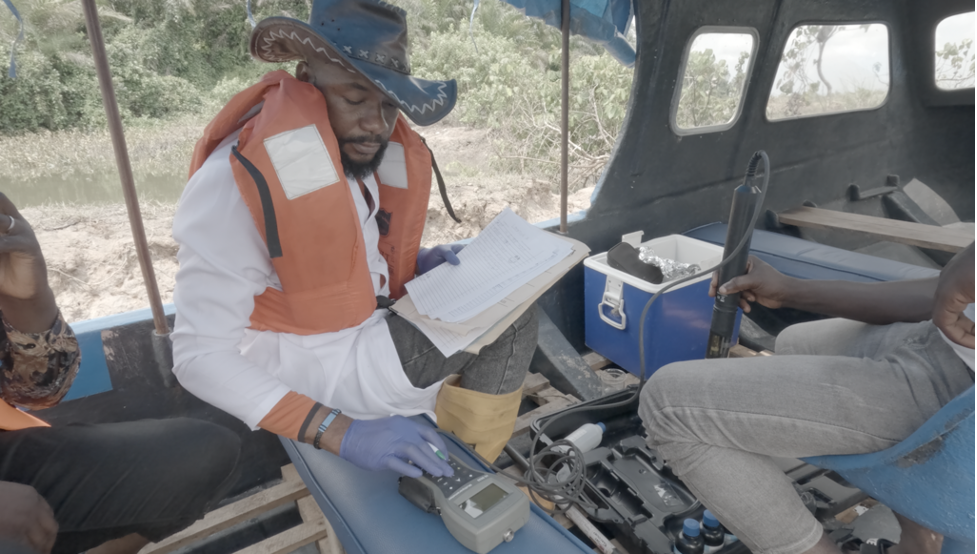

Fisherman Nombare Tabu sits in his canoe at Nweemy creek, Bodo. Pulitzer/AnuOluwapo Adelakun

Nombare Tabu sets his trap in Bodo Creek every other day, just as his father taught him decades ago. But when he returns the next morning, his catch tells a different story than the one his grandfather might have recognised. The fish emerge from the water coated in crude oil, their scales glistening with black slick that floats perpetually on the creek’s surface.

At 70, Tabu can no longer venture into the Atlantic Ocean for the big catches that once sustained his family. So he does what necessity demands: he rinses the oil-covered fish with water from the same contaminated creek and cooks them for his daily meals.

“Every living thing was affected,” says Chief Nadabel, leader of the nearby Nweemuu fishing village, his voice heavy with the weight of what his community has lost and what it continues to endure.

WHEN FISHING VILLAGES BECOME GHOST TOWNS

The two-hour journey from Port Harcourt to Bodo reveals a landscape still bearing the scars of catastrophic oil spills from 2008 and 2009. At the bustling Bodo jetty, rickety boats ferry passengers between creek communities, their operators navigating waters where military speedboats patrol and HYPREP clean-up crews work in orange vests among the mangroves.

Advertisement

But the 15-minute boat ride to Nweemuu fishing village tells a starker story. Empty fishing boats sit idle on the beach. Nets hang abandoned on dying trees. Once-thriving structures now stand incomplete and overgrown with weeds, monuments to a community that has largely fled.

“Before this pollution, the total population here was 1,300 people—even more,” Chief Nadabel explains. “But now, we’re not more than 130-something people living in the community.”

The numbers capture what the landscape already reveals: when oil contamination destroys fishing grounds, entire communities disappear. Families who built their lives around these waterways for generations simply packed up and left, seeking survival in urban areas where they could start over.

Advertisement

THE ECONOMICS OF ENVIRONMENTAL DEGRADATION

The Niger Delta was once the world’s greatest wetland, its freshwater marshes supporting immense biological diversity. More than 70 percent of the local population depends on fishing, farming, and forestry for survival, creating an intricate economic web that extends far beyond individual families.

These waters sustained fish processing facilities and bustling markets, traditional boat carving and net weaving. The dense mangrove forests provided additional income streams palm wine, local gin, and palm oil for industrial use. When oil spills occur, they don’t just contaminate water bodies; they collapse entire economic ecosystems.

Abel Naana understands this collapse intimately. The 50-year-old fisherman from neighbouring Mogho community was born into fishing, trained from childhood by his father, who learned from his grandfather. “Back when things were fine, the fishing lifestyle was so vibrant,” he recalls. “We fished in the morning and at night.”

The business was so profitable that fishermen built huts right at the riverbank for easy access, sorting, and rest. Naana married, raised children, and built a house entirely from fishing income. Since the 2008-2009 oil spills transformed Bodo River from a thriving ecosystem into what he calls “a floating morgue of aquatic life,” that prosperity has vanished.

Advertisement

“When I look at my house now, it reminds me of the life I once had which was stolen by the oil spills,” Naana says, standing before the house built through fishing. “The corruption surrounding the clean-up project makes me worry that fish will never return to our river.”

THE SCIENCE OF POISONED WATERS

Dr. Lebari Sibe of the University of Port Harcourt arrived at Bodo Creek with a team of environmental chemists to document what residents like Tabu and Naana experience daily. Using standard methods for testing surface water, sediments, and aquatic life, they analysed samples for seven heavy metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and total petroleum hydrocarbons.

