I have been following Nigerian club football for close to three decades, and I can tell you without fear of equivocation: it is no longer what it used to be. The quality has dipped, the passion has waned, and—perhaps most damning—the integrity of the game has been steadily eroded by poor management and vested interests at the helm.

Gone are the days when Nigerian clubs like Enyimba International of Aba, Rangers International of Enugu, Iwuanyanwu Nationale (now Heartland) of Owerri, Shooting Stars (3SC) of Ibadan, Super Stores and Julius Berger of Lagos (both, now defunct), BCC Lions of Gboko(defunct), and Udoji United of Awka, were perennial contenders for continental honours. Back then, Nigerian sides were forces in the CAF Champions League and the Winners’ Cup (now CAF Confederation Cup).

Stadia from Ibadan to Lagos, Enugu to Kano, Benin City to Kaduna, Port Harcourt to Jos—everywhere—used to be packed to the rafters. Fans trooped in not just to watch football, but to experience their heroes: the Odegbamis, the Chukwus, the Amesiamakas, the Okallas, the Atuegbus, the Ojebodes, the Keshis, the Owolabis, the Okochas, the Taribos, the Finidis, the Kanus. Mentioning those names turned an ordinary match into a carnival.

Today, an average Nigerian football fan may not even know the reigning NPFL champion, or the highest goal scorer from last season. That disconnect is the direct outcome of a league plagued by poor play, weak packaging, and compromised integrity.

Advertisement

It has been over 20 years since Enyimba won Nigeria’s last continental title (CAF Champions League, 2003/04 & 2004/05).

In the past decade, Nigerian clubs have struggled to even scrape into the group stages of CAF competitions, let alone make a real impact. Contrast that with the meteoric rise of Morocco’s Wydad, Raja, and RS Berkane, or South Africa’s Mamelodi Sundowns—teams that now stand toe-to-toe with Africa’s traditional giants like Egypt’s Al Ahly and Zamalek, and Tunisia’s Club Africain and Espérance. The gulf in class and consistency could not be more glaring. Nowhere has it been more glaring to me, than the recently concluded, CAF Confederation’s Cup 1st preliminary round match, between Kwara United and Asante Kotoko.

So, how did we arrive at this sorry pass?

Advertisement

1. Poor Technical Foundation: The First Touch Problem

A footballer is only as good as his first touch. This basic skill should be mastered at the grassroots. Sadly, many of our players struggle to trap or shield the ball, losing possession under the slightest pressure. This is because they were never taught at the early stage of their career. Too often, NPFL players are seen controlling the ball with the wrong parts of their body (shin or knee), killing momentum and gifting the opponent an advantage.

Compare this with countries like Spain, Brazil, Germany, or even Morocco and Egypt, where ball mastery is drilled into players at academy level. Until Nigeria fixes this at grassroots and coaching-institute level (notably the Nigerian Institute of Sports), we will keep producing technically deficient footballers. Our teams will continue to look inferior to their peers across the continent.

2. Lack of Cohesion: Eleven Players, Eleven Islands

Advertisement

Nigerian teams often play like 11 disconnected units. Off-ball movement is poor, team chemistry non-existent. Coaches and fans then pin all hopes on one or two players to dribble coast-to-coast and score—a fantasy in modern football.

The result? Predictable, disjointed, kick-and-follow football. No fluidity, no pattern, no identity. I watch the two legs of Kwara United and Asante Kotoko, both in Accra and Abeokuta, and I think I am strongly positioned to offer an insight. The Nigerian team never looked like they’ve ever trained together before the match. It was like the players met themselves at the Kotoka International Airport for the first time, and from there, they agreed to come and play the match. Contrast that with Asante Kotoko, who knocked out the team in Abeokuta last weekend, winning the home and away (4-3 in Accra, and 1-0 in Abeokuta). The Ghanaians could close their eyes, and string passes together seamlessly, moving crisply as a unit, while the Nigerians banked on flashes of individual brilliance that were easily smothered.

Football is a team game. Its beauty shines when passes flow telepathically: think Barcelona’s Xavi–Iniesta–Messi triangle, Madrid’s BBC (Bale, Benzema, Cristiano), or Arsenal’s Henry–Bergkamp–Pires–Vieira quartet. That chemistry is what Nigeria has lost.

The seamless understanding that once existed between the strike force of Rashidi Yekini, Yakubu Aiyegbeni, Julius Aghahowa, and Victor Agali, and the creative brilliance of midfield generals and wingers like Sunday Oliseh, Nwankwo Kanu, Jay-Jay Okocha, Finidi George, and Emmanuel Amuneke, produced the thrilling moments that powered Nigeria to the 1994 AFCON glory and a historic World Cup debut. That same telepathic connection is what today’s attack — spearheaded by Victor Osimhen, Victor Boniface, Tolu Arokodare, and Sadiq Umar — still struggles to find with midfielders and wingers such as Alex Iwobi, Samuel Chukwueze, Frank Onyeka, Wilfred Ndidi, Chidera Ejuke, Raphael Onyedika, and Ademola Lookman.

