BY EZENWA NWAGWU

Recently, there have been several conversations around the registration of new political parties by the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) and the submission of letters of intent by associations seeking to be formally recognised.

This moment, I believe, offers an important window to have a wider conversation about some of the changes that have quietly taken place in our electoral process, and bring to the attention of citizens how these processes really work.

Why is this window so necessary? First, to make sure politicians, true to their usual character of mastery in obfuscation, lies, and demagoguery, do not hijack the narrative and exploit the assumed naivety of many Nigerian voters.

Advertisement

As someone deeply invested in understanding the electoral process, I have always been concerned with the behaviour or misbehaviour of politicians and their ability to manipulate public imagination and release talking points to the media through deliberate subterfuge

For instance, some politicians have recently started to claim that INEC is denying them the opportunity to register their new political parties. But the facts tell a different story: there are currently 122 associations that have submitted letters of intent to INEC seeking registration.

It’s important to clarify that this is only the first step in the process. At this stage, these groups remain associations, not yet officially recognised political parties. The registration process itself involves multiple stages, which I’ll discuss later in this article.

Advertisement

My aim in this piece, therefore, is simple: to highlight some of the major yet often overlooked reforms that have happened in recent years, beyond just the introduction of technology. While flashy gadgets often grab the headlines, there is a lot more to the story of how our elections are slowly but meaningfully improving.

The first is to say that when Dr. Alex Otti was declared the winner of the Abia state governorship election in March 2023. It wasn’t just another election victory it felt, too many. It was a testament to a small but powerful symbol of how Nigeria’s electoral system has been learning, adapting, and slowly but surely improving.

For those who don’t remember what happened. After reports of massive irregularities in Obingwa local government area, INEC, exercising a relatively new power granted under the Electoral Act 2022, stepped in to review the contested results.

For me, that moment captured the slow, sometimes painful, but very real evolution of Nigeria’s elections. It invites us to ask: What other reforms and innovations, especially between 2015 and 2025, have quietly shaped our democracy, even if they haven’t fixed everything overnight?

Advertisement

Looking back, this power of review marked a quiet but historic shift in Nigeria’s electoral process. Before the 2023 elections, once a returning officer made a declaration, even if it was clearly made under duress or based on fake figures, INEC’s hands were effectively tied.

Aggrieved candidates had to spend months, sometimes years, battling in court, while the controversial winner enjoyed the advantages of incumbency. The Electoral Act 2022 changed that script, giving INEC the legal backbone to step in quickly and correct obvious abuses of the process.

But that’s just one piece of the puzzle. Over the past decade, Nigeria’s elections have been shaped by a mix of legal reforms, institutional changes, and technological innovations.

The biggest challenge is our tendency to overlook incremental progress. Too often, Nigerians dismiss partial reforms or evolving changes simply because they don’t deliver instant, revolutionary results. But democracy is not built overnight. It unfolds in stages — sometimes painfully slow but meaningful, nonetheless.

Advertisement

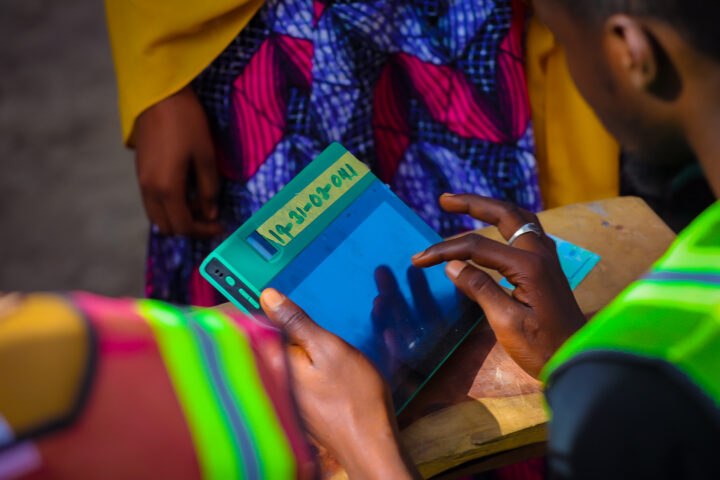

It is true that Nigerians are more familiar with the introduction of real-time transmission of results with the IReV portal, the introduction of the bimodal voter accreditation system (BVAS) that has helped reduce multiple voting, and the growing use of technology to limit human interference, there, however, have been the less visible but equally important improvements such as investing in purpose-built collation centres, better training for ad hoc staff, and clearer guidelines for political parties and security agencies. All of these steps, taken together, helped to chip away at the deep mistrust that had long haunted Nigeria’s elections

For instance, many Nigerians may not remember that as of 2015, only a few INEC state offices had large halls for the collection of election results. Collation was done in hotels or event centres.

Advertisement

Today, all INEC state offices have a large hall within their premises for collation and declaration of results. Little changes like this may not get the attention of the media, but they help strengthen processes. Recall when thugs invaded collation centres and disrupted the declaration of results? Or when returning officers were held at gunpoint at government houses and forced to declare results?

