What began as a hopeful return of citizens and regional migrants at the restoration of democracy has turned into an another prolonged story of departure. Over the past 26 years, Nigeria has shifted from being a destination for migrants to a country many are choosing to leave.

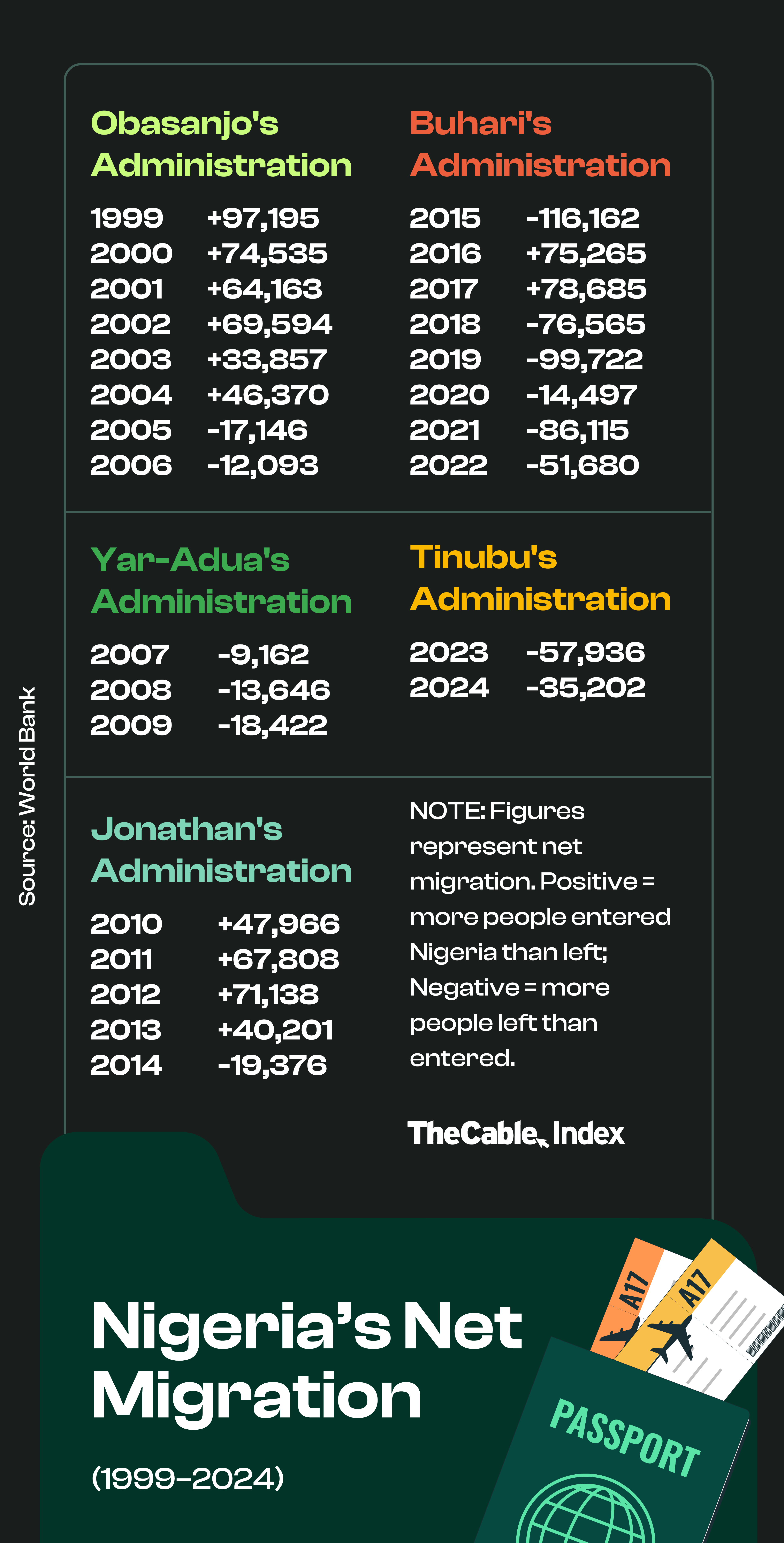

An analysis of World Bank data by TheCableIndex, the data and research arm of TheCable, shows that between 1999 and 2024, Nigeria recorded alternating years of gains and losses in net migration, with 15 of those 26 years posting negative balances. The early 2000s were marked by consistent inflows, but the trend has since reversed, especially from the mid-2010s.

The most dramatic drop came in 2015 when the country lost over 116,000 people to migration — the worst year on record. Since 2018, Nigeria has recorded seven consecutive years of net emigration, reflecting deepening economic hardship, rising insecurity, and growing disillusionment, particularly among young professionals.

Net migration refers to the difference between the number of people entering a country (immigrants) and those leaving (emigrants) in a given year. If more people arrive than leave, the figure is positive.

