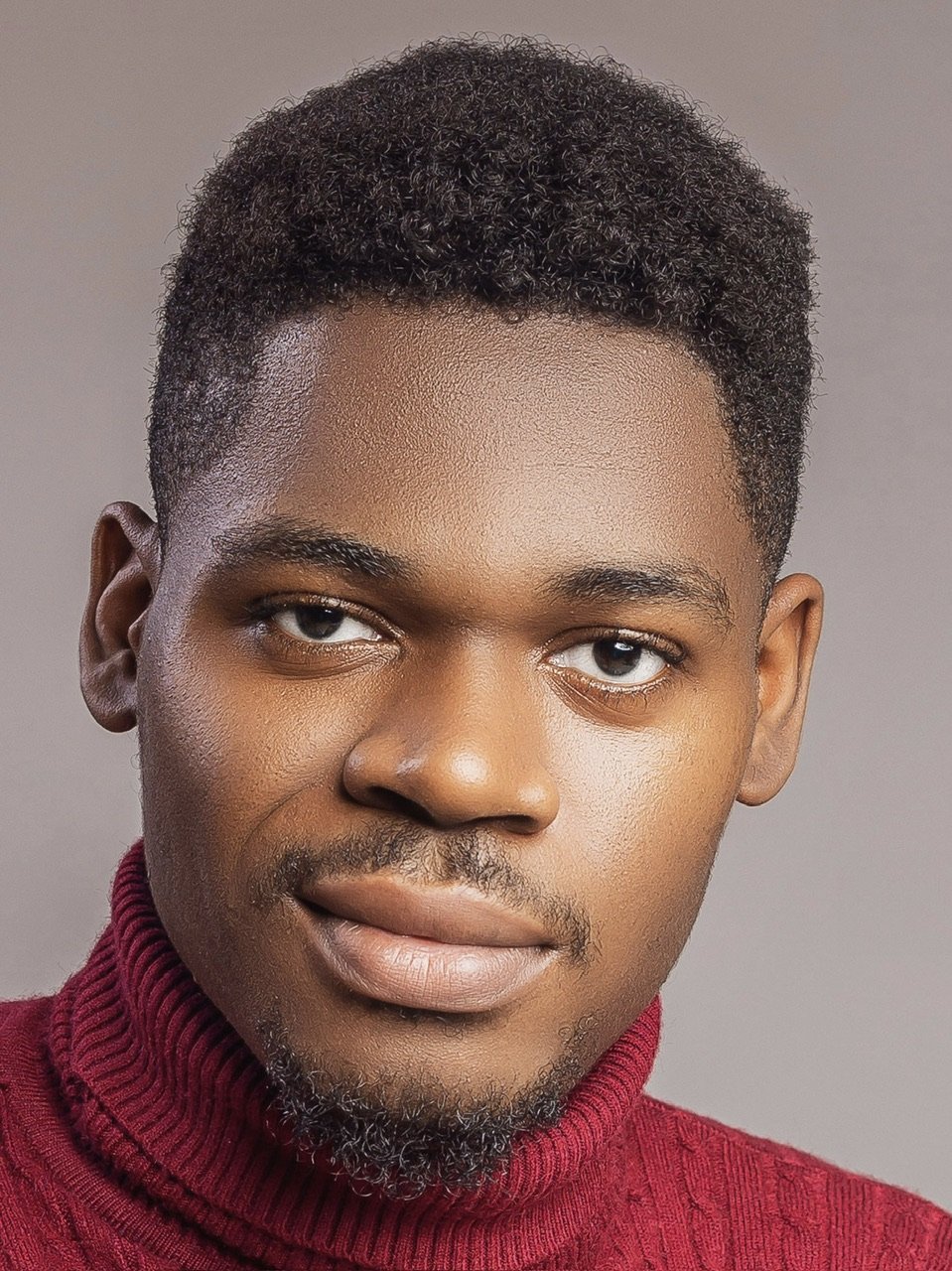

A nomadic student, Jaafar Muhammed, at NPS Wuro Nyako in Kachia LGA of Kaduna State. | Photo By Samuel Adebanjo for TheCable.

