BY AYOMIDE LADIPO

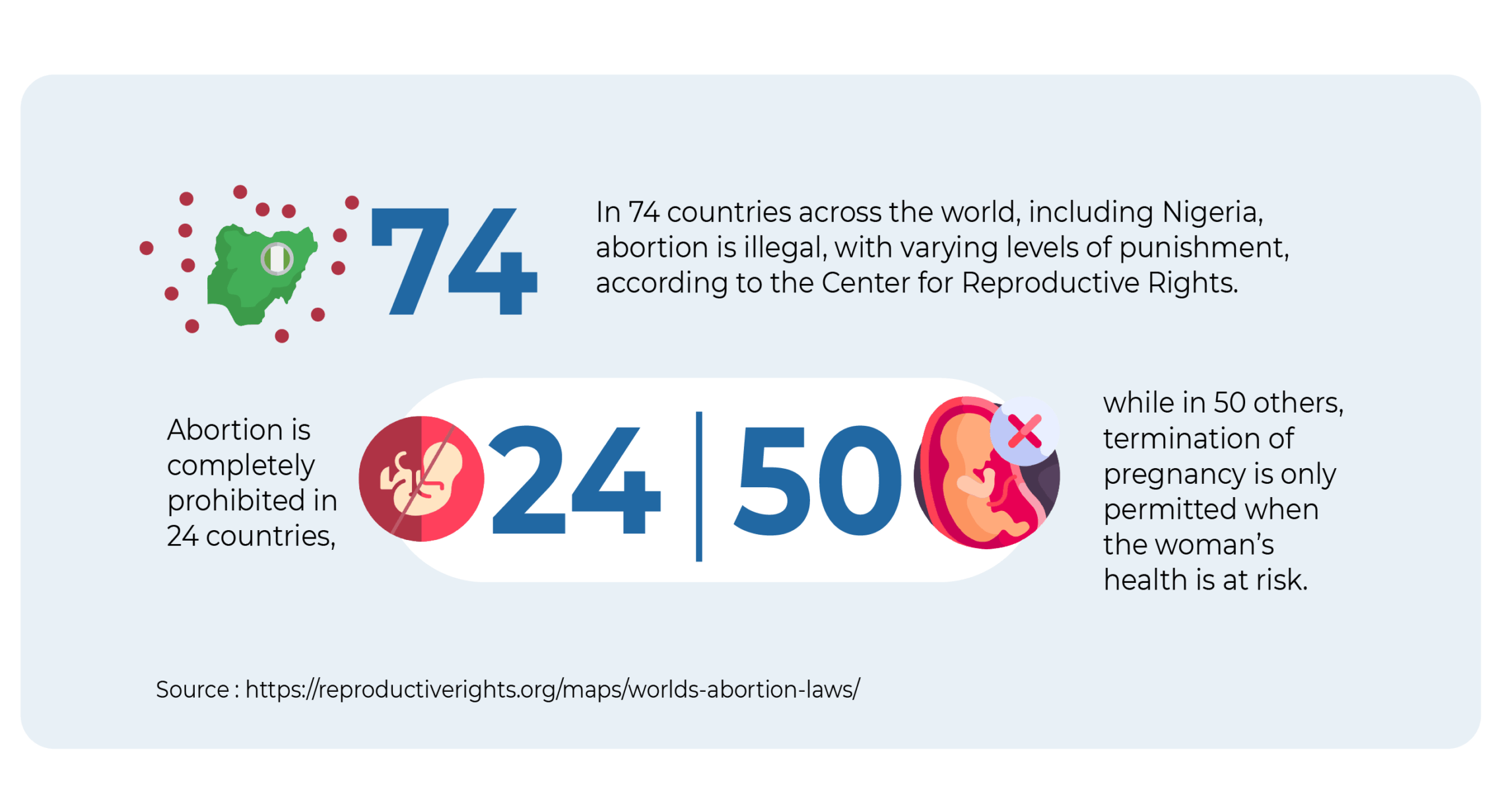

The World Health Organisation recognises abortion as an essential health service to meet the global sustainable development goals. However, in 74 countries across the world, including Nigeria, abortion is illegal, with varying levels of punishment, according to the Center for Reproductive Rights. Abortion is completely prohibited in 24 countries, while in 50 others, termination of pregnancy is only permitted when the woman’s health is at risk.