Also, beyond technology at polling units, one of the quiet but transformative reforms of the last decade happened behind the scenes — in how political parties conduct their primaries and how their candidates are officially recognised.

Advertisement

Before the reforms, the process of submitting candidates’ names to INEC was largely manual, paper-based, and, frankly, chaotic. Party leaders could “swap” names at the last minute, sometimes after candidates had genuinely won primaries. This led to endless court cases, bitter intra-party disputes, and a sense among party members that the real contest wasn’t at the primary but at the party headquarters, where lists could be doctored before submission.

Starting around the 2019 cycle and strengthened further by provisions in the Electoral Act 2022, INEC introduced online portals for political parties to submit the names and details of candidates who emerged from primaries. Parties now must upload results and supporting documents directly to the INEC candidate’s nomination portal (ICNP), with strict deadlines.

Advertisement

This shift achieved several important things: Reduced last-minute substitution. It became harder for parties to change names outside the clear legal window because submissions were timestamped and stored electronically. It also improved transparency, ensuring that party members, journalists, and election monitors could follow the process more closely and spot when parties tried to bend the rules. It has also streamlined litigation. Courts could rely on digital records directly from INEC rather than conflicting “official” letters from party factions.

Even more significantly, the law now requires parties to submit a list of their members to INEC ahead of primaries, meaning that only verified members can vote in these internal contests. While enforcement still faces challenges — especially in parties where internal democracy remains weak — the framework itself is an improvement on the pre-2015 days, when almost anyone could be shipped in to vote at a “primary” held overnight in a hotel hall.

All of this might sound technical, but it has huge consequences: by tightening control over candidate nomination and making the process electronic, the system helps ensure that the names on the final ballot better reflect the choices made at the grassroots, rather than the will of a handful of powerful party figures.

It also matters because Nigerians often speak passionately about strengthening democratic institutions. But the conversation is usually limited to INEC, the judiciary, and sometimes the media. We forget or perhaps have been made to believe, that political parties themselves are not part of democratic institutions.

Sadly, at every turn of improvement, politicians continue to find new ways to subvert the will of the people. In 2023, for instance, we witnessed large-scale vote buying. But the truth is, vote buying itself is really the politicians’ reaction to reforms introduced by INEC that have made ballot box snatching almost useless.

Have you wondered why politicians now pay as much as N20,000 to buy a single vote? Do you truly believe Nigerian politicians have suddenly become generous? The reality is that they now understand that INEC has shifted power back to the people, and it terrifies them.

This takes me back to the ongoing conversation around the registration of political parties and some of the narratives politicians are pushing.

Former Governor Rotimi Amaechi, a man who put in close to three decades as speaker, governor, minister and ought to know better, during a recent TV appearance, openly accused INEC of refusing to register the All Democratic Alliance (ADA), one of the new political parties he is promoting.

In my view, politicians like Chibuike Amaechi see elections as a game: a contest of who can outsmart or outmanoeuvre the other side. But for INEC and for ordinary Nigerians, elections should be a serious business. It becomes dangerous when politicians try to bend or manipulate democratic institutions to suit personal ambitions.

Those of us who work hard to understand the electoral process have a responsibility to speak up rather than remain silent while politicians chip away at the credibility of these institutions.

The truth is, there are clear guidelines for registering a political party: interested associations submit a letter of intent to INEC. It’s not so different from registering a business with CAC. INEC has a 90-day window to verify the proposed party name, after which applicants provide details like names of national officers, office address, and other required documentation, which INEC is also required by law to verify.

After this, the main application process begins, with the applicants now required to pay the application fee and filling of the application form, known as Form EC15A(1)

Interestingly, during that same interview, Amaechi admitted that ADA was yet to complete the process, saying they planned to submit the required documents “next week.” Yet, in the same breath, he accused INEC of blocking the registration of the party. How do you explain this deliberate contradiction?

As someone concerned with our democratic process, I worry that Amaechi’s critique of INEC may be part of a broader resistance to reforms that reduce the stranglehold of political elites over election outcomes. The gradual democratisation of Nigeria’s elections has shifted power from political kingmakers back to the ordinary voter. This shift unsettles those used to manipulating the system to decide who wins and loses.

Nigerians must start asking hard questions of the political class: What have they tangibly done to strengthen electoral reforms or deepen democratic culture? Many of these figures have been the greatest beneficiaries of democracy, yet often contribute the least to their advancement. Instead of working to improve the system, their energy is mostly directed at winning power, by any means necessary.

Despite all this, the quiet truth remains: Nigeria’s elections have improved. From party primaries to candidate nomination, logistics, training, and technology. The journey isn’t finished. But the progress, though imperfect and sometimes invisible, is real.

Ezenwa Nwagwu is the executive director of Peering Advocacy and Advancement Centre in Africa (PAACA).

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.