Banditry has haunted Nigeria for years, casting a shadow of fear, carnage, and instability, particularly across northern states. The human cost is staggering, the statistics horrifying. Thriving communities are displaced, and livelihoods are severely disrupted.

Parts of Nigeria have had a long history of farmer-herder conflict driven by the tussle for land and water resources. This conflict slowly yielded a network of criminality that would come to be known as “banditry”.

Limited economic opportunities forced marginalised people into joining these bandit groups as a means of survival. Inadequate law enforcement in remote rural communities created a vacuum that bandits exploited.

The spread of small arms escalated the intensity of bandit attacks, with the changing climate and stretching deserts worsening resource scarcity. Cattle rustling and abduction for ransom became lucrative, resulting in a cycle of almost never-ending bloodshed, reprisal attacks, and migration.

Advertisement

Banditry is a composite crime that includes abduction, massacre, rape, cattle rustling, illegal firearms possession, and even unlicensed mining.

Analysts say what served to catalyse banditry in Nigeria over a decade ago may no longer solely be what drives it.

Advertisement

Reports indicate that bandit culture has spread beyond its north-west roots. It is now affecting Taraba and Adamawa in the north-east, where it overlaps with insurgency. It is also affecting Oyo, Ondo, Ogun, and Ekiti in the southwest.

Casualties of banditry became a recurring feature in Nigeria’s news cycle, with a wave of strange killings now being reported in Plateau and Ondo states.

A crime perception survey, published by Nigeria’s statistics office in 2024, estimated that 614,937 people were killed, with 2,235,954 kidnapping incidents recorded between May 2023 and April 2024 alone. A staggering N2.23 trillion was paid as ransom, averaging about N2.7 million per incident.

The CDD gives an admittedly tenuous estimate of at least 100 bandit groups operating in Nigeria’s northwest alone, constituting between 10,000 and 30,000 armed militants. The bandits, it states, have predominantly been Fulani nomads but also include Hausa, Kanuri, Tuareg, and other tribes.

Advertisement

Military action is crucial as an immediate response to bandit activity, but there is a more sustainable solution in addressing the issues that make Nigeria’s nomadic communities vulnerable to indoctrination by bandits.

Among these, the chronic neglect of education for Nigeria’s nomads stands out as a critical, yet often overlooked, factor.

Mindful of undue ethnic profiling, one could argue that the rise of banditry in regions with nomadic people is not random. It is connected to those socio-economic vulnerabilities that have historically persisted.

Advertisement

In rural areas where cattle rearing thrives, livestock rustling is a major crime committed by armed bandits. For pastoralist communities, the theft of their herds can be devastating, pushing them into destitution and potentially into the ranks of bandits either for survival or retaliation.

Social dislocation, the seemingly attractive benefits of banditry, and a pervasive loss of hope entice nomads to join gangs in search of a semblance of socio-economic stability and a way out of poverty.

Advertisement

The high poverty index and youth underemployment in the northwest illustrate this.

This desperation is often exploited by criminal networks that thrive on the illegal trading of rustled livestock and the proliferation of illicit arms.

Advertisement

Education offers a potentially promising solution to this complex crisis.

Advertisement

Inadequate access to quality basic education for Nigeria’s nomadic children paints a vivid picture of inequality and neglect.

Nigeria’s commission for nomadic education says nomadic literacy rate is at 10 to 12 per cent, with an estimated 5.5 million out-of-school nomadic children idling around huts.

This educational deprivation hinders social mobility and economic growth for the nomads.

The nomadic way of life, marked by migration in search of pasture and water, is too disruptive to allow them to attend conventional schools. The centrality of child labour in their trade also compounds this.

