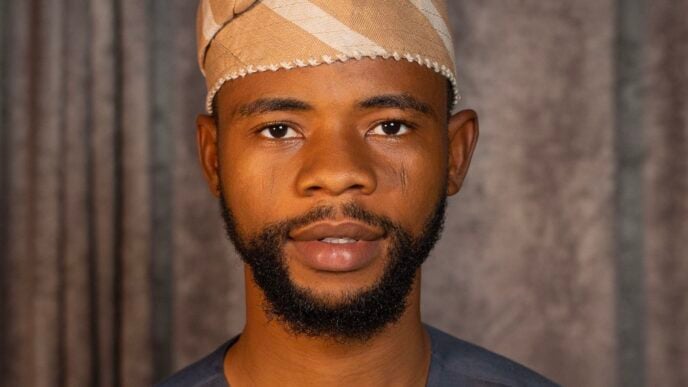

Igorigo has trouble focusing his vision. Photo credit: Claire Mom/TheCable

Joel Mohammed dragged plastic chairs across cracked concrete floors, their legs skidding noisily as he arranged them on the balcony of his temporary lodging in Utako, a commercial district in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital city. The verandah inside, where he would have otherwise received guests, was dimly lit and offered unwelcoming details about his living state than he would have preferred.

Across the door that opened into the 30-year-old’s corner, three lanky boys with bloodshot eyes sauntered into the opposite room, a thick cloud of skunky marijuana smoke wafting behind them. It mingled with the acrid stench of dried urine and stale water seeping from the bathroom on Mohammed’s end — a grimy closet of a space shared by four rooms, each divided by warped plywood boards that bent with humidity.

The old ceiling fan in his room, its blades caked with dust, whirred unevenly, helping to drive away the mosquitoes and fat black flies that claimed the damp corners as their breeding grounds. The room, rented for N8,000 (about five dollars) monthly, with its sagging mattress and water-stained walls, was nothing compared to the air-conditioned hotels in other manicured districts of Abuja. Still, it was paradise compared to the nights he’d spent in the muddy, reptile-infested thick forests of the Central African Republic (CAR).

In Lokoja, his hometown in Nigeria’s north-central, Mohammed worked as a painter, living off referrals that came only when kindness allowed. Some days, he would make roughly N7,000 (about four dollars). Once, by a stroke of luck, he earned N600,000 (nearly 400 dollars). It never happened again. Secondary school was his highest level of education, and he was determined to make sure his three younger siblings had better fates while taking care of his aged parents. But his own dreams were the price — traded daily for food, rent, and the endless demands of survival. He desperately needed a miracle.

Advertisement

When a friend mentioned a work opportunity as a labourer at a mining site in CAR with a monthly salary of 200,000 CFA (about N500,000) with a Chinese company, Mohammed could hardly believe his luck. In Nigeria, the same job paid about 80 percent less. “Why not?” Mohammed replied, especially after learning it would be an all-expense paid trip covering his passport fee and processing, travel, and accommodation.

In September 2024, Mohammed and 11 other men from other parts of Nigeria, most of whom he had no previous knowledge of, embarked on a five-day road trip to CAR to begin their new lives.

But on July 24, 2025, a viral video would paint a different picture of the promising life his family thought awaited him in the French-speaking African country.

Advertisement

IN THE FOREST, SURVIVAL WAS THE WAGE

In economics, the reward for labour is wages. But in Senye, a remote village in the Bambari region of CAR, where the miners found themselves holed up, there was practically no reward. A different kind of trade ran under their employers.

“From September to December, they gave us 7,000 CFA (about N19,000) every two weeks for food. Sometimes, it could be CFA (about N13,000),” Mohammed recalled, hunched over his hands as he stared into the distance while he sat.

According to the FAO’s food price monitoring and analysis tool, the average price for a kilogram of rice in Bambari during the period Mohammed spent in the region cost about 750 CFA; a litre of palm oil was pegged at 800 CFA; while maize was set at 200 CFA per KG.

