The first week of COP30 ended on a cautious note on Saturday, with negotiators reporting slow progress despite a new draft text that, for the first time, formally elevates “just transition” in the climate talks.

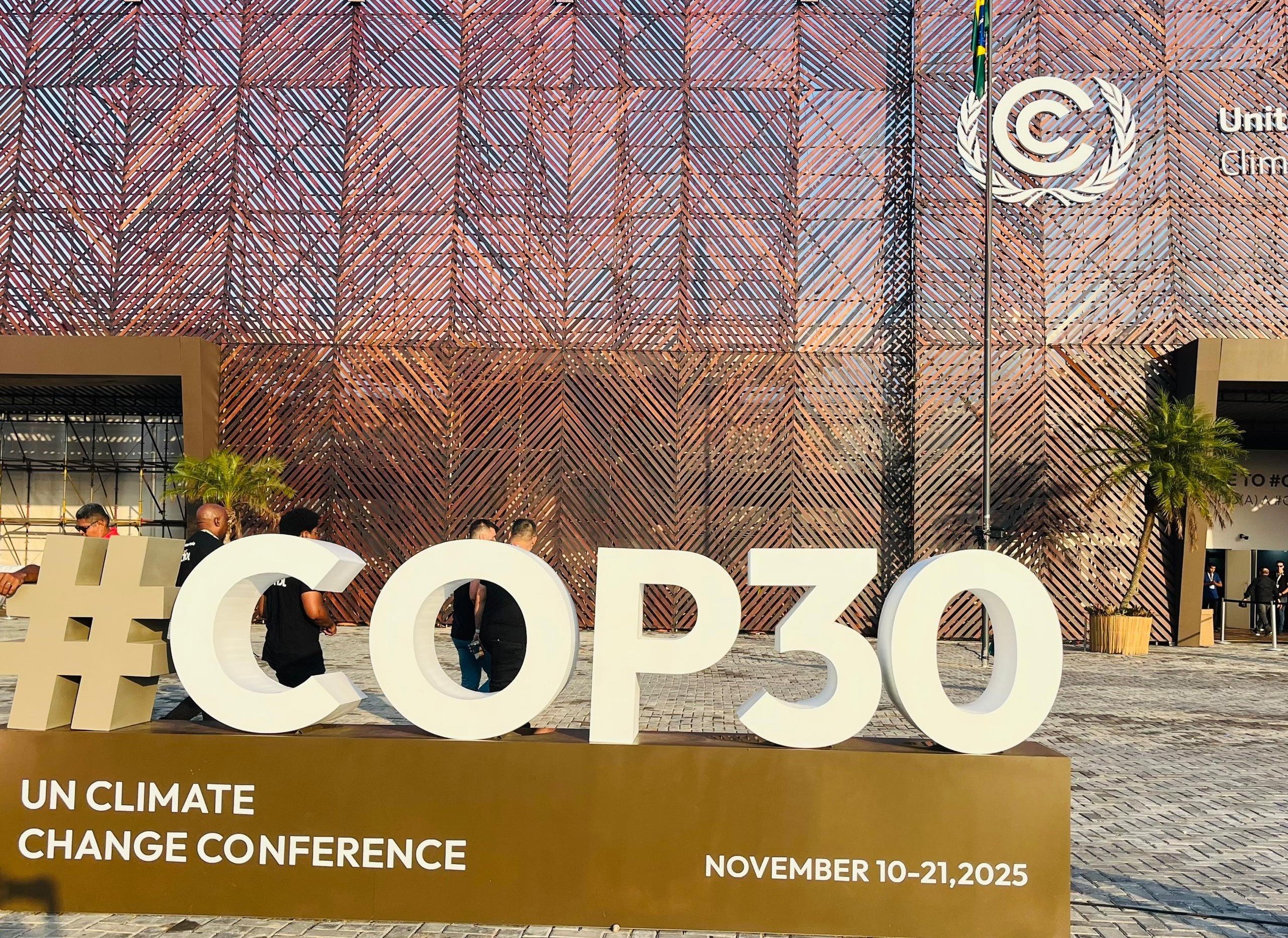

On the opening day of the UN climate conference in Belém, Brazil, COP30 President Andrea do Lago defused a potential early standoff by urging countries to delay debates on contentious issues on climate finance, carbon border measures and data transparency.

The move helped avert the agenda fights that have derailed past summits, but it did little to hide deeper tensions simmering underneath.