Advertisement

3. Rudderless Identity

Every great footballing nation has a style: Brazil with Jogo Bonito/Samba, Spain with Tiki Taka, Italy with Catenaccio, Argentina with La Nuestra, Germany with their machine-like efficiency, France with athletic flair, England with their traditional kick-and-rush.

Advertisement

Nigeria once had an identity: the 4-4-2, blending wing play with a dominant midfield, laden with creativity. That style gave us fluidity, and goals. Today, our play is directionless—predictable long balls, no invention. Even Osimhen, one of the most lethal strikers in Europe, often looks stranded for the Super Eagles, starved of service, and forced to drop deep.

4. Corruption in Recruitment

Advertisement

Merit has been sacrificed on the altar of connections. To get into a national camp, a player often needs more than talent—he needs a godfather, a recommendation note, or cash to “grease” palms. Agents exploit this by mortgaging young players’ futures.

This rot is not limited to the national team. At club level too, “man-know-man” trumps merit. As a result, we churn out mediocre squads that can’t compete beyond our borders. It’s no surprise that both Kwara United and Abia Warriors crashed out of this year’s CAF Confederation Cup on the same day. As Remo Stars prepare to face Memlodi Sundown, South Africans on social media are already throwing jibes over how ordinary they will make the Nigerian champions look, over the two legs.

Advertisement

The Broader Consequences

Even war-torn Sudan hammered Nigeria 4–0 at the 2024 CHAN tournament. That humiliation should have been a wake-up call. Instead, we keep deluding ourselves with clichés about “going back to the drawing board.” As Chief Donatus Agu-Ejidike quipped after Kwara United’s elimination: “Are we sure the drawing board will still be waiting where we left it? Other nations have moved forward; even the board itself may have moved ahead.” The inherent point was not lost in the satirical remark from the Anambra-born Sports philanthropist.

The Way Forward

Nigeria’s crisis is not talent deficiency—it is structural failure. We need:

A Stakeholders’ Summit: Not a jamboree of rent-seekers, but an assemblage of ex-internationals, proven coaches, seasoned sports journalists, and administrators with vision.

Footballing Identity: Nigeria must decide on a modern style of play—infuse it into grassroots, academies, and national teams at all levels.

Grassroots Reform: Coaching institutes must prioritize fundamentals: ball control, off-ball movement, tactical discipline.

Meritocracy in Recruitment: Only the best should don club and national jerseys. Period.

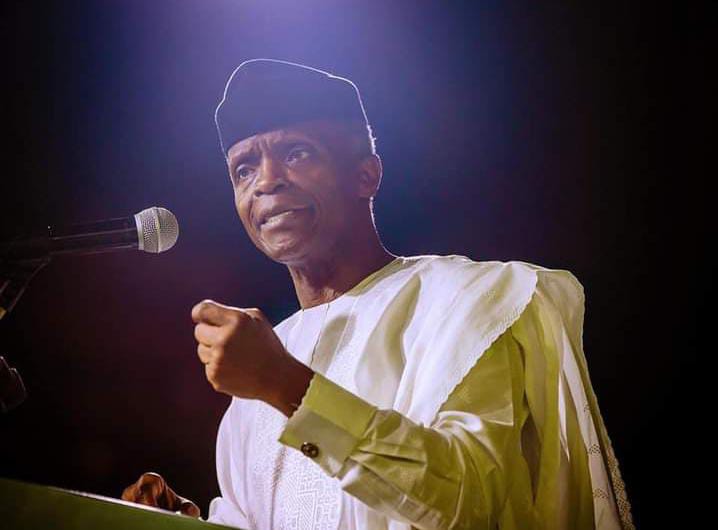

The likes of Segun Odegbami, Austin Okocha, Kanu Nwankwo, Mutiu Adepoju, Adegboye Onigbinde, Ikẹ Shorunmu, Kunle Soname, Michael Emenalo, and Seyi Olofinjana—people with knowledge and credibility—should be central to such a summit. Even the current Chairman of the National Sports Commission (NSC) Malam Shehu Dikko could be involved. Football is no longer a pastime. It is a multi-billion-dollar industry that can transform lives and nations. It has gone beyond being a mere PR tools for the political elite. It is business and should be so treated.

Unless we recalibrate urgently, we risk being permanently overtaken by so-called “smaller” African nations who are already miles ahead in planning, discipline, and execution.

Abubakar writes from Ilorin, Kwara State. He can be reached via 08051388285 or [email protected]

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.