The deserted villages of Southern Kaduna where only the brave dare reside | TheCable.ng

Abandoned homes, deserted compounds, and desolate communities are, nowadays, common scenes in parts of southern Kaduna. Insecurity-fuelled fear has forced many residents — mostly women and children — to find abodes in saner climes. In many of the attacked communities, only courageous men dare stay back and spend the night. Every man has now become a vigilante while their wives and children are scattered across the safe(r) parts of Kaduna.

DESERTED AND DESOLATE

Owing to past attacks and threats of future return, several villages are now bereft of residents. In Gonan Rogo, many houses are desolate and abandoned. The area paints the picture of a once-lived village. The attack there was so deadly that a nursing mother and her newborn were said to have been killed in their home. Their compound is slowly being overtaken by weeds while clothes of mother and child are stacked in sacks in a room that appears to be the sleeping quarter. Shards of glass scattered on the floor and a crack in the window of the mud-brick house represent a reminder of the horror that played out there.

“Only a few people remain in this village. Majority have run away,” Simon Kakuri says as he recounts the details of the initial and subsequent attacks. “For the past three days, they have been coming to attack this village. We have not been sleeping. We have not been finding it easy with these herdsmen. Even if we farm, their cows will eat our crops.”

Advertisement

During the day, the women of Gonan Rogo temporarily return to cook for the men who have refused to run away but instead, guard the village while bearing the inclement conditions of camping in the bush and sleeping in the open.

“Whether it rains or not, we have no choice but to sleep outside. Throughout this rainy season, we have been sleeping in the bush,” he adds.

Although there have been no attacks in recent weeks in Makuti, a community in Gan Gora, Zangon-Kataf LGA, majority of the women and children have failed to return home after fleeing when they were hit in July. Where houses stood now lie ash-adorned, unlivable structures. Amos Tokan, the community leader in Makuti, says certain properties were targeted, owing to the haphazard pattern of destruction.

Advertisement

Zipak, a small community in Jema’a LGA which was attacked on July 24, is now home to many standing ruins. The once vibrant compounds have become relics housing charred spring beds, unrecognisably burnt television sets, and dismembered wheelchairs — all slowly getting rusty as the rains gain free access to them through the roofs which were once covered but are now torn apart as a result of the fires.

The women and children of Zipak have been forced to flee their homes, with some camped at the IDP camp in Zonkwa. Given the events of July 24 and subsequent warnings, only the brave dare remain in Zipak. “They say they are coming back but we don’t when,” Anthony Luka, the community leader, says in a defeatist tone.

LIVING ON HANDOUTS

Husseina Usman wears her heart on her sleeve. Intermittently, she bows her head to wipe tears effortlessly running down her face. Having lost three members of her family — mother and two brothers — she can’t help it as her emotions betray her.

Advertisement

Originally from Kwaku in Zangon-Kataf, Husseina now resides in a single room in Danpami, Marere, Lere LGA, alongside her husband and nine children.

“We were in our house preparing breakfast when we saw them coming,” she said of her attackers. “We were unable to take anything from the house. We trekked in the bush for three days.”

During those three days, Husseina’s husband was frantically scouring the bush in search of his family. When they reunited, the family made its way to Danpami. With the level of violence she witnessed, Husseina says she has no intention of returning home. The only thing paramount on her mind is how to feed, clothe her children, and secure better living conditions.

Advertisement

The Jafaru family which has Zainab Yusuf, 55, as its matriarch also grapples with the same challenges after losing everything when Kurmin Gandu was hit.

Following the attack, they travelled for two days in the bush without food or water until they arrived at a settlement in Laduga, where they now live on handouts. Not less than 53 people reside in their settlement which houses six thatched huts.

Advertisement

‘PEOPLE WERE LEFT TO THEIR FATE’

Most residents of southern Kaduna are full-time farmers. It is their main source of employment and income. Whether Adara or Fulani, farming is the way of life here. Maize, groundnut, ginger, and rice are among the major agricultural produce in southern Kaduna. Planting starts in May and harvesting is usually between October and November.

