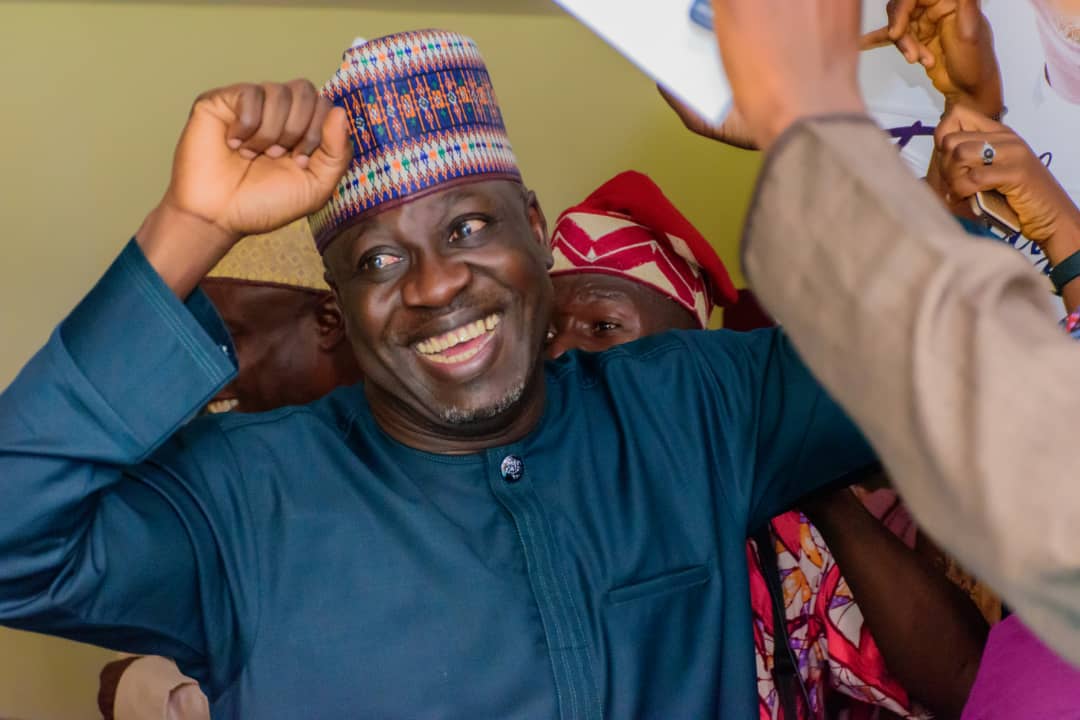

Women of Owukpa. Photo credit: Vivian Chime

Ibagwa is a community in Owukpa, Ogbadibo LGA of Benue state. Owukpa is a coal-rich area with mining activities going on in different communities — and Ibagwa is one of them.

Owukpa Consolidated Mines Nigeria Limited, a coal exploration, development and mining company, established in 2003 has been mining in the community since 2007. But in the past year, things have changed as the company which has been mining coal for over a decade in the community downed tools and fled.

Julie Okoh, a member of the community and a climate activist, was instrumental in the company’s sudden exit from the community. In 2014, Okoh began creating awareness using social media on the land degradation and health challenges being experienced in her community as a result of coal mining.

“Coal mining became a doom not a blessing to my community because there is no drinking water, there is no hospital, the children are suffering deformity and malnourishment, infertility became a norm. And so I rose up against it,” Okoh said.

Advertisement

Okoh added that the more reason why she stood against the miners was that as a climate activist, she knows that “climate change is real, environmental degradation by exploration of fossil fuels is real,” and her community was feeling its devastating impacts.

Before the company’s exit, protests in the community gathered momentum such that protesters began getting arrested and harassed. This led to the arrest of Okwori Onaji, another environmental activist from the area in July 2020.

At this point, Okoh decided that more needed to be done to forcefully stop the miners from entering the community. And so in August 2020, she mobilised women in her community to rise up against the activities of the miners.

Advertisement

Failed promises fuel women’s agitation

To this effect, the women began meeting weekly to devise means of sending the coal miners out of their community. Part of their agitations was that the coal mining company had promised the community basic amenities like water, schools, and healthcare centres but never stayed true to their promise. And yet, the community is made to suffer the consequences of the mining.

On the company’s website, it clearly stated its core values to include: the value for lives and well-being of indigenes of the area of operation and the development of the society it operates in. But none of this is true for Owukpa.

