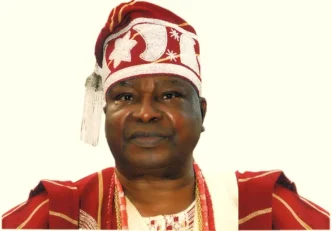

Uzodinma: We are all guilty of not doing enough to preserve the natural habitat we met

From a distance, Imo State can appear like a tangle of contradictions. Ask around, and you’ll hear everything: “It’s all going downhill,” “Things are getting better,” “I’m not sure anymore.” These narratives vary wildly depending on who’s speaking, what they’ve experienced, and what they choose to see.

But here’s the thing: distance distorts. From afar, it’s easy to judge, easy to label, and even easier to misunderstand. The real story, the deeper motivations behind what governments do, only becomes clearer the closer you get or dig beneath the surface.

Of course, public policies often appear as bundles of actions—new programmes, schemes, and projects launched by governments in response to visible needs. But beneath these actions lie ideas, and beneath the ideas lie values. These values may not be immediately visible, but they give policies their shape, tone, and long-term meaning. In the case of Imo State, a closer look at some of its key current initiatives reveals a more profound coherence: not necessarily in their structure or delivery mechanisms, but in the ethical vision that binds them.

A good entry point for this conversation is the Imo State Health Insurance Scheme, which aims to enrol 2.7 million people. At face value, it is a policy intervention to improve healthcare access. But more fundamentally, it is a social statement. It reflects a belief that certain life needs should not be left to the randomness of personal income or geographic luck. In a society where many people still rely on prayer and chance to deal with medical emergencies, the introduction of a public health insurance scheme communicates a clear ethical stance: no one should have to choose between life and livelihood. That statement emerges from a worldview in which healthcare is not a privilege but a right, where solidarity is extended to the most vulnerable through shared financial mechanisms. At its core, the health insurance scheme represents a commitment to social protection, equality of life chances, and the dignity of the human body.

Advertisement

The same value of dignity and the structures that support it show up in the One Kindred One Business Initiative (OKOBI) programme, albeit in a different form. On the surface, OKOBI is a community enterprise model aimed at economic inclusion through kinship-based business development. Over 400 OKOBI businesses have already been launched, involving more than 11,000 people. Some are in agriculture, some in processing, some in small-scale manufacturing. However, what makes it conceptually interesting is not just its method but the moral intuition behind it. OKOBI assumes that people already possess something valuable—their relationships, networks, cultural cohesion—and that development should begin by building on these existing assets. This runs counter to the often technocratic logic of development that views rural communities primarily as sites of deficiency. OKOBI sees them as sites of potential. Its value orientation leans towards agency, ownership, and local wisdom. It doesn’t aim to parachute solutions from above; instead, it recognises that communities, when organised around shared purpose and supported with the right tools, can become engines of their own prosperity. That worldview is not accidental. It reflects a deep trust in people and in the ethics of participation.

SkillUpImo, a digital skills development programme with a target to train 300,000 youth, belongs to a more modern, tech-forward policy domain. But even here, the underlying values connect seamlessly with the others. The initiative speaks to a future-focused understanding of equity that recognises that digital literacy is becoming a new form of social power. In this sense, SkillUpImo is not just about jobs or coding bootcamps but about capacity. It acknowledges that inequality is not just about income gaps but also about knowledge gaps, and that if young people are not equipped with relevant skills, they risk being structurally excluded from tomorrow’s economy. By placing tens of thousands of youths on a path of skill acquisition, the programme articulates a belief in both individual potential and collective progress. It frames Imo’s youth not as burdens to be managed, but as co-creators of the state’s future. That is a powerful value statement—one grounded in hope, fairness, and a belief in the transformational capacity of learning.

Taken together, these three programmes reveal a more philosophical than political pattern. They are concerned about fairness, not as abstract rhetoric but as operational logic. In different ways, they seek to protect (through health insurance), to empower (through OKOBI), and to prepare (through SkillUpImo). They differ in approach, scope, and audience. Still, they converge on a few foundational principles: that development should be human-centred, that dignity should be preserved across social classes, and that opportunity should not be reserved for the privileged few. These are not minor aspirations. They reflect a moral architecture that values inclusion, interdependence, and a shared social future.

Advertisement

Of course, none of these policies exists in a vacuum. Each is situated within a broader institutional, cultural, and economic context. However, what makes them noteworthy from a conceptual standpoint is that they are not simply reactive. They are proactive attempts to reimagine what the government can do, not only in terms of services delivered but also in the relationships it fosters between citizens and the state. They carry the marks of a governance philosophy that sees people not as passive recipients of policy, but as active participants in shaping their own lives.

This approach to governance, rooted in shared responsibility and dignity and oriented toward possibility, is not necessarily loud or spectacular. It doesn’t always lend itself to quick wins or viral headlines. But it creates a more sustainable foundation for trust, engagement, and social cohesion. Policies shaped by such values are more likely to endure because they are not built merely on ambition or administrative expediency but on an ethic of care.

In this sense, we see in these initiatives a move toward a more empathetic form of statecraft that takes the emotional, cultural, and existential dimensions of development seriously. By linking health, livelihood, and learning in a morally coherent way, these programmes offer a vision of governance that is as much about who we want to become as a society as it is about what we want to build.

And that’s what drives Uzodimma’s policies. It’s not about image or politics. It’s about the human core that drives the work. It’s about the way compassion, when rooted in leadership, can shape programmes that don’t just sound good, but feel right. It’s not something you’ll always see on the front pages. But for those who’ve seen it up close, it’s real.

Advertisement

And when public trust is so low, and people are rightfully sceptical of those in power, maybe it’s worth sharing that side, not to praise, but to bear witness.

This is the real story worth telling—not just that new things are happening in Imo State, but that they are happening in ways that reflect a deliberate and value-driven imagination of the good society.

Amaeshi is a professor of sustainable finance at the European University Institute, Florence, Italy, and professor of business and sustainable development at the University of Edinburgh, UK. He currently serves as the chief economic adviser to the Imo State Government.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.