Advertisement

The bi-weekly 7,000 CFA, Mohammed clarified, amounted to their expected 200,000 CFA wage for the four months.

In December, they were lucky enough to get 30,000 CFA (N82,000), another 45,000 CFA (N123,000) in January, and 50,000 CFA (N136,000) in February. But February’s payment would later be deducted from March’s full earnings, amounting to 150,000 CFA (about N408,000) payment in the month.

April was the only time the 200,000 CFA was paid completely, Mohammed said.

And in June, work stopped. The decision was made without prior notice.

Advertisement

“They just asked us to disassemble everything,” Freeborn Igorigo, the group’s leader, chimed in.

Living in Senye was already a struggle, and venturing into the markets was even more dangerous. Once, locals alerted the police to a strange community of “foreign men”, and the miners spent 16 days behind bars, Christmas included. They were arrested again in May while buying food, this time for being without passports.

Advertisement

Abdulmalik ‘Demola’ Azeez, a man Mohammed identified as the general manager of the Chinese mining company, had coordinated their travel from Nigeria to CAR, and from Bangui, CAR’s capital city, to Senye. The second and final time the group ever set eyes on him, Mohammed added, was in February when he asked them to bring their passports to him in Bangui for “stamping”, claiming they were about to expire.

The shortest validity for a Nigerian passport is five years.

Advertisement

Demola sent the band back without their passports, eliminating any chance of escape.

The group was unable to distinctly identify the mining company because it operated under a different name in CAR. But in Nigeria, Mohammed said he knew it as “Denaco”.

Advertisement

“Erado,” Yusuf Bameyi, 45, another member of the group, corrected.

Deneco Erado Nigeria Limited is listed on the Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC) as a company that renders mining support services. On another company verification website, one Azeez Abdulrauf Temitope is named as an official with significant control.

However, Deneco Erado is not registered under the Miners Association of Nigeria (MAN), the organisation confirmed to TheCable. Membership under MAN is a mandatory step for exploration, quarry, and mining companies, as well as service and consultancy firms related to the mining sector that either operate in Nigeria or employ the services of Nigerian miners.

Jibrin Khalid, a mining engineer and member of MAN, explained that foreign mining companies seeking Nigerian miners are required to notify the organisation. But many, he said, bypass the process and recruit unregistered local miners, leaving them exposed to harsh labour practices and exploitation.

CAR’s gold production is modest by African standards, largely driven by artisanal and small-scale miners. Yet, it remains central to the country’s resources, and the Nigerians were brought in to carve the yellow metal from virgin grounds.

The entire process is labour-intensive, requiring skilled mining engineers, geologists, technicians, and heavy machinery, including drilling machines, excavators, crushers, grinding mills, conveyor belts, and chemical treatment facilities.

None of the miners received formal training beforehand, so they leaned on whatever skills they had. Mohammed, for example, could operate a pumping machine, critical for efficient mineral processing. Igorigo, on the other hand, had previous experience in mechanical engineering. He was responsible for ensuring that the equipment ran smoothly. He could also operate an excavator — one that nearly took his life.

“I shouldn’t be alive,” Igorigo said. “Look at me. Do you know why I now wear glasses?” The reporter urged him on.

“One of the Chinese men was carelessly operating the excavator, and one of the arms flew off into the sky, hit my head, and flung me away,” he said, whirring his hands in the air like helicopter blades before stretching them as far as he could to show the impact.

“I didn’t feel it because I was dead,” he continued. “When I came to life, there was no breath.

“By the time I opened my mouth, blood was coming out of my nose, my mouth, my ears. They called it a brain hemorrhage. The distance to the nearest clinic, not hospital, was 35km. They took me there. They said I lost every sense of coordination.”

Igorigo later learned his employers had intended to cast him off at the CAR–Cameroon border. A soldier friend warned him just in time.

“Nobody likes a lazy man,” he said with a dry chuckle.

“I mustered strength, told the doctor to give me an injection to just stop the bleeding. There was blood everywhere. It was too much. People who sustain such accidents usually don’t survive.