The road leading to Owukpa remains untarred, sloppy and littered with gullies. The vegetation on both sides of the road can be seen to be dying off and farmers are no longer able to go to farm due to degraded and unproductive lands. And despite its safety policy, Owukpa Consolidated Mines Nigeria Limited located its mining site a stone’s throw away from the only secondary school in the community. This led to physical cracks on the walls of the school and the breaking down of the school buildings.

Advertisement

“This is the only secondary school that this community has but this is where they [the coal company] deposit and load their coal,” Okoh said.

“This is where our children read, they read amongst coal, they eat coal, they drink coal, they read coal, because when you are in school the debris falls as they are blasting, the sound from the mines is so devastating. The vibration shakes down the walls.”

She said the unkept promises were the major reasons for the community’s resistance because the coal mining company “kept saying we will do it, we will do it. So in 2020 we said if you are not doing it, please leave”.

Speaking in the same vein, Maria Onoja, a woman in her early 80s and the mother of the village chief, said the women took the initiative to block the roads and send away the miners because they could no longer bear the polluted water, degraded farmlands and sicknesses that the community suffered as a result.

“We blocked the roads to prevent further coal mining because we are dying due to pollution from the coal mining activities,” Onoja said.

Advertisement

“Our health is threatened. There is no water, our roads are completely eroded. We cannot transport our farm produce to the market due to the terrible state of the road. We and our children have become prone to illnesses due to the mining activities.”

Women invoke deity against coal mining company

Advertisement

As protests by the women continued for 14 days nonstop from morning to night, the women (old and young) also began receiving threats of arrest if they did not end the resistance.

Rose Idoko, a farmer, recalls how during the protest, “they wanted to fight us, they said they would call the police, they threatened to do all sorts but we did not fear because this is our land. No police will come and arrest us for something that is happening in our community”.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, Okoh said the major backup which gave the women courage to continue the resistance was the community deity. The women, amid the threats, invoked Ibagwa’s deity of justice, an age-long local gong called Ekwanya, which sits in the community’s shrine and is respected by community members for its power to bring death on anyone perverting justice.

“Even those that were supporting the miners, as soon as they heard we had invoked the deity, they took off their hands. Because the deity does not come out ordinarily, the women brought out the priestess of the deity to make proclamations and it worked for us,” she added.

Advertisement

It has been over a year since the women invoked the deity that caused the coal miners to abandon their tools and flee the community. Okoh said the diety’s curse is still in place and that is why “up till now, we have not seen them”.

How long can the resistance be sustained?

However, for someone like Idoko, she said the women will continue to hold back the coal miners from entering the community until “they give us roads, hospitals, water, electricity and school because we need our children to be educated”.

“We need them to help us because as we are now in the village, we do not have anything to do because the farmlands are no longer productive. Our cassava and other crops are getting rotten yearly when we cultivate. So we don’t have anything to do,” she lamented.

But Okoh is worried, because according to her, in as much as she understands the climatic impacts of coal mining and would rather it ends in her community, she doubts if the resistance can go on for long if the people are not empowered. She said she fears that if the coal mining company eventually meets the community’s demands, they might succumb.

“The ability to stand for resistance is when there is help. If there is no help, you can’t sustain resistance,” she said. “If I say don’t take coal, I must bring something to sustain my resistance and when I am poor, you give me anything, after a while, I won’t be able to sustain resistance.

“So, I am asking, whatever we need to do, we need to do it. We must sustain the people, we must empower the people. A people that is not empowered can be enticed with bait.”

Mike Terungwa, team lead at Global Initiative for Food Security and Ecosystem Preservation (GIFSEP), said this is a major challenge facing climate action in communities. He said the government needs to provide basic amenities for communities to be able to adapt, adding that civil society organisations also need to stand up to the challenge.

“The government needs to provide basic amenities, not just to the fossil fuel-dependent communities or the host communities but to everyone around the world,” he said.

‘No more coal mining in Ibagwa’

The stories of the indigenes are not different from what is obtainable in coal mining communities around the world.

Coal is known to be the dirtiest fossil fuel because it is the most-carbon intensive when burnt, adding to the global climate change issue. Its terrible impacts on the health of people and the environment were the reason countries committed to phasing out coal at the 2021 COP26 in Glasgow. But this decision was compromised at the last minute — from phase-out to phase down.

In 2020, developed countries failed to meet their pledge of providing developing countries with $100 billion per year to support climate action. At the last COP, the countries said the finance will be available in 2023 instead.

As countries prepare for COP27 in Egypt, people like Okoh and the women in her community are seeking help for the survival of their people, so as to be able to resist coal mining activities. But for now, the women of Ibagwa in Owukpa remain resolute in their stand that there would be “no more coal mining in Ibagwa”.

This report was first published by Our Climate Impact