percent of Nigerians opposed the idea of an armed road safety squad, with transport unions and civic groups warning that such a move could lead to widespread abuse.

Nigeria urgently needs safer roads, but the answer does not lie in militarising the FRSC. What is required is a deliberate investment in traffic enforcement technologies, rigorous training for operatives in conflict de-escalation and digital enforcement, and a renewed focus on public education that fosters voluntary compliance rather than fear-driven obedience.

Advertisement

The transformation of Nigeria’s driver’s licence system, as promised by the corps marshal himself, is one such opportunity to integrate technology and efficiency into the country’s road safety framework. By streamlining processes and making systems transparent, enforcement becomes less about coercion and more about accountability.

The path to safer roads lies not in the barrel of a gun, but in innovation, professionalism, and trust. If Nigeria truly wants to reduce its staggering road traffic death rate, it must look to global best practices that have proven successful, not to militarisation. Guns will not make highways safer; smarter systems will. The FRSC’s strength should remain in saving lives, not in bearing arms.

Advertisement

Sunday James is a communications and knowledge management professional, public affairs analyst, and doctoral researcher in Development Communication based in Abuja

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.