On Monday, global attention will turn to Brazil as it hosts the 30th session of the United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP30), where world leaders are expected to chart a decisive course toward limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C.

This year’s conference takes place in Belém, the capital of Brazil’s Pará state, deep in the heart of the Amazon — a region that holds over 60 percent of the world’s tropical rainforests and serves as one of the planet’s most vital carbon sinks. The Amazon’s future is seen as central to the global fight against climate change, making Belém a symbolic venue for critical climate negotiations.

A new study found that the Amazon rainforest — the world’s largest tropical forest, spanning over 6 million square kilometers and home to about 10 percent of Earth’s plant and animal species — may be approaching a dangerous tipping point that could transform the ecosystem into a parched savanna within the next century.

Advertisement

Backed by the Latin American and Caribbean region, and under the leadership of COP30 President André do Lago, the two-week summit from November 10 to 21 is dubbed the ‘Implementation COP’. It is expected to test countries’ seriousness in turning climate pledges into concrete action.

Although Brazil is an oil-producing nation, hosting COP30 in Belém carries symbolic weight as it shifts the spotlight toward forests and nature-based solutions.

This year’s conference also unfolds against the backdrop of intensifying climate disasters, widening finance gaps, persistent climate denial, and mounting calls for stronger accountability from major emitters. The location is particularly significant, coming after three consecutive COPs in fossil fuel–rich countries, and underscores the urgent need to balance energy interests with forest preservation and global climate action.

Advertisement

In this piece, TheCable attempts to summarise some big issues to watch out for as COP30 begins.

- THE BAKU-TO-BELEM FINANCE ROADMAP

COPs have traditionally centred on how to mobilise climate finance to keep global temperature rise within safe limits. The first global finance goal — a commitment to mobilise $100 billion annually by 2020 — was first made in 2009 at COP15 in Copenhagen and later formalised under the Paris Agreement at COP21 in 2015.

After the expiration and two-year delay of that initial pledge, developed countries at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, agreed to a new contention commitment of $300 billion annually by 2030 and set a global climate finance goal of $1.3 trillion by 2035.

However, what remained unresolved at COP29, which stretched into overtime as negotiators struggled to find common ground, was how this ambitious $1.3 trillion target would be sourced and financed.

Advertisement

COP30 is expected to be where the world determines the mechanisms for raising, allocating, and tracking this funding. For countries in the Global South, particularly small island nations and African countries, the outcome could define whether climate adaptation and clean energy projects finally move from pledges to tangible progress.

- FOREST FUNDING AND NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS

Brazil is spearheading a new forest finance mechanism known as the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF) — an initiative designed to reward countries that conserve their rainforests. With the Amazon as its symbolic backdrop, the TFFF is expected to be unveiled at COP30, where it is likely to emerge as one of the summit’s most prominent and divisive themes.

The facility aims to mobilise $125 billion, combining $25 billion from sovereign and philanthropic sources with $100 billion from private investors. The funds will be reinvested in a diversified portfolio, with annual returns channelled as performance-based payments to countries for every hectare of forest they preserve. Notably, 20 percent of the total fund will go directly to Indigenous peoples and local communities — a provision that underscores the growing recognition of their role in forest protection.

However, some climate campaigners have warned parties to be cautious of the TFFF as it could be another form of debt burden to developing countries, and that it sets complex conditions that Global South countries may not be able to meet.

Advertisement

“African countries must be cautious of the Tropical Forest Forever Facility introduced by Brazil. This fund depends on loans and bonds, meaning that developing countries could end up paying interest through debt finance to carry out conservation. The mechanism sets complex conditions that some of the countries with these forests may not meet. This is neither new nor fair, but another distraction and market-based mechanism that benefits investors more than the countries they claim to support,” said Amos Wemanya, global project co-lead, Fair Share for People and the Planet at Greenpeace, at the launch of Africa’s common position policy brief.

Beyond the TFFF, negotiators are expected to push for scaling up nature-based solutions such as mangrove restoration, reforestation, and sustainable land use.

Advertisement

- THE GLOBAL GOAL ON ADAPTATION (GGA)

First introduced at COP21 in 2015 under the Paris Agreement, the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) aims to enhance the adaptive capacity of vulnerable communities, strengthen their resilience, and reduce their vulnerability to climate impacts.

Advertisement

Unlike mitigation, which has a clear global target of limiting temperature rise to below 1.5°C, adaptation was left without defined indicators for measuring progress.

In its recently released 2025 Adaptation Gap Report, the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) noted that the estimated cost of adaptation in developing countries is now 12 to 14 times greater than current international public finance flows. It added that these countries would require between $310 billion and $365 billion annually by 2035 to cope with worsening climate impacts.

Advertisement

The current flow of adaptation finance to the Global South stands at only about $15 billion a year, far below the region’s estimated annual need of over $70 billion to cope with worsening climate impacts.

After years of slow progress, countries are expected to agree on indicators to measure adaptation progress under the GGA. These indicators will help track how nations are preparing for floods, droughts, and heatwaves — and ensure that adaptation receives the same level of attention as mitigation.

The GGA target is expected to face resistance from developed countries, many of which may be reluctant to make new financial commitments.