In Nigeria, abortion is illegal and carries a jail sentence of up to 14 years, unless done to save the life of the pregnant woman, which means post-abortion care is legal. In the Constitution, the Criminal Code Sections 228-230 and Penal Code Sections 232 & 233 criminalise abortion for all parties involved, including the medical personnel, with a jail time of up to 14 years, while Section 297 of the Criminal Code allows for abortion to be done to preserve the mother’s life.

The National Guidelines on Safe Termination of Pregnancy for Legal Indications (STOP), released in 2018 by the Federal Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, provides a comprehensive list of the conditions for which an abortion can be performed to save a woman’s life and deems other conditions as determined by a qualified medical professional. However, the guidelines have not been adopted and domesticated, and all efforts to get the government to adopt them have proven futile so far.

Advertisement

Many Nigerians are unaware that post-abortion care is legal, and such ignorance has contributed to the high mortality rate, as women are unable to access care for complications arising from unsafe abortions. Medical personnel refuse women care at this critical juncture because they want to protect their licences and avoid jail. This situation leaves women who need both abortion services and legal post-abortion care vulnerable to unlicensed and unsafe medical practices while also exposing them to societal stigma and potential ostracism from their communities.

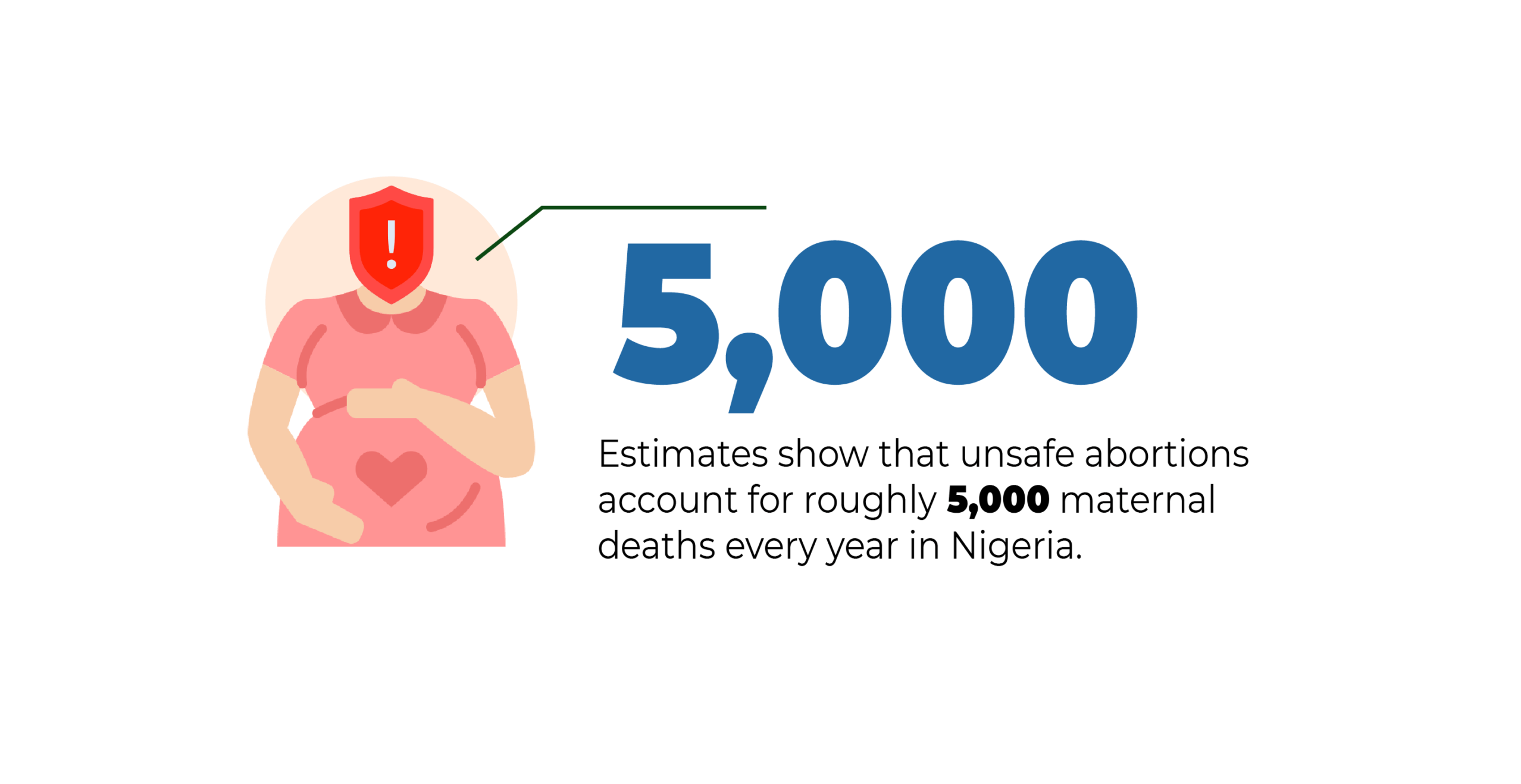

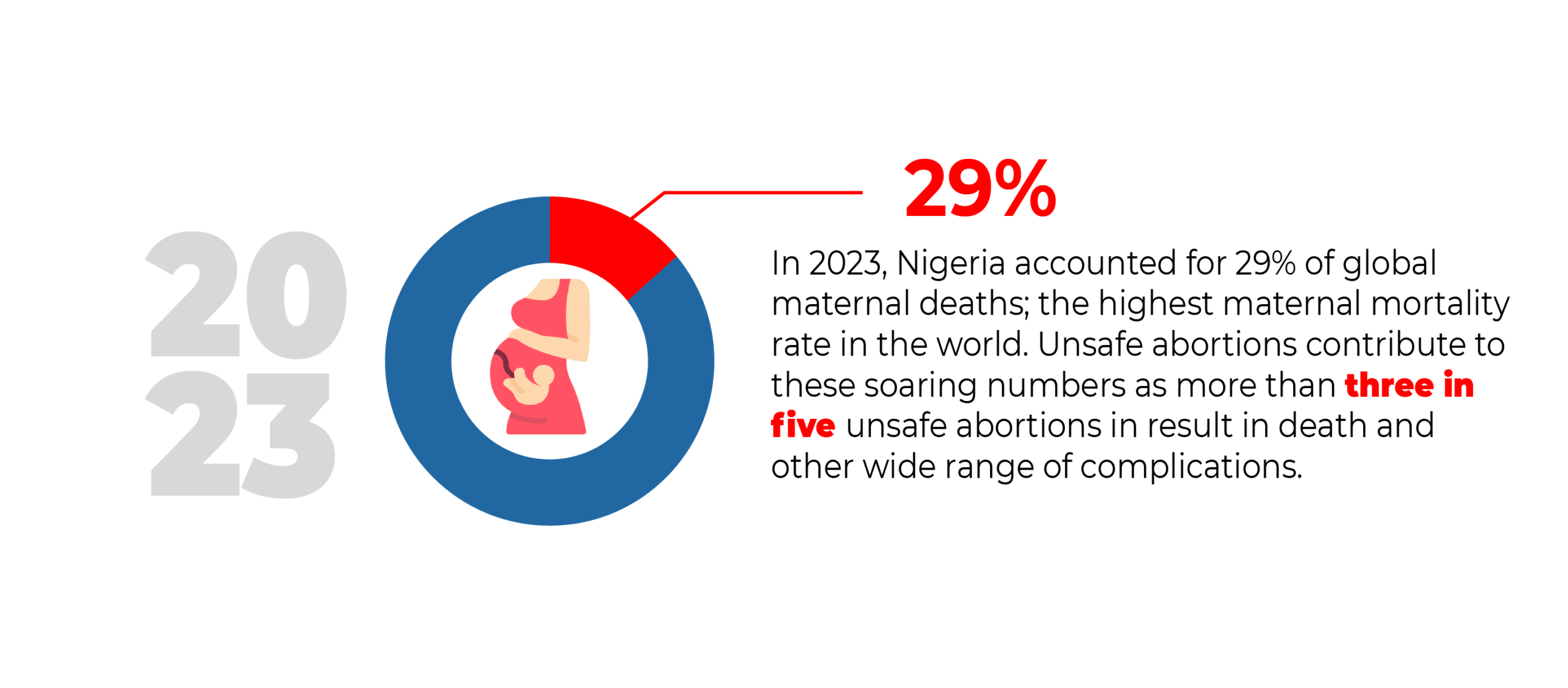

