Open communication on family planning with a group of women. Image Credit: Anibe Idajili

BY ANIBE IDAJILI

“No, not another one,” Hauwa* exclaimed one evening in July 2024, fearing she was pregnant again following persistent nausea and a delay in her menstrual cycle. She sank under the weight of exhaustion amid the cries of hungry children in her home.

Her husband, Mallam Musa, a farmer in Ungwan Galadimma, a rural community in Niger state, believed in the “divine blessings” of many children, guided by his Islamic faith. So, at 28, Hauwa was already a mother of four, her body enduring pregnancies and the demands of an expanding household.

While Hauwa also loves children deeply, another pregnancy, just eight months after the birth of her last child, would surely break her. She had heard of modern methods of preventing pregnancy from a cousin, but the thought of discussing it with Musa, or even approaching a primary health centre, filled her with dread. It felt like betraying her faith, her culture, and the man she revered.

Advertisement

Just one kilometre away lay the Kontagora Central Ward Primary Health Centre. Inside, Kabiru Umar, the assistant nurse-in-charge, greeted his next patient with a gentle smile and an understanding of the intersection of tradition, faith, and the struggles that define women’s lives in conservative northern Nigeria.

He hadn’t always approached his work this way. Before, it was about simply offering services. But a new training on providing inclusive and empathetic family planning services had changed his perspective, opening his eyes to the power of truly listening and understanding.

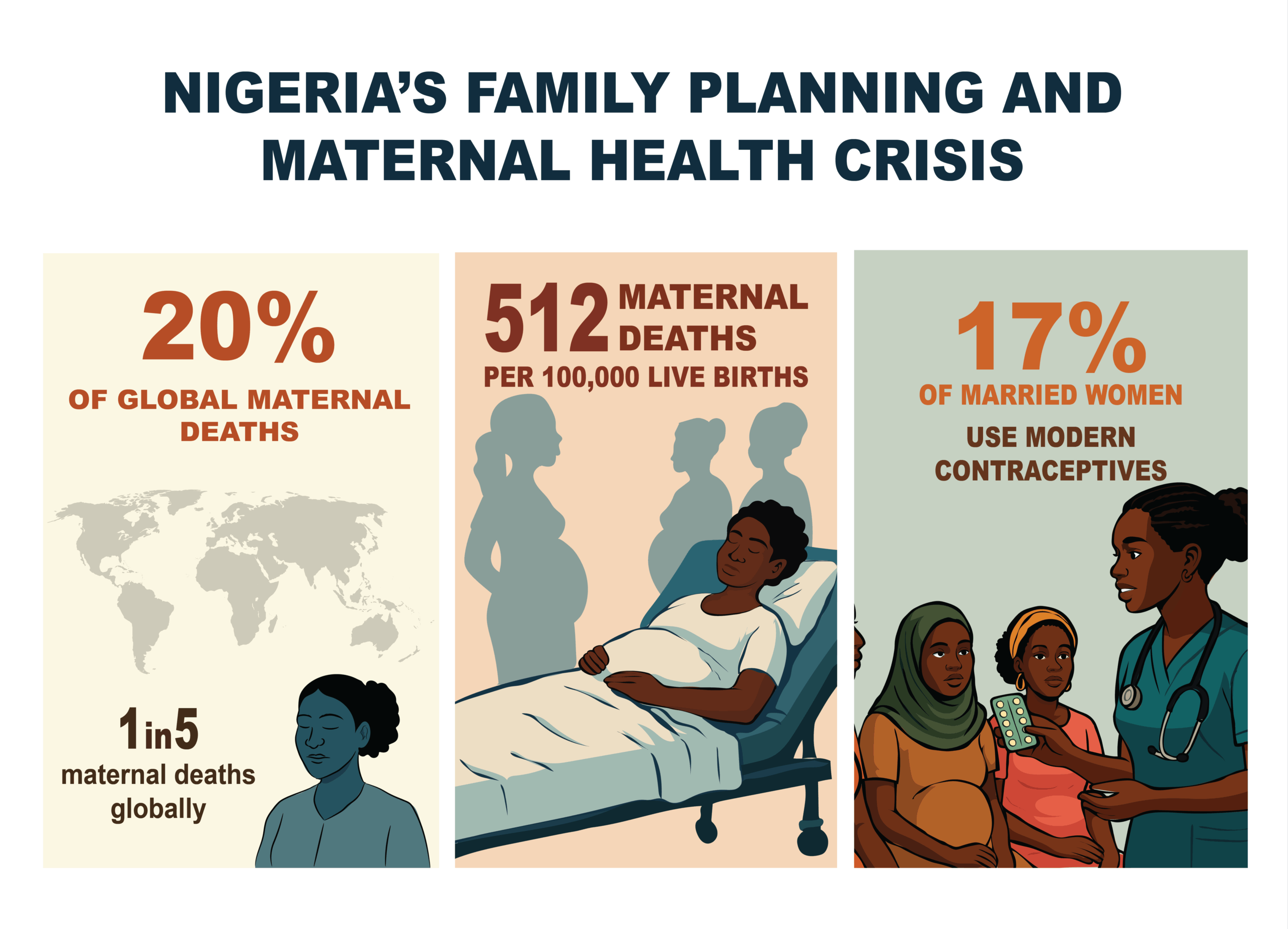

Twenty percent of global maternal deaths happen in Nigeria, with an estimated 512 mothers per 100,000 live births dying from preventable complications. A major silent driver of this crisis is the low uptake of family planning, with only an estimated 12% of married women aged 15-49 using modern contraceptive methods in the country.