“The soldiers took a video and sent it to the Chinese. If not so, that was how they would have left me.”

Not long after, his sight turned blurry — the reason he now wears glasses. The injury never fully healed; to this day, blood still leaks from his ears and nose. With no money for treatment, he has long since stopped seeking medical care, much against his wishes.

Obehi Akhilele, a medical doctor at St Catherine’s Specialist Hospital, Abuja, said Igorigo might need further medical attention because the symptoms suggested a possible brain injury.

“He should have done a CT scan at least to know if there was any blood clot or something because this whole connection with the eye and the blurred vision shows part of the brain is tampered with or got injured,” Akhilele said.

“The bleeding, too, is a sign that something went wrong.”

Delayed action, the doctor warned, could result in a stroke.

‘SLEEPING WITH SNAKES, DRINKING INFESTED WATER…AND SEXUAL ASSAULT’

The hunt for gold soon became a battle for life itself and a test of strength. Before mining, the group was tasked with tearing parts of the forest down to construct roads for easy access to transportation.

“They told us it was just five kilometres, but we ended up constructing a road that was almost 20-something kilometres,” Igorigo said.

“Thirty-something kilometres,” Bameyi corrected again.

Igorigo grunted briefly in affirmation and continued.

“You know an excavator cannot work from morning till the next day. So, if it works in the evening, it has to stop. I will now do the maintenance. Wherever we stopped on the road in the forest, we would have to sleep there on the floor, whether it was raining or not,” he said.

“Then, another thing again, along that road, there is no water. It’s not possible for you to see the river. So, as the mechanic, I would go and fetch a gallon of water and trek for two kilometres to go and meet the machine and top up the radiator, up to three times in a day.

“One time the engine almost knocked while they kept rushing us — work, work, work,” he said, pointing to his wobbly leg. “I had to force myself to hurry.”

With a weary sigh, he unlocked his phone and pressed play. “See the water we drank,” he said, holding it out to this reporter.

The water was a murky and unsettling greenish-yellow pool of liquid, tainted with dirt and teeming with insects. It was collected from a makeshift well, surrounded by tall grass and precarious logs that served as a bridge for the bucket used to draw the water. The trench itself may have had a faint, sickly smell.

It was just a little lighter than the pit where they worked, sifting soil and gold apart, a stagnant pool thick with mud and waste. Mohammed said snakes were often in the water. Once, it bit a colleague, but he survived.

The topic of reptiles jogged Igorigo’s memory.

“I was sleeping and a snake crawled beside me twice!” he recalled.

Yet, even that fear paled beside the alleged sexual assaults by their employers, which made their skin crawl in a different way.

“It happened so many times,” Mohammed said, his voice dipping octaves lower. “Not to me, though, to some of our colleagues.”

“When the Chinese guy came, he was telling the guy (one of the miners) to bathe him.

“Sometimes, he’d now tell him to massage him down there, until he ‘released’. The guy later reported that he and the Chinese man started to have misunderstandings.

“It usually happened after work, and it was just that particular Chinese man.”

Mohammed said the assaults followed a grim pattern: a miner endured until he complained, only to be removed and replaced with another, who was given the same orders.

When asked how many of the miners this happened to, he simply repeated “so many”, shutting down the topic.

‘WORK IS EVERYWHERE IN NIGERIA BUT DECENT WORK IS RARE’

Drawing from years of experience, Khalid said he had seen numerous cases where locals were ferried out of the country and exploited for work.

But Abdur-Rahman Balogun, director of media, public relations and protocols unit at the Nigerians in Diaspora Commission (NiDCOM), told TheCable that this was the first time Nigerian miners had come forward with such a haunting story of exploitation abroad.

Since its creation six years ago, NiDCOM had never recorded a case like this, Balogun said.

“I’m telling you, they were sodomised. That is why we acted immediately when we saw the viral video,” Balogun added, recounting the three-week process.