In 2023, Nigeria accounted for 29% of global maternal deaths, the highest maternal mortality rate in the world. Unsafe abortions contribute to these soaring numbers, as more than three in five abortions result in death and a wide range of other complications. Estimates show that unsafe abortions account for roughly 5,000 maternal deaths every year in Nigeria.

BUILDING LIFELINES IN THE SHADOWS OF THE LAW

Advertisement

Due to the crackdown on abortion, Nigerian women have had to rely on a handful of sexual and reproductive health organisations as safe spaces to access this service. Over the years, these organisations have provided abortion and post-abortion services to women in a confidential, non-judgmental, and safe environment with licensed medical professionals. These interventions have been crucial in addressing the issue of maternal deaths resulting from unsafe abortions in Nigeria.

An example of an organisation braving the odds and providing post-abortion care services to women is Komfot Health. Founded in 2024, Komfot Health provides post-abortion care and other sexual and reproductive health services, including HPV screening, STI treatment, and counselling. They also handle physical and psychological complications from unsafe abortion procedures.

Sanasi Amos, the co-founder of Komfot Health, spoke on the importance of the work being done.

“Complications from unsafe abortions go beyond the physical; they can also be deeply traumatic. We once had a young lady who went to a facility for an abortion, but was rejected and referred to a quack. The man she was referred to dipped all his equipment in bleach and inserted it directly into her vagina. The experience was devastating and left her with lasting trauma,” Amos said.

Advertisement