Although Nigeria has had an agency tasked with overseeing nomadic education since 1989, its educational initiatives have been plagued by chronic underfunding, inadequate infrastructure, and a severe shortage of qualified teachers willing to work in often insecure remote locations.

Problems with reach and the number of available nomadic schools mean that the average enrollment rate of nomadic children sits at 1.6 million.

This drives a cycle of illiteracy and limits the opportunities available to nomads, making them susceptible to the false promises of banditry.

Nomads have contributed to Nigeria’s local economy through livestock rearing for centuries, but shifting land use patterns, driven by agricultural expansion, deforestation, and the creation of protected areas, have reduced the availability of traditional grazing lands and disrupted age-old migration routes.

Inadequate state support and the weakening of traditional authorities that resolved disputes left nomads feeling confined to the fringes of society.

The nomads in Nigeria, hence, need social intervention in the form of education to re-integrate with society, participate in the methods of modern commerce, and thrive economically.

Policy experts and lawmakers are increasingly recognising the connection between education and security in Nigeria’s nomadic regions.

There is a growing understanding that giving quality education to nomadic youth is indeed a modern tool for conflict prevention and peacebuilding.

Education offers an alternative pathway to employment and a sense of purpose that can reduce the vulnerability of nomads to recruitment by bandits who often prey on the uneducated and unemployed.

Education can foster understanding between nomads and other ethnicities, helping to bridge cultural divides and mitigate communal tensions. By teaching critical thinking, education can promote a rejection of violence as a means to address grievances.

The fact that bandits have targeted schools highlights the threat they perceive from an educated populace, since schooling makes people less susceptible to manipulation and control.

As Nigeria’s senate president Godswill Akpabio once warned, the unschooled children of today risk becoming the bandits of tomorrow.

Nigeria can learn from countries that have successfully tackled challenges related to marginalised nomadic populations who are involved in conflict.

Mongolia scored some success in providing formal education to its nomadic population through state-sponsored residential schools.

Uganda’s “Alternative Basic Education for Karamoja” demonstrates how flexible learning hours, a culturally relevant curriculum co-written by the community, and local teachers can help reach nomadic pastoralists.

Kenya also experimented with mobile schools and distance learning after recognising the need for flexible delivery models to cater to its nomads.

Stories from Afghanistan’s mobile schools and radio-based learning for Kuchi children are there to cite.

Niger’s UNICEF-backed model schools for nomad zones show innovation in reaching remote and mobile communities.

A combination of state support, community involvement, culture-sensitive curricula, and flexible delivery methods is crucial for successful nomadic education programmes in conflict-prone regions.

Education can break the cycle of banditry in Nigeria’s nomadic regions.

By providing relevant skills and knowledge, it potentially opens doors to alternative livelihoods beyond traditional pastoralism, which is increasingly vulnerable to climate change and resource conflict.

Literacy and numeracy skills, coupled with vocational training, can equip nomadic youth with the means to participate in the modern economy.

Since education drives belonging, mingling nomadic children with their peers from other communities can dismantle the resentment that fuels conflict.

Providing quality education to nomadic communities in Nigeria is fraught with logistical, cultural, and political challenges.

The mobile nature of nomads necessitates flexible school models, such as mobile schools and distance learning schemes, which require investment in infrastructure and technology in often remote and inaccessible areas.

Recruiting and retaining teachers in these environments is a challenge that requires improved incentives and enhanced security.

As traditional nomadic livelihoods are ingrained, curricula that incorporate local languages, traditions, and relevant skills will ensure the value of education is recognised in these communities.

It requires strong political will, sustained funding, coordination at all levels of government, and partnership with non-profits.

Nigeria’s war against banditry demands a comprehensive strategy that tackles underlying social, economic, and educational vulnerabilities.

Educating Nigeria’s nomads is not a matter of social justice. It is an imperative for national security.

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.