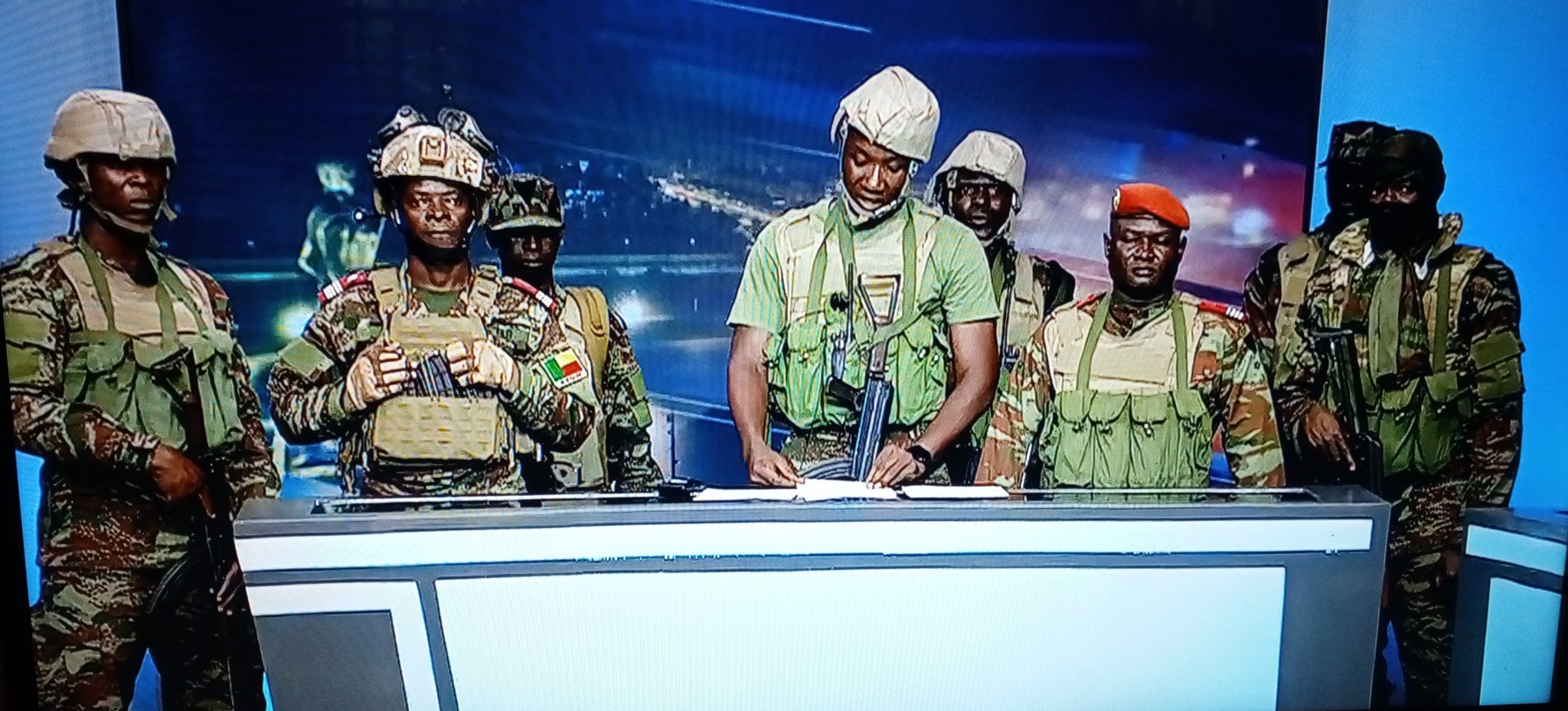

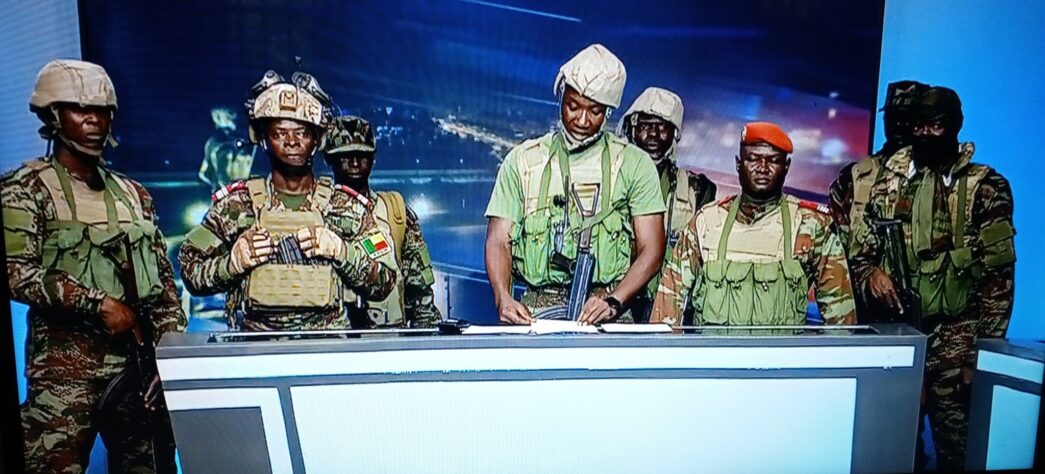

On Sunday, West Africans and Nigerians were left in shock by yet another attempted coup in the Benin Republic, Nigeria’s close neighbour and partner in West Africa, with a very strong cultural link that dates back in history. A group of soldiers led by Lt Col Pascal Tigri had taken over the state media and announced that the elected President Patrice Talon had been removed from power. The rebellious mutineers justified their actions by criticising Talon’s management of the country, complaining first about his handling of the “continuing deterioration of the security situation in northern Benin”. Within hours of the coup, reports emerged that President Bola Tinubu had spoken with French President Emmanuel Macron as ECOWAS leaders moved quickly to prevent another destabilising coup in the region. Soon after, Nigeria deployed fighter jets in coordination with Benin’s authorities to dislodge the coup plotters.

Some people on Nigeria’s social media space, especially on (X formerly Twitter) and some sections of the mainstream media, immediately attacked the move by Nigeria. They called it reckless, unnecessary, or even illegal. But these loud online reactions ignore something very important: West Africa actually has clear rules, agreed to by all member states, that guide how countries should respond when soldiers try to seize power in any member state. And in those rules, Nigeria is not only justified in helping Benin; it is expected to act.

The main legal backing justifying Tinubu’s intervention in Benin or any future intervention comes from two key regional frameworks: the ECOWAS Protocols and the African Union (AU) Constitutive Act. Both documents were created because the continent has suffered too many post-colonial coups and conflicts caused by unconstitutional grabs for power.

