The supreme court has weighed in on Nigeria’s emergency rule framework following legal challenges triggered by the declaration of a state of emergency in Rivers state — a development that saw the suspension of elected officials and the appointment of a sole administrator.

On March 18, President Bola Tinubu declared a state of emergency in the south-south state, citing a prolonged political crisis and the vandalism of oil installations. He subsequently suspended Siminalayi Fubara, governor of Rivers state; Ngozi Odu, his deputy; and all members of the Rivers state house of assembly for six months.

Tinubu also appointed Ibok-Ete Ibas, a retired vice-admiral, as the sole administrator of the state. The senate and the house of representatives later approved the president’s request for emergency rule.

Shortly after the proclamation, 12 states under the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), led by their attorneys-general, approached the apex court to challenge the president’s powers to suspend democratically elected officials under the guise of a state of emergency.

Advertisement

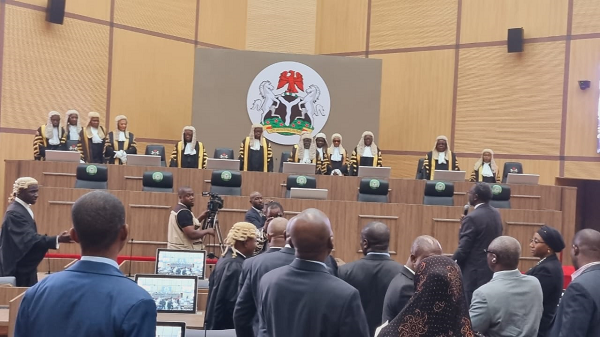

Although the emergency period has elapsed and all suspended officials returned to office in September, the supreme court delivered its judgement on Monday.

ISSUE OF JURISDICTION

The supreme court held that it lacked jurisdiction to entertain the suit, ruling that the plaintiffs failed to establish a dispute capable of invoking its original jurisdiction under section 232(1) of the 1999 constitution.

The court explained that its original jurisdiction is strictly limited to disputes between the federation and a state, or between states, where the existence or extent of a legal right is in issue. In this case, the justices found that none of the plaintiff states was Rivers state, which was the state directly affected by the emergency proclamation being challenged.

Advertisement

“… none of the plaintiffs represents Rivers state, and neither did they establish any authority to litigate on its behalf,” the court held.

It further noted that none of the plaintiffs demonstrated that a state of emergency had been declared in their states. The justices also rejected reliance on an alleged statement made by the attorney-general of the federation during a media briefing, which the plaintiffs construed as a threat to their respective states.

“Such a statement, standing alone, cannot constitute an actionable conduct of the Federation itself for the purpose of invoking Section 232(1). Complaints directed against individual officials or functionaries of the Federal Government, even when acting in their official capacities, do not amount to disputes between the Federation and a State within the contemplation of the Constitution,” the court said.

In the absence of a reasonable cause of action disclosing a live dispute, the apex court concluded that the suit was incompetent and accordingly struck it out.

Advertisement

CAN A PRESIDENT SUSPEND A DEMOCRATICALLY ELECTED OFFICIAL?

Despite striking out the case for lack of jurisdiction, the supreme court said it considered it necessary to clarify the constitutional framework governing emergency rule in Nigeria.

At the centre of the debate is section 305 of the 1999 constitution, which empowers the president to proclaim a state of emergency under defined circumstances.

In a majority judgement, the court held that section 305 is “clear in its grant of power to proclaim a state of emergency but silent on the precise content of the ‘extraordinary measures’ that may follow”.

“This silence is intentional,” the court said.

Advertisement

The justices noted that while constitutions in countries such as India and Pakistan expressly allow the president to assume executive and legislative powers where constitutional governance has failed, Nigeria’s constitution “does not expressly confer power on the President to assume or temporarily displace the executive or legislative institutions of a State”.

“This omission is deliberate and reflects Nigeria’s constitutional commitment to federalism and the autonomy of state governments,” the apex court held.

Advertisement

The court acknowledged that emergencies are inherently unpredictable and vary in severity, explaining that Nigeria’s past emergency declarations show there is no fixed template for response.

“Emergencies are inherently situational, varying in scope, intensity, and threat,” the court ruled.

Advertisement

It said the constitution, therefore, entrusts the president with discretion to determine the measures required to restore peace and security, subject to constitutional limits, proportionality, legislative oversight, and judicial review.

“Historical practice in Nigeria illustrates this flexibility. During the 2004 and 2006 emergencies in Plateau and Ekiti States, respectively, the executive and legislative institutions of the states were suspended. By contrast, during the 2013 emergency in Borno, Adamawa, and Yobe States, state institutions continued to function,” the court said.

Advertisement

“These contrasting responses underscore that emergency powers are not governed by a rigid formula. The constitutionally permissible response depends on the magnitude of the threat, the functionality of state institutions, and the necessity of intervention to restore constitutional order.”

LIMITS TO PRESIDENTIAL DISCRETION

Nevertheless, the apex court stressed that presidential discretion under section 305 “is not unfettered”.

“Emergency measures must be temporary, corrective, and proportionate. They must be directed towards restoring constitutional governance, not extinguishing it. Any permanent displacement or abrogation of democratically elected institutions would constitute a constitutional aberration,” the court held.

It added that “outside a validly declared state of emergency, the President possesses no power whatsoever to interfere with state executive or legislative institutions”.

The court further held that the constitution places emergency rule under strict legislative control, stressing that a proclamation of a state of emergency automatically lapses unless approved by a two-thirds majority of all members of each chamber of the national assembly within the stipulated time.

According to the justices, this requirement ensures that emergency powers reflect a broad national consensus rather than unilateral executive action.

The apex court added that although the constitution does not prescribe a specific voting method, the national assembly’s standing orders, which have constitutional force, provide clear procedures for verifying the required supermajority.

“In the Senate, the relevant procedure is governed by Orders 133–136 of the Senate Standing Orders, 2023 (as amended), and voting is conducted in accordance with Chapter X thereof, particularly Orders 70–72 and 71, which recognise voice vote, division by signing a register, or electronic voting,” the court said.

“A formal numerical division is required where the opinion of the presiding officer is challenged. What remains constitutionally imperative is that the process adopted renders the attainment of the two-thirds majority clearly ascertainable.”

The court concluded that an emergency proclamation — and any suspension of elected officials flowing from it — can only be constitutionally valid when duly issued, properly approved, implemented through temporary and proportionate measures aimed at restoring constitutional order, and subject to judicial review to prevent abuse.

The majority judgement was delivered by six justices of the seven-member panel.