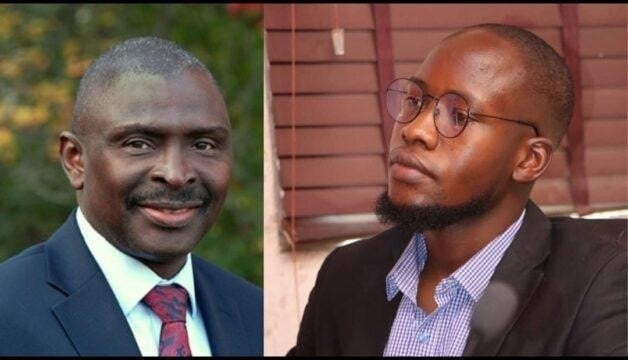

L-R: The ICIR’s Executive Director Dayo Aiyetan and Nurudeen Akewushola.

BY BAMAS VICTORIA

I have spent the last decade in the media, much of it navigating the precarious terrain of accountability journalism in Nigeria. But nothing quite prepares you for the moment your newsroom becomes the headline.

In May 2024, the International Centre for Investigative Reporting (ICIR) was not breaking the news, we were the news. Dayo Aiyetan, The ICIR’s executive director, and Nurudeen Akewushola, an investigative reporter, responded to what the police described as a “fact-finding invitation” at the Nigeria Police Force – National Cybercrime Centre (NPF-NCCC). Accompanied by legal counsel, they entered the facility. Noon came. Then 3 pm, then 6pm. And they still had not returned. Their numbers were not reachable.

This is Nigeria, where journalists cannot walk into police stations without apprehension. Here, the Cybercrime Act – repealed in part but still being wielded – has been weaponised over and over to intimidate the press and other critical voices.

Advertisement

Last year, Femi Falana, human rights lawyer and a senior advocate of Nigeria (SAN), noted that it was illegal for security agencies to arrest journalists for cyberstalking, noting that Section 24 of the Cybercrime Act 2015 which had criminalised ‘cyberstalking’, ‘insult’, ‘causing annoyance’, ‘sending offensive messages’, ‘criminal intimidation’, and ‘causing annoyance’, had been repealed.

During this year’s World Press Freedom Day, editors in newsrooms across the country who spoke with The ICIR highlighted the Cybercrime Act as one of the most dangerous instruments against press freedom.

“Many Nigerian journalists have been arrested by the police on ridiculous charges like cybercrime. What does journalism have to do with cybercrime? asks Chikezie Omeje, the Africa Editor, Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

Advertisement

“The Cybercrime Act has proven effective in stifling press freedom,” adds Aminu Naganye, Editor at WikkiTimes, an outlet that has been repeatedly harassed. At one point, the online newspaper closed its physical office and the publisher, Haruna Mohammed Salisu, was forced to relocate due to persistent threats by the authorities.

The ICIR participated in a media-wide campaign calling for the release of detained journalist Daniel Ojukwu. I helped print the banners on behalf of The ICIR: #FreeDanielOjukwuNow. We marched to Louis Edet House, the Nigeria Police Force (NPF) Headquarters. Ojukwu, a journalist with the Foundation for Investigative Journalism (FIJ), had spent ten days in custody – some of them incommunicado – it was unsurprising when FIJ’s News and Features Editor, Joseph Adeiye, tells The ICIR how vaguely worded laws like the Cybercrime Act are increasingly used to target journalists.

“Revealing stories and accountability reports are often labelled defamatory,” says Adeiye. “Reporters are taken in for weeks or months of unnecessary questioning, all in a bid to intimidate them.”

Back to the police invitation to The ICIR

Working in the media accountability space, we know how quickly these situations escalate. We fear the police’s invitation to The ICIR would.

Advertisement

After six long hours, we issued a press statement about our inability to reach our executive director and the reporter. Finally, Aiyetan was released. But not Akewushola. Perhaps they assume he’ll be easier to break being young, early-career, not yet “battle-worn.” But at The ICIR, we stand by our reporters. So Aiyetan stayed behind.

Eventually, after mounting public pressure and calls from concerned stakeholders, I received a call. It was from the International Press Institute (IPI) Nigeria chapter’s president, Musikilu Mojeed: “Nurudeen has been released on bail.” It was 9 pm.

As the editor, I informed the newsroom and our partners, including civic actors and the press. Those of us who stayed behind finally headed home. But this was only half the battle. Akewushola was shaken by the incident. “I was destabilised for days,” he states. “Overwhelmed by the reality that I could have ended up in prison simply for exposing wrongdoing. The experience made me question how safe journalists are in this country and of course, press freedom generally.”

The toll journalism takes on family and friends is often not spotlighted. The impact of harassment on accountability journalism affects more than just the journalist; it ripples outwards. Akewushola’s family was traumatised. “Seeing them so distressed because of my work added a heavy emotional burden,” he says.

