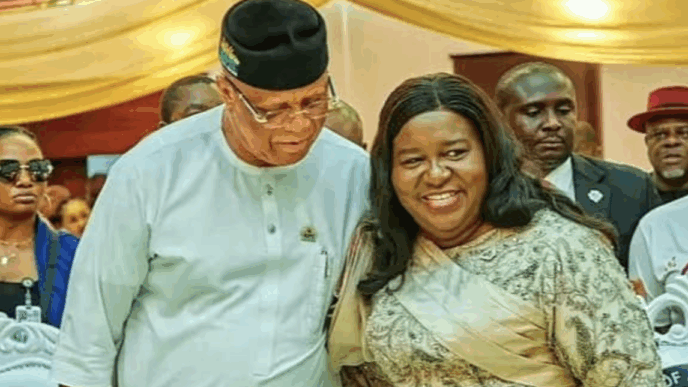

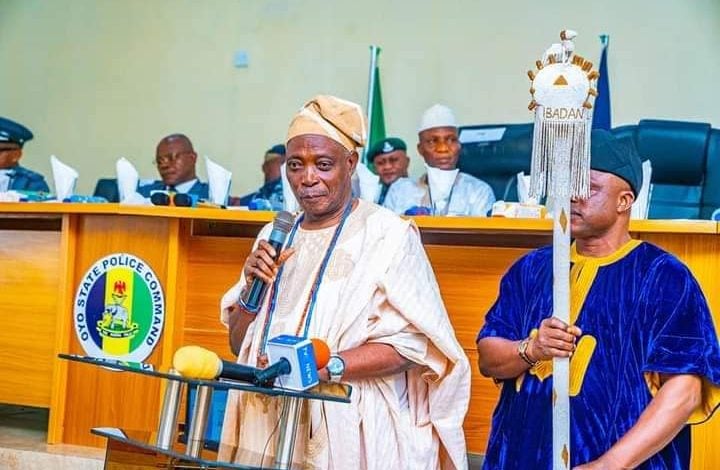

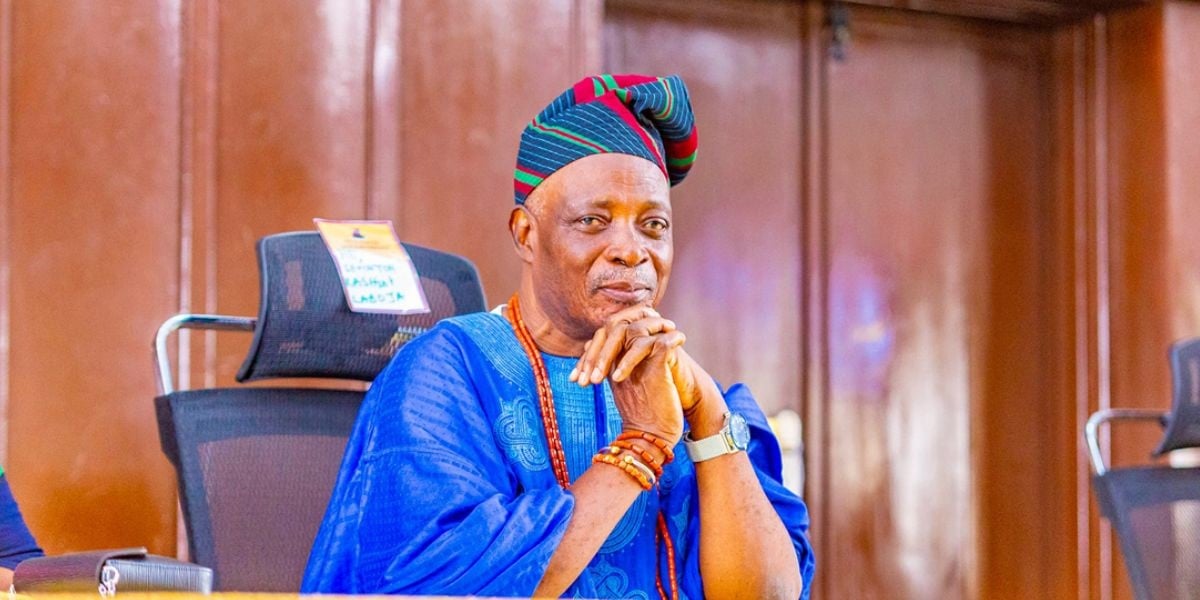

Rashidi Ladoja, Olubadan of Ibadanland

He was born a king-in-waiting, like every Ibadan-born male child. The royal blood flowed with a rhythm of uncertainty in his throbbing veins as he ascended the mogaji ladder from jagun to otun Olubadan.

It would eventually take 81 years for the probability to become reality. In the ancient brown-roofed city, for a king to be made, a king must die. With the death of Owolabi Olakulehin, Ladoja, the highest-ranking chief in the civil line, is historically favoured to take the throne as the 44th Olubadan. Thirteen months ago, Ladoja made a decision that prepared him for this moment. But in those eight decades of waiting, Ladoja was many things.

He was born on September 25, 1944, in Gambari, a community just outside Ibadan, nestled between Ogbomoso and Ilorin. It was the hometown of his paternal grandmother, a widely respected and influential trader. Ladoja recalled his mother’s account of how, thanks to his grandmother’s standing in the community, his naming ceremony turned into a grand celebration that lasted three days. The Fulani community gifted his mother a cow, which was slaughtered for the occasion, and a musician was brought in from Ilorin to entertain guests. People came in droves, bearing yams and other food items as gifts. Before his birth, Ladoja’s mother had a son named Rashidi, who passed away just days after his naming ceremony. From birth, Ladoja was celebrated as a child befitting kingship.

He had his primary education at Life Mission School, which later became Ibadan Progressive Day School, Alaadorin. He attended Ibadan Boys High School and later Olivet Baptist High School. After completing his secondary education, Ladoja received a scholarship from the Belgian government, which enabled him to pursue his childhood dream of becoming an engineer. He earned a degree in chemical engineering from the University of Liège in Belgium in 1972.

Advertisement