Advertisement

When the COVID-19 pandemic reared its head, the planting season was hit hard as many farmers could not go to the market to purchase farm inputs as a result of the regulations which restricted movement and transportation. Those who were able to move around found that the prices of seedling and fertilizer had increased beyond what they could afford.

As soon as persistent attacks and killings became the order of the day, things got worse than anticipated. The insecurity in southern Kaduna also contributed to the spike in prices of maize, which all but crippled the poultry industry until the government recently stepped in. Livelihood suffered a huge blow as many were not able to plant while those who planted were unable to tend to their crops. Due to the inability to go to the farms and the destruction of their crops, 2021 is expected to be a difficult year for many southern Kaduna residents. Already, many female farmers are helpless, with no produce to sell and no income coming in.

Advertisement

According to Reverend Waziri Gambo, pending when the insecurity abates and they are able to return to their farms, they will need to start small businesses to feed their children. “We wish we could empower them to start something because they are not working. But we can’t help without financial support.”

That is where social advocates and human rights crusaders like Alheri Bawa Magaji of Resilient Aid And Dialogue Initiative (RADI) come in.

Alheri is the daughter of Bawa Magaji, an Adara Wazirin who was incarcerated without charge alongside nine elders of the Kajuru traditional council for over 100 days in 2019. That incident thrust Alheri into advocacy for the disenfranchised, less privileged, and particularly displaced persons in her native southern Kaduna.

“I didn’t know these things were happening until my father was arrested.”

Her advocacy started on Facebook, where she often solicited funds for displaced persons in need of hospital care, empowerment or resettlement.

“I realized more and more that people were left to their fate.

“We have given fertilizers to over 50 farmers, we have empowered over 50 widows. If you give them food, in three days, it is gone, so are you going to keep feeding them? We decided to go into empowerment. We also train them in funds management and business management.”

CAN’T FARM, CAN’T RETURN HOME

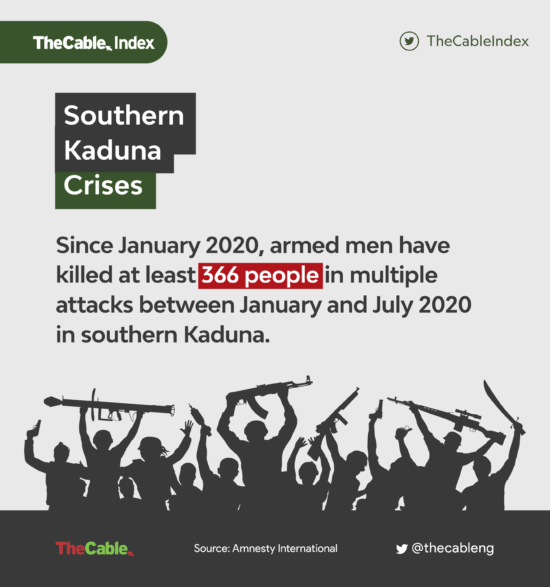

There is no doubt that there is a humanitarian crisis in southern Kaduna as many communities have been permanently displaced.

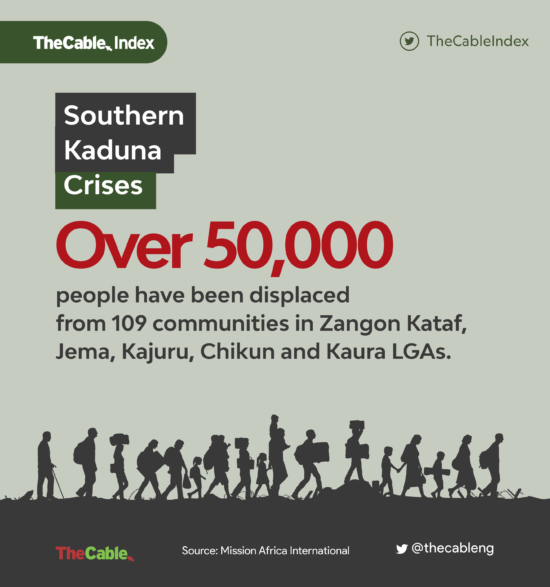

According to Mission Africa International, over 109 communities in Zangon Kataf, Kauru, Kajuru, Chikun and Kaura have been living in permanent displacement with over 50,000 people living either in recognised IDP camps or with relatives.