They operate a network of facilities equipped to handle emergencies and post-abortion care, and not all facilities have the capacity for this level of intervention. Komfot finds and trains providers to address their biases and connects clients to them, acting as a “middleman” between women and trusted health facilities. An estimated 40% of women who undergo abortion procedures require post-abortion care, but only 15% actually receive it on time. The rest are untreated or get care too late.

“When people reach out to us, we collect their biodata and details of the problem. If it’s an emergency, we refer them to a trusted primary healthcare facility immediately. We work with primary healthcare facilities because they are everywhere and easily accessible. If it’s an inquiry about a past abortion or ongoing symptoms, we connect them to a chatbot, and then one of our counsellors follows up.” Amos explained.

Komfot refers clients to verified providers for incomplete evacuations. When these are not nearby, they direct clients to pharmacies and connect them to licensed healthcare providers who can issue prescriptions and guide drug use safely.

Technology is central to bridging the post-abortion care gap, and most of Komfot Health’s clients reach out via social media. This necessitated the creation of a chatbot to streamline the process and reduce waiting time.

Advertisement

The chatbot system functions like a digital registration assistant, collecting patient data and location details, referring them to nearby care providers, and alerting medical partners who then design a tailored treatment plan. Counsellors follow up for two weeks after care, providing information, warning signs, and even diet plans for recovery.