Remarkably, four months before graduation, he had already secured a position with Total Oil. Since he spoke French fluently, he was employed in Paris, but he chose to work in Nigeria. Ladoja spent 13 years with the company before resigning in 1985 to explore opportunities in private business. By the time he turned 40, he had already become a millionaire.

‘ANKARA AMBASSADOR’ DRAGGED INTO POLITICS

At the time, Ladoja was in Lagos when Busari Adebisi and Omololu Olunloyo approached him in 1991 to ask if he was interested in joining politics.

Advertisement

“Over my dead body,” he replied, and told them he preferred to remain in business, though he maintained a keen interest in politics back home and was curious about the aspirants. That conversation marked the beginning of what he later described as being “dragged into politics”.

But politics wasn’t entirely unfamiliar terrain for him. His father had once served as a councillor when all of Ibadanland was a single local government area.

Known for his simplicity and strong ties to Yoruba culture, Ladoja has long made Ankara fabric his signature attire — a sartorial choice that has become synonymous with his identity, and an extension of his grounded, culturally rooted persona. He traced his fondness for ankara to a trip he once took with Obasanjo to the Benin Republic, where the president was praised by their hosts for wearing the traditional fabric. The moment left an impression, and ankara became Ladoja’s go-to attire.

Ladoja often recalls how his political journey formally began in 1991, when Dejo Raimi persuaded him to support Kolapo Ishola’s bid for governor.

Advertisement

“…I said that is good. Then he phoned and within minutes, Chief Ishola was there. We extended pleasantries and Raimi now said this is Ishola, who is contesting governorship on the platform of SDP. I want you to support him. I said no problem and I asked, what can we do to assist you? The day he met me, he was looking at me and thinking, this man that is wearing ‘Ankara dansiki’, where is he going to get money for me,” Ladoja said.