Rebecca Joseph from Kibori says her children have refused to go back home “because what they saw is very terrible”. Since the attack, she has been in the Mercy IDP camp with three of her five children. Her husband stayed back to protect the village with other men.

During the attack on Chibob, Hannatu Micah witnessed the horror of her child being shot in the leg, hand, and chest after which his hand was hacked off in one fell swoop. Her brother-in-law was also shot and burnt in the room where he was killed.

Margaret Ishaku says the people of Kigudu had been living in harmony with the Fulani herdsmen until July when things changed. In Margaret’s presence, her stepfather and his in-law were burnt alive.

Hence, she was forced to flee and find abode in Mercy IDP camp, run by Reverend Waziri, who works for the Evangelical Church Winning All (ECWA).

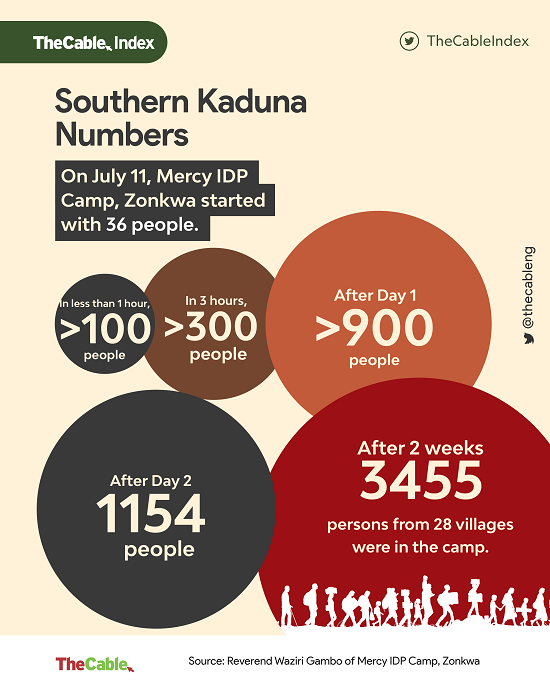

On July 11 after the attack at Chibob and Sabon Kaura, Waziri sought permission to start the camp “when 22 persons were killed and their families had to run for their lives”. To underscore the spate of displacement, he said the initial members of the camp were 36 but “in less than one hour, the number of people increased to over 100. In two, three hours, we were over 300”.

Continuing, he said: “When we understood that women and children were inside the bushes, we hired buses and trucks to go into the bushes and bring them. We finished this exercise around midnight. That day we had around 900 people in the camp. The following day, it increased to 1154.

“After another attack, the number increased to 2416. After two weeks, we had 3455 people in the camp. All the classrooms were filled up. We had 80-100 people in one class.”

According to the Reverend, the camp has housed displaced persons from 28 villages and no less than 5000 people have been helped thus far.

“Our major challenge is where they will go after the camp because some houses were burnt. We are praying and thinking of raising something for them to rebuild their burnt houses.”

To this, Alheri Magaji says it is only when the conflict is put to bed that people can start to rebuild their lives from scratch.

“Beyond the crisis, what we really want to do is empower our people. The crisis keeps taking us away from building ourselves. It is taking us further backwards.”

Although the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) says it has provided relief materials to two camps in Kajuru and Zonkwa LGAs, the displaced women and children appear to be in critical need of sustainable intervention. Beyond periodical food supplies, the displaced women yearn to find a means of livelihood so as to support and feed their children on a daily basis.

A recommendation to provide empowerment intervention has been made to the management of the agency and is pending approval, says Abanni Imam Garki, zonal coordinator, Northwest Zone, NEMA.