Since its inception, Komfot Health has provided post-abortion and reproductive healthcare services to over 1,790 women through approved healthcare providers and facilities in six states: Lagos, Edo, Ekiti, Kano, Rivers, and the FCT. Clients outside these regions rely on an extended provider network.

Advertisement

“One of our success stories was a woman in Ekiti who reached out to say that she was in pain and discomfort four days after the medical procedure. Our provider asked her to go conduct a scan, and the scan revealed she had an ectopic pregnancy, which was in the ninth week,” Amos noted.

“It was a deadly situation, as the drugs she had been asked to take were meant to contract the uterus, and since the pregnancy was not in the uterus, her health was at risk. We referred her to our providers, who provided her with the quality care she needed and saved her life.”

Advertisement

Despite their work, Komfot Health faces backlash. Many accuse them of promoting abortion, which is illegal in the country, but post-abortion care is not, as it is done to save a woman’s life.

“Many women we treat are turned away from hospitals because even medical personnel wrongly believe post-abortion care is illegal. The government must do more to educate health workers and the public to protect women’s lives,” she said.

Advertisement

SAFE SPACES, UNSAFE ABORTIONS

While organisations like Komfot Health are providing critical interventions in a restrictive environment, sister organisations that are also replicating these interventions are blurring the line between care and harm. In many instances, these services are delivered within informal and parallel systems where accountability structures are nonexistent, leading to some women being harmed, exploited, and harassed.

Tola was 24 years old when she visited one of these organisations in 2021. The eight-week pregnancy was hindering her health.

She was directed to pay N150,000 to abort the pregnancy. Despite the exorbitant amount paid, the medical personnel conducted a surgical procedure on her without anaesthesia.

For Tola, the ordeal was excruciating, even beyond the surgical table.

“When I got home, I started cramping badly and the symptoms kept coming,” she recounted.

“I went back, and the doctor did another test and scan and saw that the womb hadn’t been cleared.”

After the second scan, another N150,000 was demanded for another surgery. Tola paid, but the problem persisted.

“The doctor performed the procedure again, and it was the worst pain ever,” she said.

“They kept on saying, ‘Don’t scream, don’t scream,’ but I wasn’t given anaesthesia.”

After a few days with no relief, Tola went back for the third time. The doctor administered a drug. He initially requested N100,000 for the drug, and Tola protested.

Her protest forced a retreat from the doctor, who then claimed he would “help” her and give her the drugs for free. Tola’s trauma mirrors Elizabeth’s story, but in another form.

Elizabeth was in her early thirties and lived in Ibadan at the time she sent a reproductive health clinic a message on WhatsApp. They referred her to a proxy clinic. The experience was harrowing.

“The doctor made me feel horrible. He was interrogating me, asking multiple personal questions and conducting a test, then lied that there was no pregnancy, but I should come back in six weeks,” Elizabeth remembered.

“When I came back, he did a scan and then started trying to convince me not to have the abortion. We spent over three hours going back and forth on why I should not proceed with the procedure.”

When she saw that the reception was hostile, Elizabeth went directly to the organisation’s clinic in Lagos, expecting a different outcome.

After another scan, the doctors demanded N150,000 from Elizabeth for a surgical procedure.

When she protested the fee, the attendant asked, “How much are you willing to pay? We can do N100,000.” She left the clinic when she saw she had to bargain for the service, for her life.

THE DEADLY COST OF MISINFORMATION

For both women, the promise of a safe space collapsed into exploitation and trauma. Their stories highlight a growing danger: when organisations step into the void left by state failures but operate without strong safeguards, they risk replicating the very harm they were created to prevent. While SRHR organisations and bodies continue to pressure the government to relax and reverse its restrictive laws on women’s reproductive health in Nigeria, there is a need to review the activities of organisations that serve as a stopgap.

Elizabeth Adewale, a certified and holistic sex educator, spoke about the need for accountability structures to handle such cases.