- NATIONALLY DETERMINED CONTRIBUTIONS (NDCs)

In 2015, when 195 countries signed the Paris Agreement, committing to limit global temperature rise to well below 2°C and pursue efforts to stay within 1.5°C, they also agreed to submit updated climate targets, known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), every five years to increase ambition.

The first NDCs were submitted in 2015, followed by a second round in 2020. Now, countries are expected to present a new set of enhanced NDCs by the end of 2025, ahead of COP30 in Brazil.

While some major emitters, including China, the United Kingdom, and Germany, have already submitted their updates, others are expected to unveil more ambitious pledges at COP30.

Nigeria, along with several other developing countries, has also submitted its updated NDC ahead of the September 11 UNFCCC deadline, committing to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 32 percent by 2035 compared to a business-as-usual scenario and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060.

At COP30, countries will focus on how they can translate these pledges into actionable policies and measurable results, ensuring that global temperature rise stays aligned with the Paris Agreement’s goals.

- JUST ENERGY TRANSITION

As countries move to phase out fossil fuels, local communities that depend on oil, coal, and gas revenues risk losing their jobs and livelihoods. To address this, the Just Transition Work Programme (JTWP) was created to ensure that no one is left behind in the global energy shift — and that the transition is fair, inclusive, and equitable.

At COP30, negotiators will revisit key questions around the scope of the just transition. Should it focus solely on energy systems such as coal, oil, and gas, or extend to broader sectors like agriculture, transport, and manufacturing? They will also debate whether to establish a dedicated finance window to support vulnerable countries and how such funding can be made accessible to developing economies. Parties will seek to guarantee that fairness remains central to the global energy transition, with local communities and workers placed at the heart of the process.

- LOSS AND DAMAGE

Loss and damage refer to the harm caused by climate change that cannot be adapted to. At COP27 in Egypt, countries agreed for the first time to establish a Loss and Damage Fund to help developing nations recover from climate-related impacts. However, it was not until COP28 in Dubai (2023) that the fund was operationalised, with about $700 million in initial pledges.

Since then, questions have lingered over who can access the fund, what qualifies as loss and damage, and how accessible the funds truly are to developing countries. At COP30, negotiators are expected to focus on how to make the Loss and Damage Fund a sustainable and predictable source of finance — shifting from one-off donations to long-term commitments. Discussions will also explore new funding mechanisms, such as taxes on fossil fuels, shipping, and aviation, and push for mandatory contributions from developed countries rather than voluntary pledges.

7) INDIGENOUS VOICES

One unique aspect of COP30 is that it will take place in Belém, Brazil — the gateway to the Amazon — a country home to about 1.7 million Indigenous people who serve as vital custodians of nature and biodiversity. Their voices are expected to resonate strongly at the conference as negotiators seek ways to ensure their meaningful inclusion in climate decision-making, protect their land rights, and prevent climate action from leading to further displacement.

In Nigeria, the oil-rich Niger Delta region, where communities have long suffered the impacts of oil exploration, has continuously demanded climate reparations, arguing that decades of environmental degradation have threatened their livelihoods and existence.

COP30 offers a platform for Indigenous Peoples globally to explore how traditional knowledge can complement scientific approaches in climate adaptation, while also pushing for fair and equitable benefit-sharing mechanisms.

NIGERIA’S COP30 AGENDA

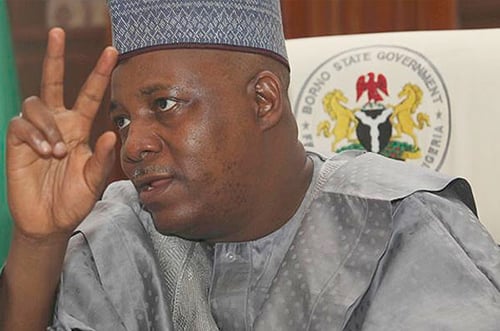

Vice-President Kashim Shettima will represent President Bola Tinubu at COP30, where he will deliver Nigeria’s climate action address and participate in key discussions on climate finance, forest conservation, and the implementation of the Paris Agreement, alongside other world leaders.

He will also participate in the launch of the TFFF and join a roundtable on climate and nature chaired by Brazilian President Luiz Lula da Silva,

In a statement on October 30, Stanley Nkwocha, senior special assistant to the president on media, said Tinubu has set the country’s COP30 agenda, which will be on finding ways to harness financing opportunities for climate-resilient projects and related interventions for the country.

“The Nigerian leader also set the agenda for Nigeria ahead of the forthcoming 30th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 30) scheduled for Belem, Brazil, saying the focus is to harness all of the opportunities for financing climate resilient projects and related interventions, particularly from the global carbon market,” the statement reads.

With the worsening impacts of climate change, thousands of Nigerians continue to bear the brunt of devastating floods across the country. Recent data shows that in 2025, 238 people were killed, over 135,764 displaced, and at least 409,714 individuals across 27 states were affected by flooding.

This year’s COP30, coming a decade after the Paris Agreement, is expected to strengthen global efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C through more ambitious national climate plans and by scaling up climate finance to $1.3 trillion annually for developing countries by 2035. Nigeria is looking to tap into these opportunities, with the engagement in Brazil, projected to unlock between $2.5 billion and $3 billion annually in carbon finance over the next decade to help the country meet its climate goals.