In a 2021 interview, when asked why he wore Ankara and chose a simple lifestyle over that of affluence to reflect his wealth, Ladoja asked, “Is my Ankara not clean?”

When Ishola became governor, Ladoja offered him advice on the need to make water publicly available for residents, proffering a solution to a dilemma that had long troubled Ishola.

“So, he said we have got the solution. He called somebody and said as from tomorrow, start reconnecting the water. I want to meet all the local government chairmen. He said ‘and we have been begging you to join politics and go to the senate. After all, it is not going to jeopardize your business’. That was how I agreed. That was how I became a politician,” Ladoja said.

Advertisement

After that, Ishola introduced Ladoja to Lamidi Adedibu, a political godfather in Oyo, and thereafter, he was propelled to take the form for the senatorial election.

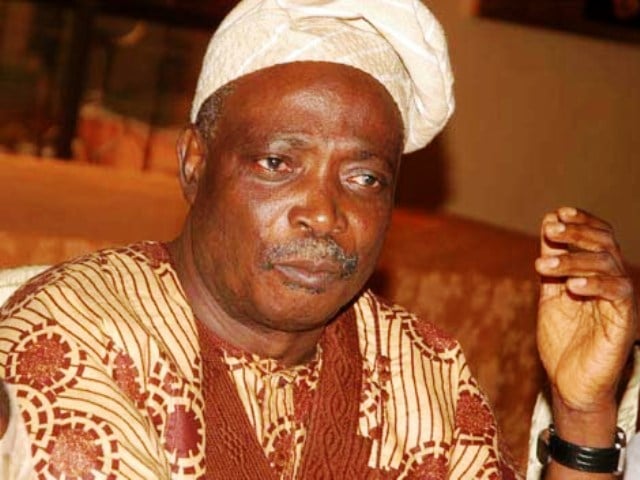

THE FALLOUT WITH ADEDIBU AND IMPEACHMENT SAGA

Advertisement

Rashidi Ladoja’s foray into national politics began during the brief life of Nigeria’s third republic, when he was elected senator representing Oyo-south on the platform of the Social Democratic Party (SDP). A decade later, in 2003, he successfully contested the Oyo state governorship election under the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), with the influential Adedibu backing his candidacy.

However, the alliance between both men was short-lived. Shortly after assuming office, Ladoja fell out with Adedibu over disagreements, particularly around the allocation of government appointments. The fallout set the stage for one of Nigeria’s most talked-about political crises.

Advertisement

On January 12, 2006, 18 out of the 32 members of the Oyo state house of assembly impeached Ladoja. His deputy, Adebayo Alao-Akala, was swiftly sworn in as governor. Ladoja, however, challenged the impeachment in court. In November 2006, the court of appeal in Ibadan declared the process null and void, though it urged all parties to await the supreme court’s final ruling.

Three years later, in a landmark judgement, the supreme court upheld the appeal court’s decision, reinstating Ladoja as governor on December 12, 2006. He became the first Nigerian governor to be returned to office through a court verdict, a legal precedent that would later benefit others, including Peter Obi of Anambra state and Joshua Dariye of Plateau state.

Advertisement

Reflecting on the episode, Ladoja described his reinstatement as his “finest hour”, not just personally but for Nigeria’s democratic evolution.

“Lawyers will continue to quote it for life in Nigeria,” he said, expressing pride in having confronted the system and won.

He also accused then-President Olusegun Obasanjo of orchestrating the impeachment, alleging it was in retaliation for his refusal to support Obasanjo’s controversial third-term bid.

After completing his term in 2007, Ladoja’s bid for a return was cut short when he lost the PDP primaries to Alao Akala, his deputy. He subsequently stepped down from the governorship race.

He made another attempt in 2011 and also failed to secure the PDP ticket.

