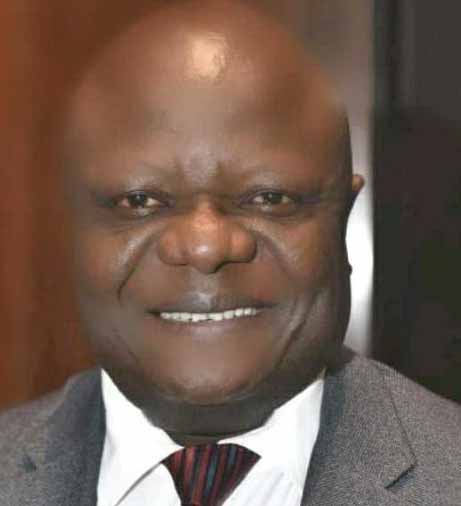

The book, Demonstration of Craze: Struggles and Transition to Democracy in Nigeria” by Abdul Oroh, is a 614-page effort segmented into 30 chapters, with an estimated word count of three hundred thousand (300,000). It is above average in volume and spans multiple nonfiction genres, including autobiography, history, politics, philosophy, sociology, and, in some places, religion, with a few auto-transcendental reflections, such as “voodooism.” From his account, it took him about four years to accomplish, crossing countries to find serenity, talking and meeting with editors for second and third opinions, and more, as well as combing archives for supporting materials. It has become a compendium, likely his most significant volume on Earth. It is not the type that can be done repeatedly. Nevertheless, it is worth it, after all.

Hon. Oroh began in the early chapters by transporting readers to his initial years, his roots and routes, presenting his ancestry in the manner in which you are likely to ask little or no question about Ubiaro, his place of birth, his parentage, family and the overarching picture of the former Bendel state, now Edo and Delta states. He moved on to the neighbouring chapter to demonstrate his promise as a young person, his potential for agitation and the signposts of restlessness.

Courage, conviction, tenacity, and adventure were also in evidence, and at the age of 17, as on Page 16, he thought he was old enough to engage in adult fantasies and indulgences. Hon. Oroh is also lavish in his penetrating analysis of the evolution of Nigerian politics, weaving this with economic and sociological antecedents, as well as the nation’s experiences with friction, conflict, and war. In what he argued reflects the nation’s multi-ethnicity, the struggle for consensus, and the continuing challenges of growth and development, he is imbued with hope if efforts are made to fit the pieces in the right places in the jigsaw.

Moving into the trenches from the newsroom, the author exemplified the quintessential writer and investigative journalist in him, summarising his outstanding travels in this field as a professional. His exploits at The African Guardian were prominent, especially in his newsbreaks, phenomenal interviews, and leadership in news analysis. The change agency within him as a journalist made his detour into the trenches seamless. He was not alone in the dugouts, as in journalism. He had good companies, excellent mentors and beacons on whose trainings he also became. In the trenches, too, he powered on with a libertarian spirit, trusting in human rights and the dignity of the citizen and committing to struggling against violations.

Advertisement

Operating alongside others on the pedestal of the foremost Civil Liberties Organisation (CLO), the writer detailed their fights, revealing the salutary paths of legends like Olisa Agbakoba (SAN), Ayo Obe, Chima Ubani, Chidi Odin Kalu, and a host of other important figures. Hon. Oroh was not done as the book progresses. He is praiseful of freedom, emancipation and the rights of citizens, showcasing in a telling and compelling narrative how the military impostors violated these.

Many were the stories of monitoring their activities, arrests, detentions without trial, escapes, and assassinations, including those of Dele Giwa of the defunct News Watch magazine. His paths, those of CLO and its leadership, as well as those of journalists and advocacy newspapers, including the efforts of other civil society organisations (CSOs), were effortlessly recounted, considering his first-person participant-observatory and sometimes ethnographic depiction of what transpired in those days.

Expectedly, he was not silent on the June 12, 1993, presidential election, a pivotal event that triggered protests and challenged those who sought to maintain the status quo. He thought the military took a Machiavellian advantage of the system, deploying brute force to infringe on citizens’ rights. He fought. They fought. They were arrested. Some died in the process. Others escaped. Some others were jailed. Some lived through it, ironically profiting from an emergent prominence.

Advertisement

A few others remained undaunted and are still as principled as they once were. The narratives are as clear as crystal, ceasing the reader’s imagination to no end and erasing further curiosity about what happened then. The authors’ prison experiences were predictably detailed from one centre to another, from one supervising agency to another, and then to a narrative of the state of detention facilities.

Terrible. Unimaginable. Dehumanising. Reductionist and unfair. He woke up every day wondering if he would ever come out alive. What would become of his wife, Oseme, who was still all over him in detention and their newborns? Eventually, the man managed to come out as a free man. Halleluiah! Hon. Oroh was aware of the local and global dimensions of their struggles for freedom, as well as the support and clamour for their liberty. The consciousness was therapeutic, leading to a consequential detailing of the internal and external calls. The binary may not have resulted in his immediate freedom, but it added to his argument that they should emerge alive.

While the Fela Anikulapo-Kuti rebel philosophies are an obvious subtext in the title of the book, the ideas of the fabulous singer kept resurfacing in the body of the work, particularly in the build-up to democratisation under Gen. Abdulsalami Abubakar (rtd)’s transitional administration. To the author, it was an “Army Arrangement”, even though saluted as a breath of fresh air.

He revealed his knowledge of former President Olusegun Obasanjo and aspects of his administration. From the stability, the promise of sustainability, and the third-term challenge, the writer presented the leader as a man of many parts, with the capacity to be either gung-ho or peaceful. He had begun the book from home, went on an intellectual excursion elsewhere, and started returning home to his state of origin, dwelling on processes and personalities in the closing chapters.

Advertisement

Here, the rise and rise of Comrade Adams Aliyu Oshiomhole were palpable, including an exploration of his administration, his feats and memorable styles, and the author’s role as a commissioner. Hon. Oroh did not just document his understanding of that administration but dwelled on the condition and potential of the state. Consequently, look no further if you want a patriotic citizen of a state. Envisioned in all these is his experience as a member of the House of Representatives, where he participated and witnessed politics, politricks, reward, compensation, loyalty, betrayals, manoeuvres, and horse-trading – away from the newsroom and activism.

No doubt his “Magnum Opus”, but like all such works, it has not come without a few limitations. First, before he became a representative in the National Assembly, all the cars Hon. Oroh rode had been tokunbo. His first official car as a representative was a brand-new Peugeot 406. I was waiting to see this in the book, but I did not. Second, Hon. Oroh’s middle region (or stomach) protrudes easily, just like mine. He was not specific about how the exercise he did in prison caused the protrusion to recede inward, allowing him to pass for a model immediately after his release.

Aside from these two jocular points and some permissible writing idiosyncrasies, the book is an excellent product of a hardworking, dutiful and conscientious citizen whose life has been painstakingly dedicated to the common good. Whichever side you belong to, Hon. Oroh passes as an enigmatic nation builder, a courageous advocate for justice and fairness, a journalist, lawyer, activist, and politician whose legacy will not be forgotten in a hurry.

This book is undoubtedly suitable for both academic and general reading in the fields of activism, law, history, political science, and sociology, as well as for a secular understanding of a particular era in Nigeria. It is therefore highly recommended for one and all. Congratulations, Hon. Oroh.

Advertisement

Adeniyi is a professor of communication and registrar at Baze University, Abuja.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.