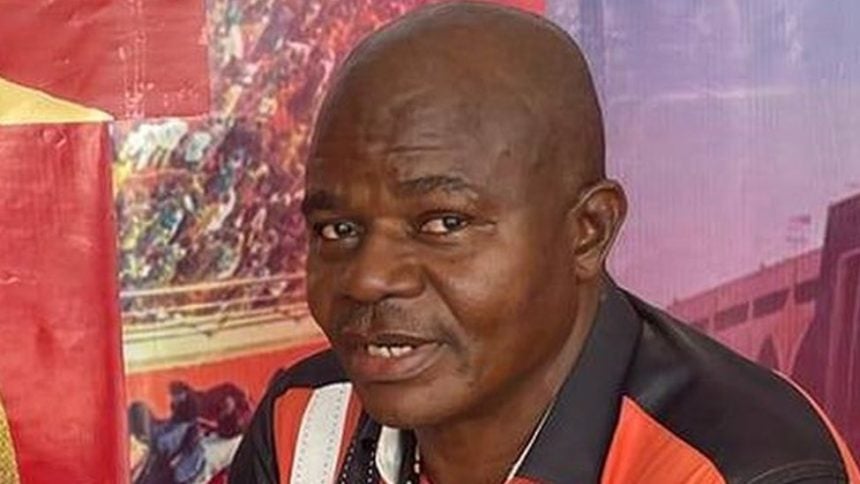

Peter Nwachukwu

BY DAVID BASSEY ANTIA

The recent judicial pronouncement sentencing Peter Nwachukwu, husband of the late gospel singer Osinachi, to death by hanging has reignited the perennial debate surrounding capital punishment in Nigeria. Citizens, scholars, and legal minds have waded into the fray with varying degrees of moral and legal fervor, yet the discourse continues to swing like a pendulum—between vengeance and virtue—without adequate analytical depth or jurisprudential clarity. While abolitionists have spared little effort in introspective concession, the retentionists have shown equal reluctance to critically engage the merits of their counterparts’ propositions.

This pendulum, in my view, swings with too great a momentum to permit repose at the median of reason. At one extreme lies the call for vengeance, where retributive justice is exalted; at the other, a demand for virtue and moral transcendence. Yet I contend that the claim made by abolitionists—that the eradication of the death penalty is the litmus test for a society’s passage from primal instinct to civilization—is a progressive fallacy, a label I assert without equivocation.

Empirically, more lives are lost to homicide than to war. According to the United Nations, approximately 464,000 people were murdered globally in 2017, far exceeding the 89,000 deaths attributed to armed conflict within the same period. The execution of a convicted murderer sends a resounding message: that the sanctity of the innocent life taken is so grievously violated that the ultimate sanction is both warranted and symbolic. No indulgence must be granted to euphemisms that diminish the sacredness of life under the guise of moral posturing.

Advertisement

Punishment, in this context, is not a barbaric relic but a societal response to the catalytic instinct to offend. It serves to slow the instinctual metabolism that spurs the commission of crime. It operates as a neutral but potent force, imposed to assuage the public’s moral indignation and to mark—visibly and unequivocally—the collective revulsion towards heinous conduct. Thus, capital punishment, while partly deterrent, is fundamentally retributive. He who takes life must forfeit his own.

But before I cast my philosophical net around the abolitionist argument and allow it to drown in the sea of insignificance, it is prudent to offer a jurisprudential exposition on the legal architecture of the death penalty.

Capital punishment, by definition, is the legally sanctioned execution of a person as punishment for a crime deemed capital in nature. According to Section 36(12) of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, only offences defined in written law may attract penal consequences. Offences attracting capital punishment include those stipulated under Sections 37 and 319 of the Criminal Code Act (Cap C38, Laws of the Federation of Nigeria, 2004), and Sections 221 and 411 of the Penal Code (Northern States) Federal Provisions Act (Cap P3, Laws of the Federation, 2004). These offences include murder, armed robbery, and treason.