He later contested the 2011 and 2015 governorship elections under the Accord Party but lost both times to late Abiola Ajimobi.

Beyond electoral politics, Ladoja was a key figure in the National Democratic Coalition (NADECO), the pro-democracy group that opposed the annulment of the June 12, 1993 presidential election. His involvement forced him into exile in the UK during Sani Abacha’s military crackdown on activists. He did not return to Nigeria until after Abacha died in 1998.

Ladoja acknowledges President Bola Tinubu as one of the people who provided him support in those moments.

In recognition of his quiet but firm role in Nigeria’s democracy struggle, the Research Centre for Integrity Assessment and Evaluation (RCIAE), in 2023, honoured Ladoja with the ‘Unsung June 12 Hero’s Award’.

CASE WITH EFCC

Ladoja’s impeachment trial did not end with his reinstatement.

On August 28, 2008, he was arrested by the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) over allegations of siphoning and laundering N4.7 billion from the coffers of the Oyo state government.

He was briefly remanded in prison by the federal high court in Lagos on August 30, 2008, and was granted bail on September 5, in the amount of N100 million with two sureties for the same sum.

Ladoja was charged alongside Waheed Akanbi, a former commissioner for finance in the state.

In March 2017, Adewale Atanda, a prosecution witness, told the court in Lagos that Ladoja purchased 22 cars for lawmakers in 2005 to evade impeachment.

The EFCC closed its case against the accused in September 2018, and the 11-year trial came to an end in 2019 when the court discharged and acquitted Ladoja. The court held that the evidence brought against Ladoja and Akanbi was “too low on credible evidence”.

FOUNDED A BANK ‘OUT OF ANGER’

After stepping back from active politics at the end of his senate stint, Ladoja shifted his focus to business, venturing into real shipping and pioneering the construction of ships tailored for specific projects.

“We collaborated with a Norwegian company to build vessels suited to the Warri terrain, and that marked the beginning of several business successes,” he said.

Frustrated with the service from their banker at the time, Ladoja and his friend, Z. Babule, decided to start their own bank. This led to the founding of Crystal Bank of Africa, which eventually became insolvent.

In 1997, the struggling bank was acquired by Tony Elumelu, who renamed it Standard Trust Bank (STB).

Ladoja became a director at STB in 2000.

According to Elumelu, STB became one of the five largest banks in Nigeria before its merger with United Bank for Africa (UBA) in 2005.

He described the acquisition as the breakthrough that launched his rise in the Nigerian banking industry

CHALLENGED OLUBADAN CHIEFTAINCY REFORMS

In 2017, Ajimobi conferred the title of obaship on some high chiefs and baales, giving them the right to wear beaded crowns and coronets and be addressed as “his royal majesty”.

But Ladoja, who is one of the 11 high chiefs who stood to benefit from the pronouncement, resisted the move, arguing that it violated the 1957 Ibadan chieftaincy declaration.

Ladoja insisted that as the chiefs are successors to the Olubadan throne, they cannot be crowned twice.

He took the matter to court, and the legal battle went beyond Ajimobi’s tenure to that of Makinde, causing a delay in the appointment of Olalekan Balogun.

In June 2023, Makinde signed the chieftaincy amendment bill into law following its passage by the state house of assembly.

He subsequently approved the promotion of the 11 Ibadan high chiefs to be crowned obas.

Under the amended law, the 11 high chiefs, who form the Olubadan-in-council, were recognised as the traditional heads of the 11 LGAs in Ibadanland. Ladoja was the only chief who rejected the obaship and was absent at the coronation ceremony.

In July 2023, Ladoja approached the Oyo state high court in Ibadan to challenge the promotion of his fellow high chiefs to the status of obas.

Among other demands, Ladoja sought a court declaration that the elevated chiefs, having accepted kingship titles, were no longer eligible to ascend the Olubadan throne.

