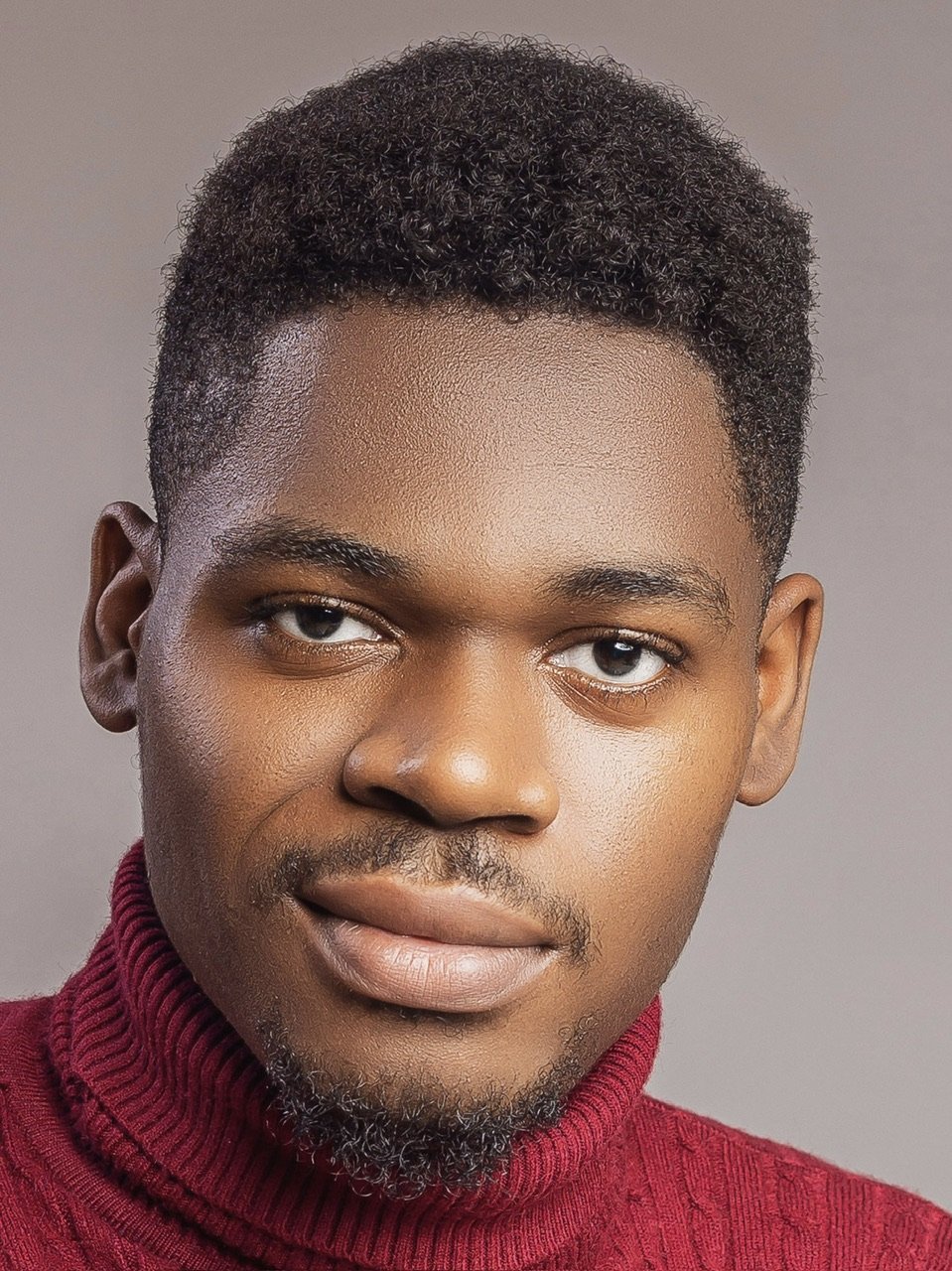

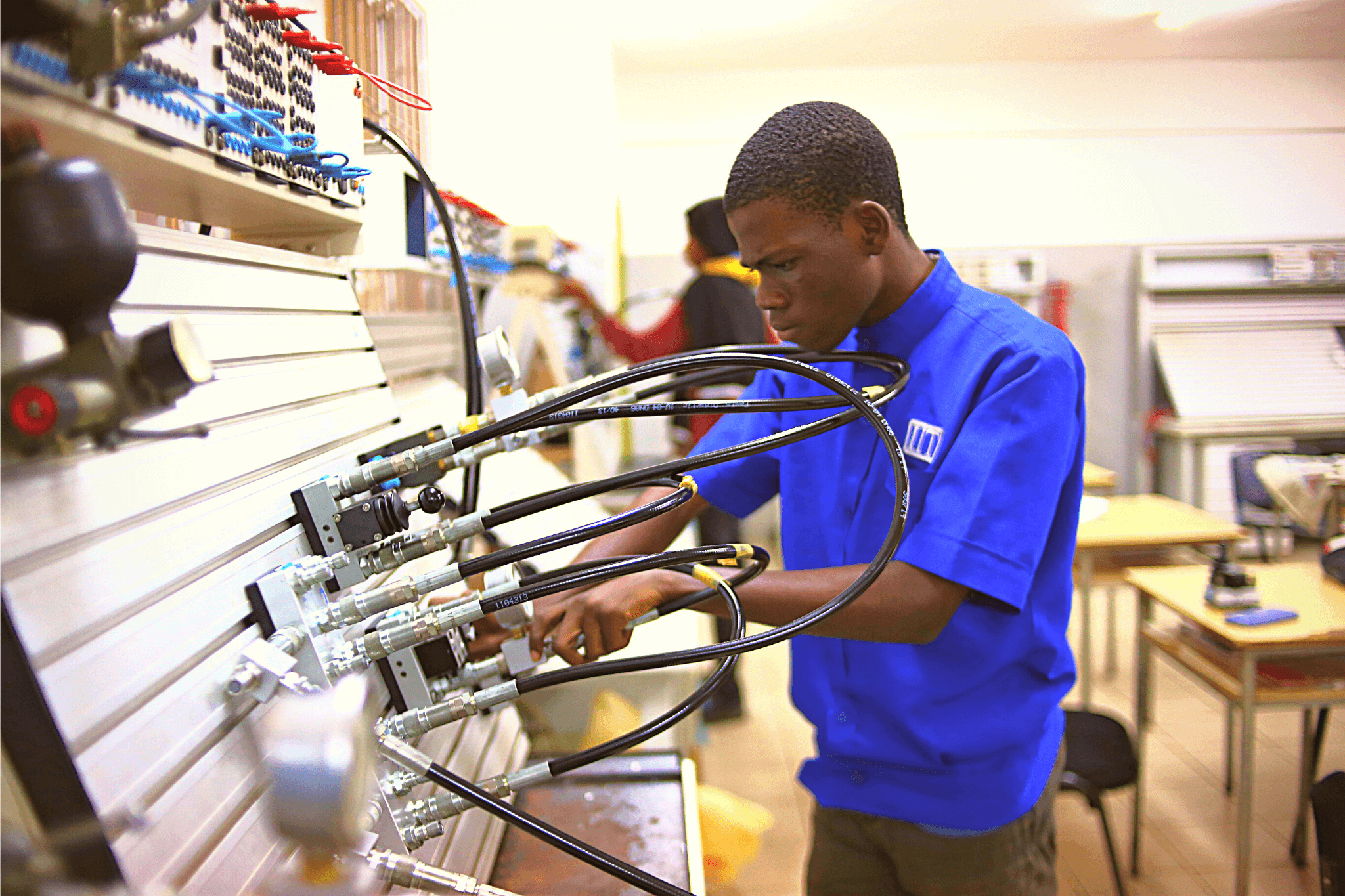

Students at the Institute for Industrial Technology in Lagos.

Nigeria is in an all-out drive for vocational education in a desperate attempt to solve youth unemployment, bridge its labour market skill gaps, and reduce reliance on shrinking white-collar jobs.

As millions of graduates struggle to get a job, the government says vocational training, funded by its novel student loan scheme, remains a future-proof alternative to theory-heavy university education.

The drive is emphasising hands-on skills in carpentry, ICT, plumbing, construction work, agriculture, CNG vehicle conversion, and renewable energy, among other vocations believed to be in short supply of skilled manpower.

Nigeria’s ministry of education looks to relaunch its technical and vocational education/training scheme in the second half of 2025, a facelift it believes would supercharge enrollment in vocational schools.

Advertisement

In Nigeria, polytechnics, monotechnics, and innovation enterprise institutes are central to tertiary vocational education.