Comprehensive data on Nigerian migrants in employment is scarce, but it is clear that large numbers of skilled Nigerians continue to leave the country in search of work.

A 2024 International Labour Organisation (ILO) report ranked sub-Saharan Africa as the region with the fifth-largest share of migrants in its labour force.

A 2021 World Bank report blamed rising unemployment and a growing working-age population in Nigeria as factors pushing many youth into international migration, often through irregular pathways due to limited legal options.

According to the ILO, the majority of Nigerians active in the labour force are employed, and the employment-to-population ratio stood at 75.6 per cent as of last November. This ratio is higher for men (77.7 per cent) than for women (73.5 per cent).

But despite being employed, a significant number of Nigerian workers remain trapped in poverty. While the share of working poverty declined in the early 2010s, it has since remained stubbornly high, with a notable spike in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Last year, the ILO estimated that over 20 million workers were living in extreme working poverty, earning less than US$2.15 per day per person in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms.

Before modern relations between states, humans have always explored and transacted, Zakari Ismaila, an international relations expert, told TheCable. Ismaila, who holds a doctorate in philosophy, specialises in international law and migration.

He stressed that migration cannot be stopped, but observed that in many developing countries, employers often exploit migrant workers who enter illegally, knowing they have little recourse to justice.

Ismaila noted that labour laws, like those of the ILO, do exist. “But do we have an enforcement?” he asked.

“In most cases in Africa, as you have just observed in the Central African Republic, in Nigeria and other third-world countries, the enforcement is very weak. What is happening in the mining sector in Nigeria is something that should worry everyone,” he added.

Migrants frequently fill labour market shortages in destination countries, particularly in sectors such as mining and construction.

Ismaila said states must strengthen their domestic labour laws and establish bilateral agreements that provide explicit protections for migrants, whose work sustains key sectors of their host economies.

Nigeria has technical manpower assistance agreements (TMAAs) with some countries, which protect its deployed skilled professionals or technical experts, but protections for low- and unskilled migrant workers through bilateral labour agreements are either limited or undocumented.

“Diplomatic relations are to smooth the interaction between the nations, either economically, socially, politically, and whatever. That’s why it is established,” he said.

“By communication through diplomatic and formal channels, the two countries are able to take appropriate measures to make sure that justice is being served to these illegal migrants who are the victims now.”

In the absence of such agreements, Balogun explained that Nigerians abroad are expected to register their presence at the country’s diplomatic missions.

But this rarely happens, he added, making it difficult to protect citizens until their plight becomes public.

HOPE FOR THE FUTURE

Igorigo has lived through pain, loss, and betrayal. In 2009, a motorcycle accident left one of his legs permanently damaged. Soon after, his marriage broke down, and he was left to raise their two children alone.

Since then, he has hopped from job to job, often working twice as hard to prove himself against his able-bodied peers — yet earning far less than they do.

“I am very proud of you, Daddy, and I appreciate everything you do,” a text from his daughter read as he proudly showed this reporter.

“Everything I do is for them — my daughter, my son, and my aged mother — not for me,” he said, quickly tucking the phone back into his pocket.

Igorigo once worked for WEMPCO, another Chinese company. But he no longer sees a future with Asian employers.

“I need a fresh start. Because of our viral video, the Chinese would have now blacklisted us, and this money (the owed wages) is not going to come. We need a job to sustain us now,” he said.

“I am a professional welder as well, and I’m willing to do anything. How will my daughter go to school if I don’t work?

“Not just me, we all need jobs now.”

After the miners’ video went viral, the Chinese embassy said it had initiated an investigation into their alleged abandonment and urged the companies involved to address the matter appropriately.

Yet, the miners insist they still receive threats from the company through Demola, their recruiter, who is believed to be hiding in Abuja.

Almost three months since their ordeal was made public, no arrests have been announced.

Bameyi said he remains grateful for Nigeria’s intervention but fears their case will be quietly brushed aside — paving the way for other unsuspecting Nigerians to suffer the same fate.