ECOWAS’s 1999 Protocol on the Mechanism for Conflict Prevention gives the region the authority to intervene when peace or constitutional order is threatened. It states clearly that ECOWAS may “constitute and deploy a civilian and military force to maintain or restore peace within the sub-region, whenever the need arises.”

Advertisement

The protocol also gives decision-making power to the ECOWAS Mediation and Security Council, which can authorise “all forms of intervention,” including military missions, when democracy is at risk. This is not an idea created overnight. It is a long-standing agreement that every ECOWAS country, including Benin and Nigeria are signatory to.

Then there is the 2001 ECOWAS Protocol on Democracy and Good Governance, which makes the region’s position even clearer. It declares “zero tolerance for power obtained or maintained by unconstitutional means” and states that ECOWAS must act when democracy is abruptly brought to an end. The African Union follows the same principle. The AU Constitutive Act moves away from the old policy of non-interference and says the Union has “the right to intervene” in a member state in “grave circumstances.” While this clause mainly mentions war crimes and mass atrocities, the AU has repeatedly used it, alongside the Lomé Declaration on Unconstitutional Changes of Government, to justify strong regional responses to coups. In short, Africa has learned the hard way that leaving coups unchecked only encourages more coups and more instability. This trend is sadly evident in recent coups in Burkina Faso, Niger and elsewhere in Africa.