But how long that approval will come to fruition remains to be seen.

‘SAFETY NOT GUARANTEED IN SOUTHERN KADUNA’

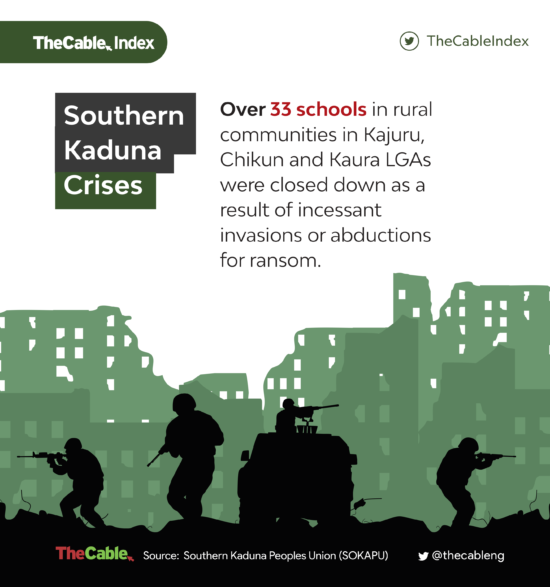

According to the Southern Kaduna Peoples Union (SOKAPU), over 33 schools in rural communities in Kajuru, Chikun and Kaura LGAs have closed up since the 2020 crisis reared its head.

In spite of the ongoing dialogues and peace pacts signed by some communities, insecurity is still widespread — killings and abductions still persist.

These abductions and killings continue despite the presence of security operatives in some parts of southern Kaduna.

Community leaders of Makuti in Zagon-Kataf, Zipak in Jema’a, and Kukum Daji in Kaura LGAs have lamented that the security operatives deployed to their areas are insufficient and incapable of repelling the attacks, should they occur.

When asked about the security situation in areas within the Zonkwa axis, Rev. Waziri noted that “some places are ‘safe’ because ‘safe’ in southern Kaduna is not guaranteed”.

And without the guarantee of security, the process of reconstruction and rehabilitation cannot begin, says the north-west zonal coordinator of NEMA.

‘TRUTH, JUSTICE & FAIRNESS’

This inability to facilitate adequate security is one of the chorused shortcomings of the Kaduna state government. This criticism has emanated from various quarters with many locals also echoing them. They say the state government’s body language does not inspire confidence.

Awemi Dio Maisamari, national president, Adara Development Association, recently accused the Kaduna government of “reeling out rhetoric while their actions and inactions serving as encouragement are speaking loudest”.

When asked to react to the criticism and comment on the uneasy security situation in Kaduna, Samuel Aruwan, commissioner for internal security, referred TheCable to the Defence Headquarters. Multiple efforts to get a response from the Oyema Nwachukwu, DHQ spokesman, proved futile.

Commenting on the security situation, Alheri Magaji panned the Nasir El-Rufai-led Kaduna government and local authorities for allegedly trying to cover up the humanitarian crisis in the state.

She said: “Every time people want to come and help, the state government and the local government will say there is nothing going on.

“As a local government, I think a lot of help would have come to these people if the chairman will accept and agree that there is a problem.”

Reverend Waziri echoed Magaji’s sentiments, noting that “people are putting pressure on us from different angles because they don’t want the camp to exist”. Asked to expatiate, he said there is a possibility that “they don’t want the media and the world to know. They don’t want people to know our plight”.

Waziri went on to lay emphasis on the fact that “only truth, justice and fairness” can resolve the hydra-headed, multi-narrative, complicated land-related conflict that has resulted in gruesome acts of violence and displaced society’s vulnerable persons. But pending when the recommended trio-solution sees the light of day, what becomes of the vulnerable women and children of southern Kaduna?

You can read the first part HERE.

Watch the full documentary below.

This is a special investigative project by Cable Newspaper Journalism Foundation (CNJF) in partnership with TheCable, supported by the MacArthur Foundation. Published materials are not views of the MacArthur Foundation.

Add a comment