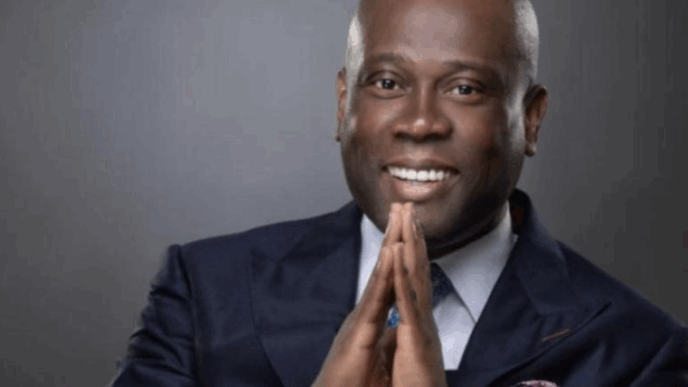

BY JUNAIDU MAINA

“One of the great challenges in life is knowing enough about a subject to think you’re right, but not enough about the subject to know you’re wrong” – Neil Tyson

After decades in livestock development, I’ve learned this: some of the biggest policy failures often stem not from ignorance, but from the “known unknowns” we choose to ignore. Hiding in plain sight are the cultural norms, gender dynamics, power plays, and economic realities that decide who really owns the animals, who calls the shots, and who trusts the system. Ignore them, and even the best programmes crumble.

In this piece, I share four real-life examples from Nigeria that show why understanding these dynamics is crucial for designing and implementing effective livestock policies.

Advertisement

Rinderpest: A Memory Fading Too Fast

The first, during Nigeria’s last major Rinderpest outbreak in the 1980s, it was not uncommon for a pastoralist to wake up and find his entire herd lying dead, wiped out overnight by this devastating disease. Travellers often saw cattle carcasses lining highways, stark reminders of a national livestock emergency. Some livestock keepers were so overwhelmed that it tragically led to suicides.

In contrast, cattle that had received the highly efficacious Tissue Culture Rinderpest Vaccine (TCRV) remained healthy and were visibly thriving. A single dose provided lifelong immunity, leading to the global eradication of rinderpest in 2011—much like smallpox in humans. This remarkable success became a powerful endorsement of vaccination and helped build lasting trust in veterinary services.

Advertisement

The impact extended beyond animal health. Many pastoralist communities, having experienced the benefits of livestock vaccination first-hand, became strong advocates for human health initiatives such as the National Programme on Immunisation (NPI) and the Polio Eradication Campaign—government initiatives aimed at protecting children from vaccine-preventable diseases.

Sadly, this legacy is under threat. In several countries, growing anti-vaccination sentiments—driven by social media and local politics—are undermining this vital animal health approach and strategy. In many African countries, vaccination rates remain very low, while livestock diseases already account for over 20% of production losses each year, reducing food supply and increasing greenhouse gas emissions per unit of meat and milk produced.

Swift action is vital to restore public trust in vaccination, reduce antimicrobial use, and prevent economic losses.

From Misunderstanding to Misguided Policy

Advertisement

The second, the governor of a Nigerian state, named after a famous river whose valley has, for centuries, been ECOWAS’s most historic pastoral dry-season grazing retreat, was sold the fallacy that ‘ranching’ is the only global best practice for cattle keeping. A notion that’s pure nonsense in the African context. So in 2017, this state — Netherlands-sized (land only), located at the crossroads of two international usufructuary transhumance routes and hosting three of Nigeria’s eight officially gazetted Inter-state Veterinary Control Posts— enacted The Open Grazing Prohibition and Ranches Establishment Law.

Enforced with zeal, the law criminalising pastoralism has plunged the state into a protracted crisis and a rising toll of lives.

A stark reminder that a misunderstood concept can spawn policies that cause more harm than good.

Beyond the Household Head: The Others Who Count.

Advertisement

A third issue concerns the pattern of cattle ownership within small-scale producer households—especially polygamous ones. In many such families, each wife owns and surreptitiously manages her own cattle, yet in external engagements with veterinary officials, researchers, or development agencies, the husband typically presents himself as the sole owner of the herd.

This creates a false picture of ownership, often leading to misaligned interventions. For example, productivity-enhancing initiatives such as improved feeding or veterinary care may stall when it’s unclear who is responsible for covering the costs of the feed or vaccines. When ownership is hidden or dispersed, it becomes difficult to identify the true beneficiaries — and with that, responsibility and accountability are easily lost.

Advertisement

Without a clear understanding of intra-household dynamics—especially around power and control—interventions risk being ineffective or inadvertently deepening existing inequalities.

Insights from Nigeria’s Avian Influenza Compensation Programme.

Advertisement

The fourth case emerged during Nigeria’s 2006 fight against Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI). A key pillar of the response was compensating affected commercial poultry farmers—not just as financial relief, but as a trust-building tool to support the government’s modified stamping-out strategy

Rates were carefully calibrated: high enough to encourage reporting and restocking, but not so high as to incentivise complacency. Public ceremonies were held, and beneficiaries’ names were published in National dailies to ensure transparency.

Advertisement

However, the process revealed interesting dynamics that had previously gone unnoticed. As chief veterinary officer at the time, I began receiving phone calls. Men expressed concern about being exposed to robbery and scams due to the publicity. But women were asking a very different question: “Did my husband actually receive the compensation—and if so, how much?”

That was the moment it all became clear — many of the poultry farms were actually owned by women. Yet due to the legal and cultural restrictions at the time, most couldn’t open bank accounts in their own names. Payments were therefore made to their husbands— some of whom claimed they received nothing — leaving the real flock owners both uncompensated and invisible.

This revealed a deeper systemic issue: gendered barriers to financial inclusion, and the limited recognition of women’s roles in livestock value chains. It also highlighted how misunderstood household dynamics can undermine even the most carefully designed intervention.

Forward Thinking: Lessons for the Future

Productivity gains mean little if the benefits stay lopsided. Ignore household power dynamics, and even the best intentions can deepen inequality

Change is happening—but it’s just the beginning. Nigeria’s shift to a cashless economy and expanding digital financial services are closing vital gaps, empowering more women to take charge of livestock production.

Policymakers must seize this moment: scale up telemedicine, champion digital innovations, and prioritise inclusive access.

Policy’s role is clear: engage all stakeholders, centre the people who matter most and build local capacity. In sub-Saharan Africa, livestock productivity isn’t just about animals — it’s about equity, resilience, and food security for millions.

Dr Junaidu Maina can be contacted via [email protected]

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.