However, when the case was scheduled for hearing in October 2023, the presiding judge, Justice M.O. Adegbola, recused himself and directed that the file be returned to the chief judge for reassignment.

Citing potential bias, Adegbola explained that his close relationship with Ladoja and some of the defendants could raise questions about judicial impartiality and integrity.

There was no official information confirming whether Ladoja has continued with or withdrawn the case, and when Olakulehin was to be crowned following Balogun’s death, there were speculations that Ladoja might take up the matter again.

In August 2024, after seven years of resisting the reform, Ladoja finally bowed to pressure and accepted the Oba title.

Since the amended chieftaincy law only recognised oba-in-council, not chief-in-council, it could jeopardise his ascension to the throne since he was already Otun Olubadan and next in line.

Speaking on why he changed his mind, Ladoja said if his refusal to accept the beaded crown would affect his ascension to the throne as Olubadan, he would accept it in a ceremonial capacity.

EXECUTIVE PRODUCER

Lights, camera, action!

Ladoja is as unpredictable as he is versatile. Beyond politics and business, his deep appreciation for culture and its preservation found expression in the world of film. He played a quiet but significant role in the production of some of Tunde Kelani’s classics, including “Oleku”, the timeless romantic Yoruba film released in 1997.

In 2024, Kelani stirred nostalgia and curiosity when he tweeted a photo of Ladoja on set, revealing that a new film chronicling the former governor’s life was in the works.

A MAN WHO ‘DOES NOT PANIC’

Few can withstand the kind of trials Ladoja has faced and still remain influential across history, politics, and business. His calm demeanour in the face of adversity has become part of his legacy.

In 2014, at age 70, Ladoja confidently declared that he was still fit, both mentally and physically, to govern Oyo state. Even during the tense period of his impeachment, he said he remained composed, with his blood pressure steady at 110/70.

“Age is in the mind. I believe so much in God that anything I want, He will do it for me. I don’t frustrate myself, and I do not panic. At 70, my blood pressure still remains 110/70,” he said.

More recently, Ladoja spoke of his ambition to ascend the throne as Olubadan, again citing his enduring good health as a sign of divine grace.

“By the grace of God, I will become Olubadan. God has been merciful to me. My blood pressure has been stable,” he said during an appearance on Agbami Oselu, a political programme on Fresh FM.

“Anyone God has destined to become Olubadan will become Olubadan — no matter the obstacles placed in their way.”

WITH LADOJA, ‘THERE IS ALWAYS ROOM FOR EXCELLENCE’

In 1957, when Ladoja took the entrance examination of Ibadan Boys High School, he saw that the parents of other candidates came in “big cars”.

He told his father, who had no car, that the wealthy parents could influence their children’s admission.

“My father said ‘don’t worry; there will always be room for excellence’, and it paid out,” Ladoja said.

He later took the entrance examination for Olivet. However, he was unable to pay the acceptance fee on time due to lack of funds.

When he finally gathered the money and went back to the school, he was informed registration had closed. But when the principal asked of his name and found out he was the candidate with the best result in the examination, an exception was made for Ladoja.

“They normally would take 25 pupils in a class, but they had to make an extra space for me to be the 26th person in the class,” he said.

Again, his excellence paid out, and “there is always room for excellence” became his watchword.

At the time he was awarded a scholarship to study in Belgium, Ladoja had also secured admission into Ahmadu Bello University to study mechanical engineering, as well as another offer from the University of Lagos for electrical engineering.

“When the opportunity of Belgium came, I went there to study chemical engineering. All along, you would see that there is room of excellence,” he said.

When Total offered him a job, Ladoja delayed his resumption — not out of hesitation, but because he wanted to attend the Olympics in Germany. He had earned that kind of freedom, basking in the privilege of merit and confidence in his future.

Engineer. Senator. Businessman. Governor. King

It would be nothing short of the truth to say that Ladoja has lived a life full of chapters, each defined by ambition, principle, and defiance.

Kabiyesi o.