Eligible voters checking for their names on the wall before an election in Nigeria | File photo

BY LEKAN OLAYIWOLA

Now, as we look to 2027, civil society is taking an early stand. The Nigeria Civil Society Situation Room has issued a Credibility Threshold — a landmark framework built on six integrity benchmarks and seven guiding principles. It calls for a truly Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), a sanitised judiciary, reformed political parties, and meaningful civic engagement. It is bold. It is necessary.

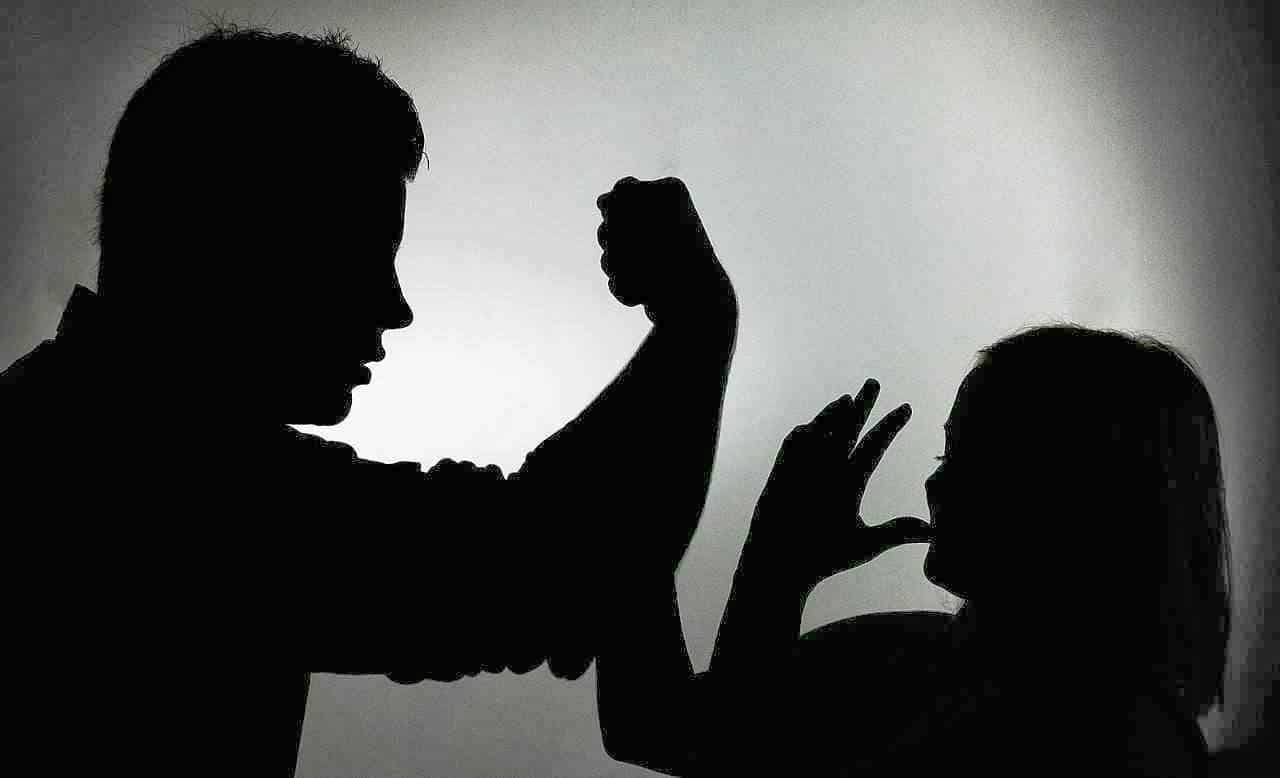

But if 2023 taught us anything, it is that rules alone don’t save democracies. Cultures do. Despite all of the hope invested in new technologies like BVAS, and for all the promises of integrity and reform, we still had real-time transmission failures, brazen voter suppression, judicial rulings that prioritised technicalities over truth and historic voter apathy (only 27 percent turnout in a country of 200+ million people).

Why the 2023 reforms failed

Advertisement

Civil society organisations have, for decades, sounded the alarm early. Yet none of these thresholds truly held. Why? Nigeria didn’t suffer from a lack of frameworks. It suffered from a deficit of institutional empathy and the absence of an ethical and relational transformation in how we build trust, power, and participation in Nigerian democracy, which opened a vacuum where trust, restraint, and moral accountability should have lived.