Their findings reveal contamination so severe that it threatens both aquatic ecosystems and human health:

Heavy Metal Bioaccumulation: Tilapia fish showed alarmingly high levels of nickel (0.701 mg/L) and copper (0.371 mg/L). Periwinkles contained elevated chromium (0.070 mg/L) and iron (0.863 mg/L). Lead levels in both species exceeded EPA safety thresholds. Tilapia contained 0.051 mg/L while periwinkle measured 0.027 mg/L, both surpassing the safe limit of 0.012 mg/L.

Advertisement

Water Quality Crisis: Total dissolved solids reached 14,730 mg/L—nearly three times the WHO regulatory limit of 5,000 mg/L. Electrical conductivity, an indicator of pollution levels, measured 23,300 µS/cm in surface water and 24,860 µS/cm in sediment, far exceeding the WHO guideline of 500 µS/cm.

Carcinogenic Compounds: High concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, including benzo(a)pyrene and benzo(k)fluoranthene both known carcinogens linked to oil pollution were found in sediments.

Advertisement

CHILDREN WHO WILL PAY THE PRICE

“These chemicals accumulate in our system and can potentially reach levels that trigger severe health complications,” Dr. Sibe explains. The bioaccumulation process means toxic chemicals transfer through the food chain, with fish consuming contaminated marine life and gradually storing harmful chemicals that ultimately reach human consumers.

While adults face relatively low cancer risks from contaminated seafood, children tell a different story. Nickel and chromium exposure in children exceeds safety thresholds, potentially causing toxic effects with prolonged consumption. Children consuming tilapia from Bodo Creek face significantly higher cumulative toxicity risks than adults.

Advertisement

The health implications lurking in the future include various forms of cancer, genetic mutations, neurological disorders, cardiovascular complications, and organ damage, particularly affecting kidneys and lungs. These risks fall disproportionately on the youngest residents those who had no choice in the environmental destruction they’ve inherited.

Advertisement

HYPREP’S SLOW PROGRESS AMID ONGOING CONTAMINATION

The Hydrocarbon Pollution Remediation Project, established in 2011 to address Ogoniland’s extensive environmental damage, has become a symbol of bureaucratic struggle rather than environmental restoration. In a December 2024 report, Professor Nenibarini Zabbey, the project coordinator, highlighted some progress: 75% completion of mangrove restoration covering 560 hectares, with over 1 million mangroves planted, and 20% completion of shoreline remediation.

Yet significant challenges remain. The $1 billion clean-up project launched in 2016 has been hampered by delays and implementation issues. As recently as July 2024, the Trans Niger Pipeline in Sugi, a settlement within Bodo, suffered another spill, dumping oil onto farmlands in the same area that experienced similar incidents in August 2022.

The gap between reported progress and ground-level reality remains stark. While HYPREP plants mangroves and conducts remediation activities, families like Tabu’s continue eating oil-contaminated fish because they have no other choice.

VANISHING CUPPLY CHAIN

The contamination crisis extends beyond individual families to entire economic networks. Fish sellers who once travelled weekly between communities now find little to purchase. Food vendors who built businesses around fresh seafood face dwindling supplies and questionable quality.

The traditional fishing huts that Abel Naana said were built at riverbanks for easy access during busy fishing seasons now stand empty. The vibrant morning and evening fishing routines that sustained communities have been replaced by the desperate efforts of elderly fishermen like Tabu, who risk their health because they have few alternatives.

Markets that once buzzed with fresh catches and competitive pricing now operate on scarcity and contamination. The interconnected businesses from net repair to boat maintenance, from fish processing to transportation have withered along with the fish populations.

30-YEAR RECOVERY TIMELINE

UNEP estimates that complete recovery from oil pollution in the region could take another 30 years and that’s assuming no new oil spills occur. For children growing up in communities like Nweemuu and Mogho, this timeline represents entire lives lived in contaminated environments.

The projection paints a sobering picture: today’s young people may become what Dr. Sibe calls “the sickly generation of the future,” bearing the accumulated health impacts of decades of environmental destruction and slow remediation efforts.

The scientific findings confirm what residents have experienced for over a decade: the pollution persists, the health risks compound, and the clean-up efforts, while ongoing, remain insufficient to match the scale of contamination.

THE PRICE OF OIL, PAID IN LIVES

Nombare Tabu continues setting his traps in Bodo Creek because the alternative is starvation. Abel Naana looks at the house fishing built and wonders if his children will ever know the prosperous waters his grandfather described. Chief Nadabel leads a community of 130 where 1,300 once thrived.

Their stories illuminate a fundamental environmental justice question: What constitutes acceptable risk when entire communities have no choice but to consume contaminated food and water?

The contaminated seafood in Bodo Creek represents more than a public health crisis. It embodies the long-term consequences of environmental destruction on communities with limited resources and fewer alternatives. While clean-up efforts continue and scientific studies document the damage, families continue eating oil-covered fish because survival demands it.

Until remediation efforts match the scale of contamination, and until communities have access to safe food and water alternatives, the children of Bodo Creek will continue inheriting a poisoned legacy they played no role in creating.

The fish may be contaminated, but for families like Tabu’s, finding fish, even poisoned ones, remains a matter of daily survival.

Adelakun is a Nigerian journalist and filmmaker whose documentary “Finding Fish” investigates seafood contamination in Nigeria’s oil-affected communities. This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

.