Advertisement

Exemptions exist. Pregnant women, under Section 404 of the Administration of Criminal Justice Act, 2015, and persons under 17 years of age, as reaffirmed in Madupe v. State (1988) 4 NWLR (Pt. 87), are constitutionally and judicially shielded from capital punishment. The Supreme Court in that case held that it is legally impermissible to sentence to death anyone under 17 at the time of the offence.

Further, the courts have consistently upheld the constitutionality of the death penalty. In Adeniji v. State (1998) 14 NWLR 584, the Court of Appeal declared that the death penalty is expressly provided for in Section 33(1) of the 1999 Constitution. The Supreme Court reaffirmed this position in Kalu v. State (1998) 13 NWLR 531 and Okoro v. State (2000) 49 NWLR 356, holding that capital punishment and its method of execution remain lawful and valid, sanctioned by both Sections 33(1) and 34(1)(a) of the Constitution.

Hence, it is imperative to clarify that the death penalty has not been abolished in Nigeria. Its legality stands unassailed, unmoved by the abstract arguments of those who deal in normative wishfulness. Capital punishment remains an integral feature of Nigeria’s criminal justice system.

It is also critical to emphasize the procedural role of the executive in the administration of capital sentences. In Ajulu & Ors v. Attorney General of Lagos State, the Federal High Court restrained the execution of five condemned inmates, noting that execution warrants must be duly signed by the state governor.

Advertisement

For a conviction in a murder trial that carries a death sentence, the prosecution must establish the following elements: (a)That the deceased is dead;(b) and (c)That the death resulted from the act or omission of the accused.

That the act or omission was intentional and calculated with the knowledge that death or grievous harm was a likely outcome. See Okeke v. State (1999) 2 NWLR (Pt. 590) 273.

The standard of proof remains “beyond reasonable doubt” as required by Section 135 of the Evidence Act, 2011. As held in Isah v. State (2018) 8 NWLR (Pt. 1621) 346 and Itodo v. State (2020) 1 NWLR (Pt. 1704) 1, the evidence must leave no room for reasonable doubt—not all doubt, but any doubt that a reasonable person could entertain.

Historically, the African worldview—including Nigerian customary traditions—has recognized the death penalty for murder, notwithstanding the formal abolition of customary criminal offences by Section 36(12) of the 1999 Constitution. The lex talionis principle (“an eye for an eye”) finds its roots not just in tradition but in sacred texts such as Exodus 21. Immanuel Kant himself affirmed the necessity of capital punishment for murder, arguing that punishment must be proportionate to the crime—and death is the only proportionate response to the taking of life.

Advertisement

It is a judicial safeguard, not anachronism, that murder is distinguished from manslaughter in order to ensure that the death penalty is not blindly applied. Cases where intent is lacking are rightly spared from the noose.

To assert, therefore, that capital punishment is archaic is to yield uncritically to the tides of liberal modernity. One might ask: if capital punishment fails to eliminate crime, should we then abolish all punishments, since theft, rape, and fraud persist despite criminal sanctions? Such reasoning collapses under its own weight.

Advertisement

Amnesty International reported 579 executions in 18 countries in 2021, a 20% increase from 2020. As of that year, 56 countries still retain capital punishment; 111 have abolished it entirely. That global diversity reflects not backwardness but sovereignty of moral judgment rooted in unique legal traditions and societal needs.

I submit unequivocally—that Nigeria should retain the death penalty within her criminal jurisprudence. When an innocent life is extinguished, a crime against humanity has been committed. Though the victim cannot demand justice, society can and must. Justice, as Aristotle would say, is giving each their due. And due process, as ratified by constitutional jurisprudence, demands that the ultimate crime warrants the ultimate punishment.

Advertisement

Not all practices of our ancestors are to be discarded. Let us not be too eager to embrace liberal idealism at the expense of introspection. The emotion of vengeance, often caricatured, is in fact foundational to the rule of law. It is what prevents self-help and underpins the legitimacy of state-sanctioned justice. If the state monopolizes coercive power, it must wield it justly—and sometimes, justly means finally.

The abolition of the death penalty would not mark an evolution of justice, but its asphyxiation.

Advertisement

David Bassey Antia, president, Council of Topfaith University Students, can be contacted via [email protected]

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.