I have spent the last few years making sense of Nigeria through numbers. From my early days at StatiSense to heading TheCable Index and now leading insights at SBM Intelligence, data has been the constant thread connecting my work. Across all these roles, one thing has remained clear to me: data tells the truth that people and politics often try to hide. But lately, I have been asking a different question: who really owns Nigeria’s data?

We like to say that data is the new oil. It sounds good in conferences and strategy sessions. Yet, unlike crude oil, which sits under the ground and officially belongs to the state, data does not have a clear owner. It is scattered across government agencies, banks, telecom firms, social media platforms, and even the devices we carry around every day. Every click, transfer, or hospital visit produces new information about us, but very few Nigerians know who controls it or how it is used.

Take a simple example. The other day, I went to visit a friend in one of those estates on the Island in Lagos. At the gate, I was asked to fill out a register. On that sheet were spaces for my name, phone number, address, and the name of the person I came to see. That is valuable data sitting in the hands of a security guard. Your phone number alone can be used to build a marketing list, and when combined with your name and location, it becomes even more powerful. If that register ends up in the wrong hands, or if the guard decides to sell the contacts to a company that wants to send bulk SMS messages, how would I ever know?

I have seen companies copy numbers from WhatsApp groups and upload them directly into bulk messaging platforms to promote new products. These things happen quietly, every day. Our personal information is constantly being collected and reused without our knowledge or consent.

Advertisement

The same issue exists on a larger scale. When you register for a SIM card, your biometrics are captured by both your network provider and the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC). The NCC says it is for security and identity management, which makes sense. But what happens when that information is shared with other agencies or private firms? In most cases, there is no requirement for consent, no easy way to check who has your data, and no real avenue to opt out.

Banks also collect huge amounts of data about our spending habits, income levels, and locations. E-commerce platforms track what we buy and when we make purchases. Government agencies gather information through BVN, NIN, and voter registration. These databases rarely speak to each other, yet all of them speak about us. And in a country where institutions are weak, data privacy is often treated as an afterthought.

The creation of the Nigeria Data Protection Commission in 2023 was a welcome step, but laws alone are not enough. Enforcement requires technical capacity, independence, and political will. When data breaches occur, how many institutions face real consequences? When citizens’ details leak online, who do we hold responsible? Too often, nobody.

Advertisement

Meanwhile, foreign companies make billions from the data of African users. Facebook knows your interests, Google knows the routes you travel, and TikTok can tell your mood from the videos you watch. These platforms harvest local data to power global algorithms, yet the benefits rarely flow back to the economies generating the information.

Imagine if Nigeria treated data with the same seriousness it gives to oil. If we refined it locally through strong data centres, transparent policies, and local analytics capacity, we could create jobs, strengthen industries, and make better decisions. Instead of importing insights from Silicon Valley, we would build our own intelligence grounded in our realities — from mapping food insecurity to tracking migration patterns or improving revenue collection.

At SBM Intelligence, we use data to decode government policies and economic trends. But the biggest challenge is not always analysis; it is access. Important datasets are hidden, delayed, or incomplete. When data is treated as a secret rather than a national resource, the entire country loses. You cannot solve what you refuse to measure.

So yes, data may be the new oil, but Nigeria has not decided whether it wants to export raw numbers or refine knowledge. The difference lies in ownership. Whoever controls the data controls the narrative, the policy, and, ultimately, the future.

Advertisement

Until we treat data governance as a national priority — not just a digital talking point — we will continue to lose value. Our information will keep enriching others while we remain consumers of insights about ourselves. And perhaps that is the real tragedy: in a country overflowing with data, Nigerians still do not own their own story.

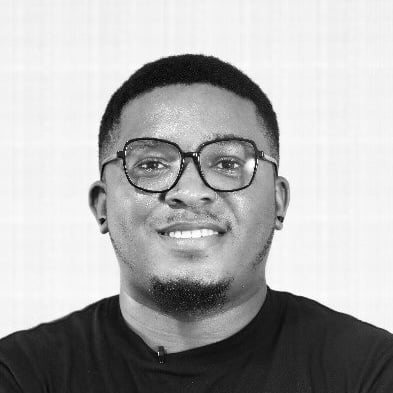

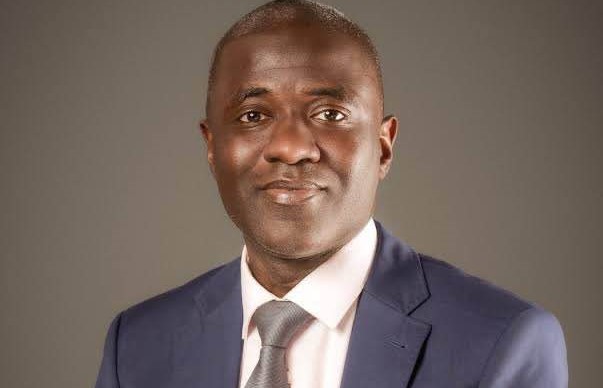

Victor Ejechi is the head of insights and storytelling at SBM Intelligence.

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.