Yemi Farounbi’s recent article on The Church and the New Nigeria is a poignant and necessary call to action for the Nigerian church. It is an honest mirror held up to a powerful institution, urging it to reflect on its trajectory and rediscover its true purpose. I couldn’t agree more with the central thesis: the church’s focus has too often shifted from building people to building institutions. This has created a troubling paradox where Nigeria, a country with countless churches, still struggles with a crippling lack of integrity and ethical leadership.

The author rightly points out the troubling reality of corruption among professing Christians and the commercialization of institutions that were once meant to serve the common man. It’s a sobering thought that the very institutions established by the church—schools and hospitals—are now inaccessible to many. The message is clear: if the church is to be a force for a “New Nigeria,” it must move beyond simply declaring prosperity and begin to teach the faithful how to create wealth honestly and use it for the common good.

The Unspoken Elephant in the Room: The Church and Public Scrutiny

The article’s critique naturally leads to a larger, more complex question: Why is the Nigerian church consistently at the center of this kind of national discourse, while the same level of public scrutiny and criticism isn’t directed toward other faiths? After all, with a near-even split in population between the major religions, it seems like a fair question.

Advertisement

The attention on the church is a mix of historical context and the visible nature of Christian practice in the country. The early missionaries, for all their colonial ties, laid a foundation of social services that created a high degree of public expectation. The modern-day church, with its prominent mega-auditoria and influential leaders who are often seen as public figures, operates in a highly visible sphere. Its activities, from massive crusades to the public statements of its leaders on national issues, are a constant presence in the media and public consciousness. This visibility creates a kind of unspoken responsibility and a higher bar for accountability. When a leader of a major church is seen with a politician, it’s widely discussed. When a Christian is caught in a corruption scandal, it’s often tied back to their religious identity. This is a burden of its success and public prominence.

The Other Side of the Coin: The Scarcity of Critiques on Other Faiths

Now, let’s address the scarcity of articles and critiques on the role of other faiths in Nigeria’s moral and social landscape. It’s a question that many are hesitant to ask publicly, but it’s vital for a complete national conversation. While there are a few academic papers and discussions on the subject, they are dwarfed by the volume of critiques leveled at the Christian church.

Advertisement

One cannot deny the possibility of fear of retaliation, intolerance, or violence. The history of religious conflicts in Nigeria, particularly in the North, is a chilling reminder of the potential for things to escalate quickly. This creates a kind of self-censorship, where journalists and public commentators may be more cautious when critiquing a religion that has a strong and, at times, volatile political and social presence.

Another reason is the difference in how various faiths are organized and operate in the public sphere. The Christian church, particularly the Pentecostal movement, is highly centralized around powerful, charismatic figures who are often viewed as both spiritual and economic leaders. They build massive institutions that are easily critiqued for their opulence or exclusivity. In contrast, other faiths in Nigeria may be less centralized, with a more diffused leadership structure, though their scholars and traditional leaders hold significant influence. The institutions they run, while present, don’t always have the same kind of public, highly visible, and commercially driven profile as some of the mega-churches.

This isn’t to say that other faiths don’t contribute to nation-building—they do, and often in quiet but profound ways through community cohesion, education, and social welfare programs.

However, when it comes to the kind of public, moral accountability discussion that Yemi Farounbi’s article initiates, the spotlight is almost exclusively on the church. It is a reality that highlights the need for a more balanced and courageous national dialogue, one that can look critically at all of Nigeria’s powerful religious institutions without fear or favor.

Advertisement

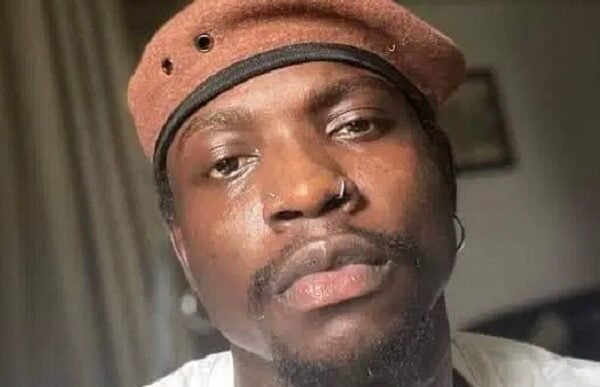

Adebawo is an accomplished business leader and communications expert with extensive experience in the oil and gas industry. He currently serves as the General Manager of Government, Joint Venture, and External Relations at Heritage Energy. Adebawo is also an author, scholar, and ordained minister, known for his writings on socioeconomic issues, strategic communication and leadership.

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.