“There should be a regulatory body or an organisation that handles accountability and tackles malpractice. Also, organisations should go beyond providing care and prioritise training their staff to unlearn inbuilt biases,” Adewale said.

“Some post-abortion care providers treat their patients with stigma, judgement written on their faces, because they feel like they are aiding a very wrong action. I believe that staff should receive proper training in trauma-informed care, how to support survivors and how to unlearn their religious biases when offering post-abortion care.”

Adewale also highlighted the need for mass education to tackle misinformation and make it easier for women to access these services and speak up when they are abused in their spaces.

“We need to tackle misinformation. There’s a lot of misinformation and myths flying around about abortion. People have the idea that abortions are dangerous; that they’re going to destroy their wombs and their lives,” she said.

“In addition to religious and cultural beliefs, the perception that abortions are dangerous contributes to the restrictions placed on them. But people need to know that it’s unsafe abortion methods that are dangerous. The safe abortion methods are even safer than childbirth. We need to begin to talk about abortion as health care and a human right. That emphasis is very, very important because misinformation is deeply rooted.”

STATE FAILURES, RELIGIOUS RESISTANCE

Some states have attempted reform but consistently buckled under religious and political pressure.

On June 29, 2022, the Lagos state government launched a comprehensive policy document entitled “Lagos State Guidelines on Safe Termination of Pregnancy for Legal Indications”, which sets out guidelines to standardise and build capacity for medical professionals, saving the lives of pregnant women when continuation poses a danger to their lives and physical health.

However, under intense opposition from religious leaders and in a year of federal and local elections, the guidelines were suspended a few days later on July 8. The status quo remains, despite ongoing appeals from women’s rights and civil society organisations.

Lagos was unsuccessful; however, Ogun, its neighbouring state in the south-west, pulled it off.

In May 2023, the Ogun state government implemented its guidelines on safe abortion, which extend legal exceptions to cases of rape, incest, risk to health and specifications around cancer and hypertension, positioning the state as the most progressive in Nigeria on abortion rights.

Elizabeth Enu-Akan, an abortion rights activist, hinted that it was bad timing by the Lagos state government due to the electoral climate at the time.

“Timing is everything. The policy was implemented very close to the election, and we know how our leaders can be about elections. The people have substantial leverage, so the pressure from the traditional and religious groups will get to them,” Enu-Akan said.

“Also, there is a need for discretion and strategic dissemination of information. You can’t just splash the information in the public without proper guidance and context to manage people’s emotions and beliefs. newspaper to splash it. When it comes to sexual reproductive health and rights, it is a sensitive topic for many, especially religious and traditional leaders.”

WAY FORWARD

Despite the restrictions, organisations and SRHR advocates are providing timely interventions to reduce the incidence of unsafe abortions and provide accurate information on reproductive services and commodities in Nigeria. WARDC, a civil rights and feminist organisation in Nigeria dedicated to promoting the rule of law for women and girls, is championing the adoption of STOP guidelines in Jigawa, Oyo, Osun, Gombe, Akwa Ibom, and Anambra states.

Speaking on the adoption of the STOP guidelines by more states, Elizabeth Adewale emphasised data and advocacy.

“At the policy level, we need data-driven advocacy. If we have more people researching abortions in Nigeria, their devastating effects, and the role of the government in curbing them, it will shift the burden of action to the government and highlight the need for them to protect the lives of women who die every day due to unsafe abortions,” Adewale said.

“A 20-year-old girl had an unsafe abortion, and in the process, her uterus got infected, and it had to be removed. Her colon suffered damage during the process, requiring her to live with a colostomy bag every day for the rest of her life. She had to go through all of that because she had an unsafe abortion procedure done by a quack.

“Fifty-four Nigerian women die every day from unsafe abortion procedures. Such incidents must stop.”

This report was produced by Social Voices with support from the Solutions Journalism Network and the Hewlett Foundation, under the Reporting Gender Equity Fellowship, an initiative of Social Voices Media & Development Foundation.