Advertisement

Tensions flared on Tuesday when a group of indigenous demonstrators attempted to force their way into the venue, prompting security officials to temporarily shut the gates.

Protesters demanded stronger recognition of indigenous rights and land protections in the negotiations, exposing long-standing frustrations that frontline communities remain sidelined despite Brazil hosting the talks on Amazonian soil.

A MILESTONE DRAFT

Advertisement

By Friday, as the high-level segment continued into its first week, negotiators released a draft text that for the first time recognises a formal just transition mechanism — the most notable development so far.

The proposal, known as the Belém action mechanism (BAM), frames just transition as a process requiring finance, technology transfer, workforce development and social protection.

It signals growing acceptance that the shift to cleaner energy must be fair and must not deepen historic inequalities.

For many developing countries, particularly in Africa, the recognition is long overdue. With demand surging for critical minerals used in electric vehicles, batteries and other clean technologies, African delegates warn that the transition risks repeating old extractive patterns — where resources leave the continent while communities are left with environmental damage, low-skilled jobs and little economic value.

Advertisement

Kudakwashe Manjonjo, energy adviser at PowerShift Africa, described BAM’s inclusion in the draft as “a milestone”.

“This is the first time we’re seeing clear written language on a just transition mechanism at COP,” Manjonjo said.

“The Global South is not coming empty-handed. The minerals needed for the transition are in the Global South, and we are offering solutions.”

He added that a global framework must protect small businesses, cooperatives and informal workers who “drive adaptation at the ground level”.

Advertisement

African negotiators insist that BAM must include safeguards against exploitation, equitable value chains and financial support for countries facing economic disruption as fossil fuel industries wind down.

The African Group of Negotiators (AGN) has repeatedly stressed that the continent cannot transition without predictable and adequate financing.

Advertisement

DIVISIONS DEEPEN OVER ADAPTATION INDICATORS

Beyond the breakthrough on just transition, the sharpest divide in week one of the summit was in the negotiations on the ‘global goal on adaptation’ (GGA).

Advertisement

Delegates are narrowing down a list of adaptation indicators to about 100, which will help countries measure progress in building resilience. But at least 16 remain red lines for developing countries.

Developed nations favour standardised, quantifiable metrics tied to national planning and reporting systems, while developing countries argue that such metrics ignore capacity constraints and shift responsibility onto nations that lack the finances and technology to deliver.

Advertisement

Richard Muyungi, AGN chair, said Africa rejects indicator frameworks “that expect developing countries to do more with less”.

“Some indicators place responsibilities on developing countries without providing the means to act,” he told journalists. “They must reflect real needs and come with real support.”

African negotiators are calling for a two-year policy alignment process before the indicators are adopted, allowing countries time to refine and assess their implications. Developed countries want immediate adoption.

Amy Gilliam-Thorpe, programmes manager and adaptation lead at PowerShift Africa, warned that several indicators “shift responsibility to developing countries and infringe national sovereignty”.

“Indicators on private finance and national budget allocations unfairly place the burden on vulnerable countries,” she said, adding that week two must deliver “quality adaptation finance and a coherent framework linking national adaptation plans, transparency reports and the global stocktake”.

Finance remains the dividing line across all negotiating tracks. African delegates reiterated that developed countries must meet obligations under article 9.1 of the Paris Agreement, which requires them to provide financial resources.

They also raised concerns that blended and hybrid finance models “camouflage commercial terms” and could worsen debt rather than ease the transition.

Trade measures such as the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) and new forest regulations were flagged as potential forms of green protectionism that could hurt African economies.

“When Africa emits the least globally, penalising isolated sectors without considering development contexts is unjust,” the AGN chair said at a media briefing on Friday.

Still, observers say week one proceeded more smoothly than expected.

Iskandar Vernoit, executive director of the IMAL Initiative, noted that the presidency “avoided a contentious agenda fight” and has kept channels open for consultations on issues raised by different blocs.

But experts warn that without deliberate policies, the global energy transition could deepen inequality.

Fossil-fuel-dependent regions face job losses, while many developing countries risk being excluded from green opportunities due to limited finance, technology and workforce capacity.

As COP30 enters a decisive second week, negotiators now face difficult questions: who will finance the just transition mechanism, how will it be governed, and what accountability tools will ensure equity?

The fate of the GGA indicators remains uncertain. The challenge for the presidency will be whether early diplomatic calm can be converted into meaningful progress at a summit expected to deliver on ambition.

This report was produced with support from Sahara Group and the Kaduna state government.