Technical colleges, vocational enterprise institutes, skill training centres, and informal apprenticeship schemes operate at the sub-tertiary level.

The National Board for Technical Education (NBTE), which regulates vocational learning, says both private and public schools will now be drafted for a funding scheme where the young will be paid to learn and vocational entrepreneurs to mentor.

Advertisement

Schools are to be funded for tuition, and a curriculum for hands-on training is to be implemented, where master craftspeople from various industries are to be hired and paid per mentee.

This, NBTE says, will prime these schools to help align Nigeria’s human capital development with labour demands both on the domestic and global fronts.

GRIM STATISTICS

Nigeria seeks to work out a monitoring system of 774 assessors, one for each of its local governments, to oversee quality assurance.

Advertisement

The sponsored trainees, at the end of their programme, are to receive entrepreneurship grants.

Latest data from Nigeria’s statistics office, the NBS, shows that 14.5% of the country’s youth were neither in education, employment, nor training as of Q1 2024. This improved to 12.5% in Q2 2024.

In the first quarter of 2024, the unemployment rate was at 5.3%, with a subsequent decrease to 4.3% in the second quarter.

But underemployment remains a concern, with rates at 10.6% in Q1 2024 and 9.2% in Q2.

Advertisement

The informal sector continues to dominate Nigeria’s employment, accounting for 92.2% of workers in 2023.

In Lagos, Nigeria’s commercial capital, data from the ministry for economic planning and budget shows the labour market faces a disturbing paradox.

Advertisement

Monthly job vacancies average 2,837, while 3,318 individuals seek employment. About 26% of these job seekers lack both education and experience, reducing the pool of qualified candidates to 2,502.

This mismatch means employers struggle to find suitably skilled workers despite a surplus of applicants.

Advertisement

With about 1.8 million people seeking admission every year, Nigeria’s tertiary schools graduate some 500,000+ people into the job-seeking pool annually.

Universities are forced to rework their programme offerings to encourage entrepreneurship and align with changing market demands, meaning more Nigerians must explore vocational and technical fields.

Advertisement

In 2021, Collins Ojoghoro enrolled in a three-year electromechanics programme at the Institute of Industrial Technology in Lagos.

His programme ended in 2024, but he was already gainfully employed six months before graduation.

He now works as a field technician for Gottviewz, an engineering company that offers operation and maintenance services to the clients of German equipment manufacturers across West African countries.

“People study at universities for years. They then graduate and find no jobs. I didn’t want to end up like that,” the field service engineer said in a phone interview.

Ojoghoro troubleshoots electromechanical machines in beverage production lines for a monthly pay of N900,000, a rate well above the average entry-level graduate’s earnings in Nigeria.

“We say Nigeria lacks jobs, but this can only be your reality if you lack in-demand skills,” he added.

Ojoghoro is now pursuing an online undergraduate degree at the International University of Applied Sciences in Germany through its study access alliance scholarship, with plans to specialise in robotics and industrial automation.

The IIT, its programme director, David Okechukwu, said, offers programmes in electromechanics, electrotechnics, mechatronics, and engineering technology. It is one of Nigeria’s 92+ vocational enterprise institutes, which are all privately owned according to NBTE data.

“We went to Asia and Europe, studied their models, and adapted them to create a curriculum that works for Nigeria,” the IIT programme director said.

Beyond vocational enterprise institutions (VEIs), Nigeria has 135 federal technical colleges.

But a subsisting paucity of state funding and equipment shortage often means that independent private institutions are better positioned for uninterrupted vocational learning outside secondary schools.

Idris Bugaje, NBTE executive secretary, said Nigeria’s many sub-tertiary vocational schools do not offer identical certification, forcing the board to introduce the National Skills Qualification.

The NSQ framework, which will validate craftspeople in Nigeria, will be a certification tiered from levels one to nine. “This will improve the performance of vocational schools,” said Bugaje.

Globally, the World Economic Forum projects 170 million jobs to be created and 92 million to be displaced by 2030. This, it says, will result in a net growth of 78 million jobs, driven by technological advancements, the green transition, and economic shifts that will require upskilling to meet the evolving workforce demands, particularly in artificial intelligence and sustainability.

“Degrees and diplomas are now in the past,” Bugaje said. “Very soon, they will be of no value. There’s a shift towards skills. That is the reality.”

Bugaje admitted that an intervention of such scale would require a budget running into “hundreds of billions” in naira.