Advertisement

WikkiTimes publisher, Salisu, had once echoed the same, “My work is attracting sorrow to my family, and I worry about them.”

Akewushola had planned to travel home for Eid. He never did. His bail conditions required him to remain available for questioning.

Advertisement

“I had taken a leave so that I would be able to travel home for Eid, but I couldn’t because it’s part of the conditions for my release to be around and come back if they summon me,” he explains.

He learnt something from the ordeal. “It taught me I wasn’t alone in the struggle,” he reflects, “My newsroom, civil society, and other media organisations all stood by me.”

Advertisement

Before the police invitation, the ICIR had published an investigation into police housing fraud. Former Inspector General of Police Solomon Arase, then chairman of the Police Service Commission (PSC), was named in the investigation. He threatened a lawsuit. Corpran Limited, the developer involved, attempted to stop the publication. When the police invitation for questioning came, it was vague. We asked for specifics about the petition. None was given. We suspected the connection. Our sources confirmed it. Aiyetan and Akewushola later did too.

Days later, Arase weaponised his office to announce a lawsuit through the Police Service Commission’s spokesperson, Emeka Ani, a move Aiyetan described as an abuse of office.

Advertisement

“The investigative report that irked Mr Solomon Arase and the lawsuit he purports to have filed [as of then, The ICIR had not received formal notification] are his personal business and have nothing to do with his position as PSC Chairman, and is a blatant abuse of office,” Aiyetan states.

Aiyetan was dismayed that Arase was using the police and its agencies to hound The ICIR, its reporter and editors for a story in which the interest of the police and their property were being protected while noting that the police should be investigating the former IGP instead of “harassing journalists for doing their job.” As such, the ICIR petitioned President Bola Tinubu and asked for his removal. Days later, Arase was removed.

The ICIR is currently in court with Arase, and also the developer, Corpran Limited. This is the other half of the battle. This is not The ICIR’s first brush with Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs). In two years, the Centre has faced at least seven cases. “It’s not because our reports are false – we’re rigorous in our investigations,” Aiyetan says, “but people use lawsuits to punish us. It’s a vendetta. It’s intimidation. They want to waste our time, drain our resources.”

And they do.

“Just two suits – from the same person – one filed in Abuja, one in Lagos, have cost us over N5 million,” Aiyetan reveals. “Without partners helping with legal fees, we wouldn’t survive.” The ICIR has gotten financial support from Media Defence, an international media organisation that provides legal support to journalists, citizen journalists and independent media across the world. It has also gotten other forms of assistance from the Yar’Adua Centre Joint Civic Defence Fund.

The suit in Abuja suit has been dismissed.

Since the Arase suit, the ICIR has received multiple threats of lawsuits. Some have escalated into court cases. The most recent was filed in Kaduna by the Executive Secretary of the National Board for Technical Education (NBTE), Idris Bugaje, following The ICIR’s investigation into allegations of financial recklessness at the organisation.

Legal intimidation is not the only weapon. Sometimes, it’s physical.

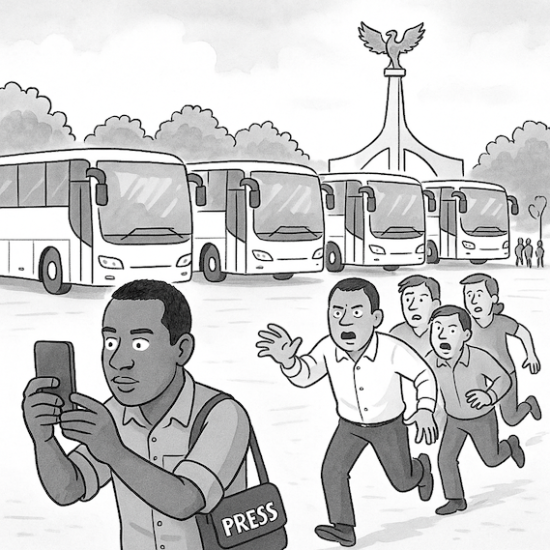

In December 2023, The ICIR’s news editor, Marcus Fatunmole, went to Eagle Square in Abuja to fact-check claims that had gone viral. A video in circulation had claimed that the government was refurbishing second-hand buses to use for a proposed intervention. The video gained traction because of President Tinubu’s promises on June 12 and October 1, Democracy Day and Independence Day, respectively, that his government would procure and deploy high-capacity buses across Nigeria to alleviate pain due to his government’s removal of fuel subsidy.

It should have been a routine verification which included taking pictures in a public space. But he was detained for six hours by the private security guards and police, verbally harassed, threatened to delete the images, and only released after the intervention of civic actors like the Coalition for Whistleblowers Protection and Press Freedom (CWPPF) and The ICIR leadership.