This is why the facts surrounding the Benin incident matter. Based on credible reporting from international news agencies, the Beninese government of President Patrice Talon worked directly with Nigeria to repel the coup attempt. President Tinubu later confirmed publicly that Nigerian forces helped to “foil” the attempt, a statement consistent with these reports. When a legitimate government requests help to stop a coup, international law recognises this as a lawful “intervention by invitation.” So Nigeria was not violating the territorial integrity of Benin or acting as a bully or playing big brother. It stepped in because its neighbour asked for help – and because ECOWAS rules demand a strong response when democracy is attacked.

Advertisement

Unfortunately, social media often turns serious issues into noise and fearmongering. On X, people rushed to frame Nigeria’s action as aggression or warmongering. Many of these arguments ignore the region’s legal frameworks, past precedents, and the real danger of allowing soldiers to forcefully remove a democratically elected government. When a small group of soldiers overturns an election, it does not stay a “local problem.” It affects borders, trade, security, and stability across the region.

West Africans just witnessed how coups in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger fuelled insurgency, displacement and economic hardship. ECOWAS simply cannot afford another coup, especially in a country like Benin, which sits in a sensitive corridor between coastal West Africa and the Sahel. In the wake of the Benin coup, many Nigerians have also questioned why President Tinubu acted quickly but was not decisive when the military toppled President Bazoum in Niger last year. The answer is simple but important. The Niger crisis was far more complicated. At the time, ECOWAS did threaten force, but unlike Benin, the ousted Nigerien government could not request intervention because the president was detained and isolated by the junta. Several powerful states in the region, including Mali, Burkina Faso and Guinea, which were already under military rule openly backed the junta in Niamey. This created a bloc of resistance that made any ECOWAS military action risk dragging the entire Sahel into a wider regional conflict.

Most importantly, France, the United States and the UN sent mixed signals, each calculating its own strategic interests. And inside Nigeria, public opinion was heavily divided, with many citizens opposing war. Tinubu was the chair of ECOWAS, but he was not free to act alone. ECOWAS operates by consensus, and that consensus collapsed under the weight of regional politics and fear of escalation. Benin, by contrast, presented the textbook scenario ECOWAS protocols were written for: a small group of soldiers attempting to overturn an elected government, and that government still intact, still functioning, and still able to request assistance. There was no geopolitical complication, no rival military bloc defending the coupists, and no divided mandate among ECOWAS leaders. For once, the region had clarity, and Tinubu acted within that clarity.

Nigeria’s role in Benin thus carries both legal backing and regional responsibility. As the largest democracy in West Africa, Nigeria has a duty to help stabilise the neighbourhood when invited and when the law allows. What would have been irresponsible is doing nothing while a coup plot succeeds next door.

Advertisement

Still, democracy must be allowed to serve its purpose. Across Africa, democracy has not been allowed to thrive, and good governance is still far from being realised, as many elected representatives have continued to disappoint. Corruption is still rife across the and many Africans are living in poverty. Many people are disillusioned and seeking messiahs as their leaders have failed them. These conditions provide the fertile ground for a military takeover to take hold. But the worst of democracy is still better than the best of military government. But African leaders must provide good governance and lift their people from poverty. Only then can stability be guaranteed. Africa cannot afford to return to its past, but democratically elected leaders must provide the needed leadership and avoid conditions that make military intervention the hope of the people.

But overall, the principle remains simple. ECOWAS and the AU built these frameworks to prevent the continent from sliding back into chaos. Nigeria’s intervention in Benin was not reckless. It was the fulfilment of a regional promise: that power must come from the ballot, not the barrel of a gun.

Follow Bayo Olupohunda on X @BayoOlupohunda

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.