Advertisement

If more leave than arrive, it is negative. It is a key indicator of how attractive — or unstable — a country is perceived to be, especially when tracked over time.

Although Nigeria’s total net migration between 1999 and 2024 remains slightly positive, that national balance conceals wide differences across administrations.

Advertisement

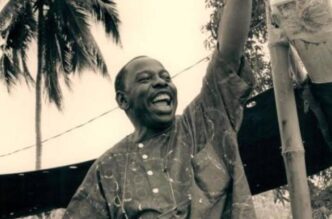

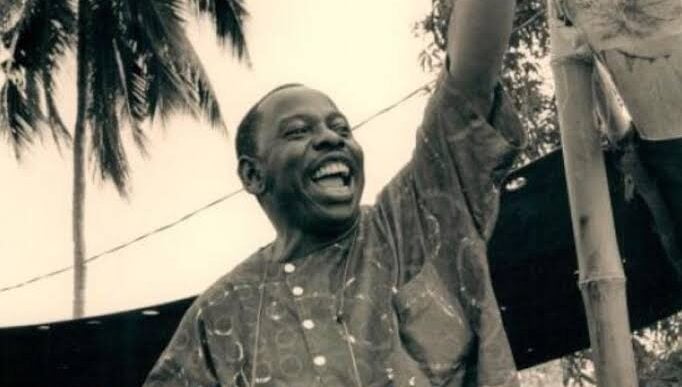

Under President Olusegun Obasanjo, the country recorded a net gain of over 356,000 people, reflecting renewed confidence in post-military Nigeria and strong regional migration inflows. The short tenure of Umaru Musa Yar’Adua saw a net loss of about 41,000, amid early signs of declining confidence.

President Goodluck Jonathan reversed the outflow, with Nigeria gaining over 207,000 people during his five-year term, bolstered by an oil-driven economy and relative political stability.

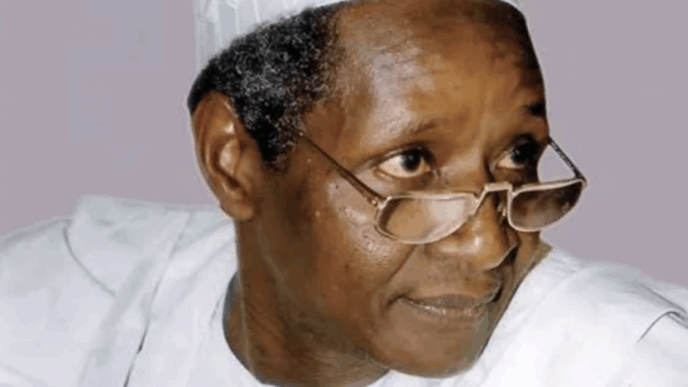

However, the trend turned sharply under President Muhammadu Buhari. Between 2015 and 2022, Nigeria recorded a net migration loss of more than 290,000, the worst under any administration in the fourth republic.

The outflow has continued under President Bola Tinubu. In just two years (2023 – 2024), the country has already recorded a further net loss of over 93,000 people, signalling the persistence of the crisis.

Advertisement

NIGERIA SPENDS TO TRAIN, BUT OTHERS GAIN THE SKILLS

The reasons behind Nigeria’s growing migration crisis are neither abstract nor new. Over the past decade, a combination of economic strain, worsening insecurity, and deteriorating public infrastructure has pushed many Nigerians, especially skilled professionals, to seek better opportunities abroad.

For young people, the lack of jobs, rising inflation, and erratic power supply are daily reminders of a system that no longer inspires confidence. For professionals like doctors, engineers, and academics, the problem cuts deeper — inadequate pay, poor working conditions, and a lack of institutional support have made it difficult to justify staying.

The health sector offers one of the clearest illustrations of Nigeria’s migration crisis. TheCableIndex analysis of data from the Nigerian Association of Resident Doctors (NARD) and the Federal Ministry of Health revealed that more than 30,000 doctors left Nigeria between 2005 and 2024.

Advertisement

Between 2007 and 2014, during the Yar’Adua and Jonathan administrations, about 8,956 doctors left the country. That figure nearly doubled under President Muhammadu Buhari, with an estimated 13,256 doctors exiting during his tenure. In the current administration of President Bola Tinubu, 5,391 doctors have already left in just two years.

The outflow has accelerated sharply, with 3,974 doctors leaving in 2024 alone — the highest annual figure recorded in two decades.

Advertisement

On April 8, Ali Pate, coordinating minister of health and social welfare, said it costs over $21,000 to train a single medical doctor in Nigeria.

Pate said the growing exodus of doctors represents a major fiscal loss for the country, given the high cost of training and the increasing number of medical professionals leaving.

Advertisement

He noted that the trend has worsened Nigeria’s doctor-to-population ratio, which currently stands at 3.9 per 10,000 people — far below the global minimum.