“The experience affected me mentally because I lost my productive time to a baseless matter,” Fatunmole says, while noting that it disrupted the newsroom work for the day. Earlier, in April 2023, The ICIR journalist, Sinafi Omanga, was beaten while discreetly trying to document a case of jungle justice on two men accused of stealing a mobile phone. A man in military uniform and a woman, who identified themselves as soldiers of the Nigerian Army, led the mob action causing him bodily harm.

His eyeglasses were broken, his N5,000 was stolen, and he was forced to pay N4,000 to his attackers, which he did by calling a colleague to make the transfer.

“Upon destroying my eyeglasses, my eyes became the primary target for their punches,” he says. In a separate interview, Omanga spoke about the helplessness he felt at that moment and how it became a defining moment, especially when he noticed a police van passing without intervening.

Even though he got days off, received medical attention and was refunded what was lost by The ICIR, Omanga says, the physical and financial pains are nothing compared to the trauma.

“I became scared of doing my job, especially when it involves the use of a camera. To this day, I still worry about my safety when on the field, especially with a camera. Suddenly, journalism feels so risky to me,” he notes.

Also, in September 2023, the Federal Road Service Commission (FRSC) officials attacked Mustapha Usman, another journalist with The ICIR, while documenting an altercation with a female driver.

“About five of them surrounded and attacked me,” he says. They seized his press ID card and took it to their office, which was nearby. It took the intervention of the Corps spokesperson to get them to release his ID.

These violations of freedom of the press negatively impact journalists, particularly the young or new entrants into the business, as it makes them rethink their career choices and the stories they want to report on.

“The truth is that immediately after the incident, I found myself more cautious and hesitant when covering stories involving law enforcement”, Usman states.

Usman has a fear of law enforcement agencies, particularly the police. He has documented and reported in-depth cases of harassment, “I know how brutal and unprofessional some can be,” he says during a recent interview with The ICIR.

The ICIR’s executive director was not spared from physical assault. On February 25, 2023, during the general election, he was assaulted in Gwagwalada by political thugs. They tore his clothes, stole his phone, wallet, car keys and other documents. Some of these he was able to recover due to the effort of Hamza Sadiq, a chief superintendent of police (CSP) whom he described as “a committed, passionate officer.”

The price of accountability reporting for us has been marked by bruises, blood, legal costs, and mental strain, but there have been allies and support. Saidu Muhammed Lawal, the managing partner of Spectrum Legal Services, which has represented The ICIR on several SLAPP cases, says “SLAPP cases are usually filed by high-ranking public officials who are embroiled in accusations of corruption”.

He adds, “In some cases, there is an effort to get an injunction restraining the civil society organisations from publishing anything in relation to the public office holder even before the case is heard.”

Busola Ajibola, a deputy director at the Centre For Journalism Innovation & Development (CJID), and one of the coordinators of the Coalition for Whistleblowers Protection and Press Freedom (CWPPF), was present when Fatunmole was detained and also during the mediation with FRSC after Usman’s assault. Responding to the question about what justice looks like for the Nigerian press, she says: “Justice means making sure the perpetrators of SLAPPs do not win or get to censor the media. It should be criminal when powerful individuals intentionally set out to censor the press.”

Achieving this, she says, requires a multifaceted approach, including having broader conversations with the judiciary. To this end, Ajibola says CJID has partnered with global organisations, and they give support, which includes reviewing and tightening newsroom processes by pointing out aspects that might leave them vulnerable to SLAPP and other legal threats.

“We are in conversation with the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA) since 2024, the partnership will allow us to seek pro bono support from the public interest litigation arm of the NBA across the country,” she adds.

She calls for a national legal support fund for newsrooms. “We are advocating that newsrooms come together and institute a legal support fund. Something that can be accessed in times of emergency.”

But poor funding has been a challenge for many newsrooms in Nigeria, which Omeje of OCCRP notes constitutes journalism’s major threat. He however, adds that aside from ensuring reports are fair and accurate, newsrooms should also consider insuring themselves against SLAPPs.

Responding to The ICIR question on what kind of support is available to newsrooms facing press freedom violations, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) says, “CPJ’s Emergency Response Team provides financial and non-financial support to journalists following an incident related to their journalistic work. This sometimes includes legal help”.

It adds that the partners with other organisations to help journalists with legal needs and is a member of the Legal Network for Journalists at Risk (LNJAR), which coordinates support to media facing legal threats.

The body, which promotes press freedom worldwide, also notes that “Journalists in Nigeria are regularly prosecuted and face legal harassment for their work. This underscores the need for lawmakers to prioritise reforms that decriminalise defamation and ensure journalism is not criminalised.”

The Nigerian Constitution guarantees press freedom in Section 39, but offers no shield from its consequences. Journalism in Nigeria is like walking a tightrope across a minefield. You never know which report triggers the next lawsuit, the next arrest, and the next beating.

This report was produced by ICIR in collaboration with the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) as part of a project documenting issues focused on press freedom in Nigeria.