The problem wasn’t that reforms were not proposed. It’s a power never intended to be lost. A ruling class reliant on voter suppression, cash-for-delegates, and selective prosecution will not be moved by appeals to procedure alone. It is the presence of entrenched power networks that benefit from failure.

A political class addicted to patronage, selective justice, and electoral manipulation has no incentive to democratise itself. In 2023, this class exploited legal ambiguity, institutional weakness, and public fatigue to protect the status quo. Until reforms confront the calculated resistance of those who profit from chaos, they will remain little more than aspirations. Thus, the Credibility Threshold isn’t enough, and that is where a complementary civic vision is urgently needed to change the outcome in 2027.

Advertisement

A shift from checklist to culture, from rules to rituals

We’ve been conditioned to think that effective political discourse must sound combative, complex, or overly technocratic. But we now need a different kind of power grounded in moral courage, emotional intelligence, and civic design. And that unsettles people because it refuses to play by the rules of fear or jargon.

While the Credibility Threshold sets technical standards, we must now plant civic rituals. This isn’t just about strengthening INEC’s servers or amending legal language. It’s about teaching public actors how to listen, and giving citizens the tools to speak in ways that power cannot ignore. How do we do that?

We should explore structured civic architecture in a practical and repeatable way rooted in lived experience:

Listening hubs and responsiveness index pilots

Advertisement

We begin by creating spaces—physical and digital—where citizens voice electoral harm, memory, and expectation, especially in areas notorious for electoral malpractices or violence. These become repositories of civic trust, where public officials are trained to hear not as technocrats, but as custodians of dignity.

In partnership with civil society, we measure how institutions perform on inclusion, care, and civic responsiveness. These assessments will serve as early mirrors for reform, helping institutions improve behaviour before elections, not just after.

Restraint protocols for power

Real deterrence requires more than courts; it demands public shaming, institutional exclusion, and cultural isolation of those who sabotage the system. Electoral offenders should not return to public office as heroes or dealmakers. They should be stripped of access to platforms, contracts, and legitimacy. Social institutions: churches, mosques, universities, unions etc must help set these boundaries.

Advertisement

Trust literacy in schools and streets

We prioritise focus on people, not just processes. We shift voter behaviour not just through awareness campaigns, but through cultural instruction in self-governance. We seed narrative modules in schools, town halls, and faith communities—teaching dignity, voice, and restraint as democratic skills.

Advertisement

Civic education should no longer be a one-way broadcast of deadlines and slogans. Instead, we must build emotionally intelligent voter engagement—through storytelling, art, radio dramas, and school curricula that connect democratic participation with dignity, healing, and shared struggle.

Institutional co-creation

Advertisement

Coalitions are not enough without a coordinated strategic plan. Reform groups must cultivate inside–outside pressure, working with progressive legislators, legal watchdogs, and electoral officials while organising citizen-led protests, strategic litigation, and regional monitoring hubs.

This is not merely advocacy. It’s a peaceful disruption, forcing an unaccountable system to either adapt or be exposed. This isn’t a third-party watchdog approach. It’s a civic covenant. These frameworks are co-designed with electoral agencies, security forces, and civic educators—building ownership, not outsourcing responsibility.

Advertisement

Will 2027 be any different?

Why did reforms fail in 2023? They fell short because they asked institutions and political actors to behave better without first retraining their instincts for care and building the kind of ethical reflexes that make dignity the default, not the exception, during election cycles.

The stakes in 2027 are not abstract. If Nigeria repeats the mistakes of 2023, we risk more than another flawed election; we risk democratic collapse cloaked in constitutional order. When fewer than 10 million people decide a president in a country of over 200 million, legitimacy is no longer real; it’s only managed.

This vacuum invites voter withdrawal, disinformation, military adventurism, and the erosion of public faith in the idea of the republic itself. Reform must now be treated not as an option, but as a firewall against civic decay. If democracy must be reborn in 2027, it will not be because rules got sharper, but because power remembered how to listen—one ritual, one relationship, one institution at a time.

Let the Credibility Threshold be the line Nigeria draws in the sand. But let ethical deterrence be the wind in our lungs when we say that we won’t just count votes; we’ll count voices. We won’t just protect procedures. We’ll protect the dignity of the process and participants.

Lekan Olayiwola is a peace and conflict researcher and practitioner. He can be reached via [email protected]

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.