Pate attributed the migration of doctors to better economic opportunities, improved working conditions, and more advanced research environments available abroad.

Advertisement

OFURE: I WANT MORE THAN NIGERIA CAN GIVE

For Ofure, a young pharmacist in her late twenties, the decision to leave the country was not made on a whim — it was shaped by lived experience.

“I started thinking seriously about leaving Nigeria during my NYSC,” she said.

“My NYSC started in a community pharmacy. Then it was changed to a government hospital, which means I had firsthand experience from two different practice settings, and the problem was the same.

“Besides the poor payment and being overworked, practising in Nigeria isn’t something I want for myself in the long run.”

Like many of her colleagues, Ofure is not just chasing better pay, she’s searching for professional dignity and growth.

“My motivation is good pay, working conditions, or something deeper. Also, practice in this part of the world is very limited. I want options. I want good pay, I want good work conditions,” she said.

“From being overworked to not being paid well, there’s also the part where I want to experience more — and Nigeria currently doesn’t have that to give.”

Still, her passion for medicine remains.

According to her, what sustains her is the impact she makes. But the reality is that she is ready to leave anytime soon.

“I really do enjoy it even though sometimes I get overworked. I love the interactions, the education and seeing people get better,” she said.

But she is clear-eyed about the limits of passion in a system that undervalues care workers.

Chidozie Pascal, a clinical and public health practitioner and founder of Pandacare, a health-tech company, also told TheCable that a combination of deep frustration and survival drives the exodus of healthcare professionals from Nigeria.

According to him, many medical workers are leaving not just in search of better pay but also for environments where their work is valued, their skills fully utilised, and their well-being prioritised.

“Imagine dedicating over seven years to intense medical training only to end up working in poorly equipped hospitals, earning meagre salaries, and facing daily burnout due to workforce shortages,” he said.

“It’s disheartening. Sadly, it’s gotten so bad that even respected elders and mentors in the medical profession who once encouraged resilience are now openly advising and encouraging young doctors to leave the country. That speaks volumes about the level of despair in the system.”

He added that doctors’ departure has significantly affected patient care, noting that many communities are now left with skeletal services.

HUMAN CAPITAL LOSS, REMITTANCE GAINS

According to World Bank data, between 2010 and 2024, Nigerians abroad sent home over $318 billion in remittances. Annual inflows averaged between $19 billion and $21 billion for much of the period, with occasional spikes, including a peak of $30 billion in 2017.

In 2024 alone, remittances hit $20.98 billion, underscoring Nigeria’s continued reliance on its diaspora to stabilise household incomes and supplement foreign exchange earnings.

While these inflows offer short-term relief to families and contribute to the country’s balance of payments, they mask a deeper structural cost — the steady depletion of Nigeria’s skilled workforce.

Nowhere is this more visible than in the health sector. Each doctor who leaves Nigeria represents years of public investment, often subsidised through heavily funded medical schools and government hospitals.

Yet, instead of serving the system that trained them, these doctors now work in foreign health systems — in the UK, Canada, Saudi Arabia, and beyond — where their services are welcomed without the burden of training costs.

What remains is a deepening crisis at home. As of 2022, the national doctor-to-patient ratio stood at 1:3,749, based on data from the Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria (MDCN). But that average hides regional inequalities. In Jigawa, there is just one doctor to over 27,000 people.

In Zamfara, the ratio is 1:20,533. Several northern states have ratios well above 17,000 patients per doctor — an alarming indicator of how migration is hollowing out frontline service delivery.

Even in better-served areas like Lagos (1:1,762) and the FCT (1:633), the pressure on doctors is immense, driven by high demand, internal migration, and limited retention.

Remittances may boost dollar inflows but not replace the institutional void left behind.

This trade-off may appear economically beneficial in the short term, but the long-term consequences — for health, education, and national development — are far more costly.

Chimere Iheonu, an economist and postdoctoral fellow at the University of South Africa, agreed that migration can boost remittance inflows and contribute to economic activity.

However, he pointed out that remittances are not a sufficient substitute for sustained economic growth and national development.

“Remittances are not enough to compensate for economic growth and development, particularly in the long run. There has been a significant loss of critical skills in medical fields and academia,” he said.

“Remittances would not be able to compensate for the loss of our doctors, nor would they compensate for the loss of academics who have all left the shores of Nigeria.

“Both the health and education sectors are the most crucial for economic growth and development, which remittances might not be able to scale.”

Iheonu said the education sector has also been hard hit, noting the disparity in earnings between countries.

“Human capital has the highest return on investment compared to any other form of investment globally,” he said.

“A lot of Nigerians are frustrated about the political environment of Nigeria and the lack of hope in the future.

“A professor earns less than N500,000 in Nigeria but earns almost N7,000,000 in South Africa.”

As migration figures continue to rise, experts warn that unless Nigeria takes deliberate steps to retain its talent, the country will keep funding the development of other nations, while its own systems weaken.