Advertisement

In Muslim-majority northern Nigerian states like Niger, cultural and religious norms favouring large families, early marriage, and lower female education often translate into an even higher need for family planning. But women like Hauwa remain vulnerable to unintended pregnancies and unsafe abortions.

EMPATHY DEFIES STEREOTYPES

But amidst these challenges, a local NGO, Youths for Justice Health and Sustainable Social Inclusion (YIJHSSI), is challenging the status quo using empathy to spark behavioural change. Its “Hope for Mothers” project, launched in 2020, proves that in communities where cultural and religious barriers to contraceptives are strong, the most powerful intervention is the simple act of understanding and respecting people’s deeply held cultural and religious beliefs while negotiating the need for contraceptives.

“Before, we focused on clinical access,” said Shedrack Muazu, a women’s health rights advocate and the project’s founder. “But we quickly learned that you can have the best clinic in the world, but if the women are afraid to walk through its doors, or their husbands forbid it, it’s useless.”

Advertisement

The project trained 93 healthcare workers across seven health facilities in empathetic counselling and active listening, helping them understand a woman’s specific fears, concerns, and societal pressures while respecting her autonomy and guiding the conversation towards the benefits of accepting contraceptive options.

“The truth is, women here are constrained by fear and misconception. So, the training taught us to drop the judgement,” Amina, a nurse at the Ungwan Nasarawa Primary Health Centre, said. “We learned to ask, ‘What are your worries? What does your husband believe? How can we support your health and the health of your family?’”

This is particularly powerful during the postpartum period. Many women, weakened by childbirth, are desperate for a respite. So, by integrating comprehensive, empathetic counselling into antenatal care and the year following delivery, Hope for Mothers ensures women receive information and support when they need it most, delivered by a trusted, understanding voice.

WINNING OVER THE HUSBANDS

Advertisement

Many men in northern Nigeria believe that contraceptives encourage promiscuity and cause infertility. So, recognising that educating mothers was futile without their husbands’ buy-in, the project engaged men through carefully planned, persistent dialogues led by community outreach leaders and trained health providers.

“We understood early that we couldn’t bypass the men, and so we had to engage them while respecting their positions as decision-makers and community pillars,” says Muazu, who started the project out of concern about the impact of diseases, poverty, and illiteracy on women and children in rural areas in the north.

Advertisement

Instead of directly advocating for contraceptives, Hope for Mothers reframes the discussion around broader concepts such as responsible parenting, maternal health, child survival, and family well-being. They emphasise that spacing children honours the Islamic values of responsibility and welfare because it allows a mother to regain her strength, ensures healthier children, and improves the family’s economic stability.

Partnering with respected local imams, community leaders, and male elders, discussions are inclusive, with pointers to families doing well due to healthier mothers and better-spaced children.

Advertisement

“Initially, I was skeptical because we were taught that many children are a blessing from Allah,” Hassan Galadima, the mai angwan (community leader) of Ugwan Galadima, stated.

“But the YIJHSSI people sat with us and listened. Then they showed us how a healthier mother can better care for her existing children and how children who are properly nourished and educated become stronger members of the community. They did not tell us to abandon our faith but to understand that responsible spacing is also part of our faith.”

Advertisement

Now, men like Mallam Musa, Hauwa’s husband, are reconciling traditional beliefs with modern health practices. When Hauwa eventually found the courage to speak to Kabiru and invite him to the clinic, she noticed he did not resist. Instead, he attended several empathetic counselling sessions with her.

“Kabiru listened to Musa’s fears about the pills changing me,” Hauwa recalled. “He explained gently in Hausa that family planning means planning, not stopping. He showed Musa how I could be healthier and how our children would do well if I weren’t always pregnant.”

Musa eventually agreed for Hauwa to receive her chosen contraceptive, a decision that has since transformed her life.

Like Musa, 38-year-old Jubril Sanni initially refused to permit his wife to get it. But after participating in a round of discussions, the couple decided they would have just three children. “We want to build a future for them properly,” Jubril said.

The impact of this empathy-driven model is far-reaching. Hope for Mothers directly increased family planning access for over 2,000 women and girls across rural Niger state. The culturally sensitive training for health workers resulted in 25% patient-health facility trust, improving service utilisation.

“Now, when women come to me, they don’t just ask for a method. They share their stories, their hopes,” Kabiru said proudly. “And because I am a male nurse, some of the men bring their wives themselves. But we are gradually building trust.”

THE ROAD AHEAD

Despite its impact, the reach of the Hope for Mothers still represents a fraction of the total need in a state sprawling over 76,469.903 square kilometres of land with nearly seven million people. Expansion to more hard-to-reach villages requires more resources than the self-sponsored project can afford.

Muazu’s efforts to get the state government’s backing have hit brick walls several times, as the authorities often prioritise support to donor-backed initiatives, viewing self-funded ones like Hope for Mothers as less effective, Muazu said. Talatu Abu, the Niger state family planning coordinator, even claimed her office is not aware of the initiative.

Ingrained traditional norms, community resistance in some areas, and the attitudes of some healthcare providers who have not yet embraced the empathetic approach continue to pose more limitations.

“The empathy factor is powerful, but it is also time-intensive and expensive,” Muazu notes. “It requires patience, consistent presence, continuous training, and funding. It is not a quick fix.”

As the sun set over the Ugwan Galadima community, Hauwa’s children laughed as they played, their mother no longer consumed by tiredness but present, engaged, and full of life.

“I still have four children because I realised it was just a pregnancy scare from my delayed cycle,” she beamed. “But now, I have my strength back. I can work on my farm and care for my children without constant exhaustion.”

*Hauwa’s name has been changed to retain confidentiality.

Nigeria Health Watch made this story possible with support from the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organisation dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems (http://solutionsjournalism.org).