Rangers saluting during their parade to mark 2025 World Ranger's Day at Omo Forest

“Take this N2,000, Papa. May Allah protect you.” Those were the last words 26-year-old Aisha recalled saying to her father, Alhassan Ishaiku, before he left for patrol that evening to Kainji Lake National Park in Niger state, Nigeria’s north-central.

The next time she would see him, he was lying lifeless in the back of a Hilux with two gunshot wounds to his head and one to the stomach. Suspected Boko Haram terrorists had ambushed him in the forest he spent most of his life protecting.

Aisha, a petty trader and mother of five, had gone to the market to buy a few items for her stall. Unaware of the tragedy, she noticed people staring as she walked through the market. No one dared to speak, until her sister called on the phone, urging her to return home immediately.

As she approached her father’s house, Aisha saw a crowd of mourners gathered. Her mother was weeping uncontrollably on the ground. At that moment, she didn’t need a soothsayer to tell her something was wrong. Her heart sank, and she fainted.

Advertisement

“Before he left for that particular patrol, he asked me to pray for him and also lend him a small amount of money for airtime. I gave him N2,000 and prayed for him,” Aisha said, fighting back tears.

“I didn’t know how he was buried. All I could remember was walking in and seeing my mother rolling on the floor weeping and saying that my father had died.”

Ishaiku, 55, popularly known as Tanko Tiger, was no ordinary ranger. He was a symbol of strength — one who faced down armed herders, poachers, and criminal gangs without flinching. His fearlessness earned him both respect and enemies. Yet, beyond the uniform, he was a peacemaker, deeply loved in his community for his role in mediating conflicts.

Advertisement

On that fateful day, Ishaiku and his colleagues had embarked on a week-long patrol across the treacherous terrain of Kemanji Oli Camp, located within the Borgu sector of the park. With just a day left before their return, they spotted a herd of cows wandering without a herder — one that raised suspicion.

Sensing danger, Ishaiku instructed his team to retreat and observe from a distance before leading the animals to safety.

Unknown to them, the terrorists had used the cows as a decoy. Hidden in the trees, the assailants opened fire on the rangers. Ishaiku, already wounded, could not flee as the attackers closed in on him. They shot him dead, while the rest of his team scattered into the bush for safety.

“He was killed in the night on Sunday, March 7, 2021. By the next day, the park went to the bush and brought back his corpse,” Aisha recounted.

Advertisement

“My father was the only one killed in that patrol. The bandits knew who he was. They asked if he was Tanko Tiger before they shot him. His death hit us so badly.”

That incident was not just a private tragedy for Aisha and her family. The incident made newpaper headlines at the time.

But beyond the headlines, little was heard of what became of the family he left behind.

BEHIND EVERY SLAIN RANGER IS A FAMILY LEFT WAITING

Advertisement

Five months before Ishaiku’s death, another family of a ranger was plunged into grief and left to mourn the loss of their breadwinner.

On that Monday morning of October 19, 2020, 17-year-old Abu Sufyan Jibrin ran home from school to greet his father, Jibrin Issah — another long-serving ranger at the park — just as he often did. But he was met with his unusual absence.

Advertisement

As he walked back to school, countless thoughts swirled in his mind. That night, Abu Sufyan and his siblings stayed awake, waiting for a father who would never return.

The next day at school, Abu Sufyan sensed something was wrong. His classmates kept casting uneasy glances his way, but no one said a word until a friend from another college came to take him home. What awaited him was a cascade of painful revelations.

Advertisement

“I went back to school worried. My mother said maybe he would come the next day. But at that time, he was already dead. We just didn’t know,” Abu Sufyan recounted.

“My dad normally comes back on Monday morning after his week-long patrol. Before 10 am, he would be at home. But that day, we waited till nightfall and no sign of him.

Advertisement

“My schoolmates who knew about the incident were just watching me. Nobody told me anything.”

Jibrin had gone on a week-long patrol with colleagues, including his best friend, Okon. The team, who were in their patrol vehicle, were ambushed by armed bandits.

As bullets rained on their vehicle, Jibrin urged his team not to run. But fearing the worst, his friend Okon bolted, only to be struck by a bullet mid-escape. He collapsed, screaming his friend’s name: “Oga Jibrin!”

The assailants demanded to know whose name he was calling. When Jibrin identified himself, they shot him and Okon dead on the spot. Their female colleague, seated in the back of the patrol van, was left severely injured as a bullet tore through her chest.

Seeing she was bleeding heavily, the bandits told Jibrin’s colleagues to take her to the hospital, but the patrol vehicle was already riddled with bullets and couldn’t move. So, they carried her on their shoulders through the wilderness of Oli Camp, blood trailing behind them with every step they took.

Satisfied with their rampage, the bandits set the patrol vehicle ablaze.

“Only my father and Okon were killed. The rest were allowed to go.” Abu Sufyan told TheCable.

‘RANGERS ARE NOW AN ENDANGERED SPECIES’

Rangers are the frontline defenders of wildlife and ecosystems. They are the unsung heroes of conservation, patrolling vast and dangerous terrains on foot, motorcycles, vehicles and boats to deter poaching, logging, and land encroachment.

Their work is broad and physically demanding, as they also play a quasi-security role of confronting armed poachers, destroying illegal camps, and often, they come under fire.

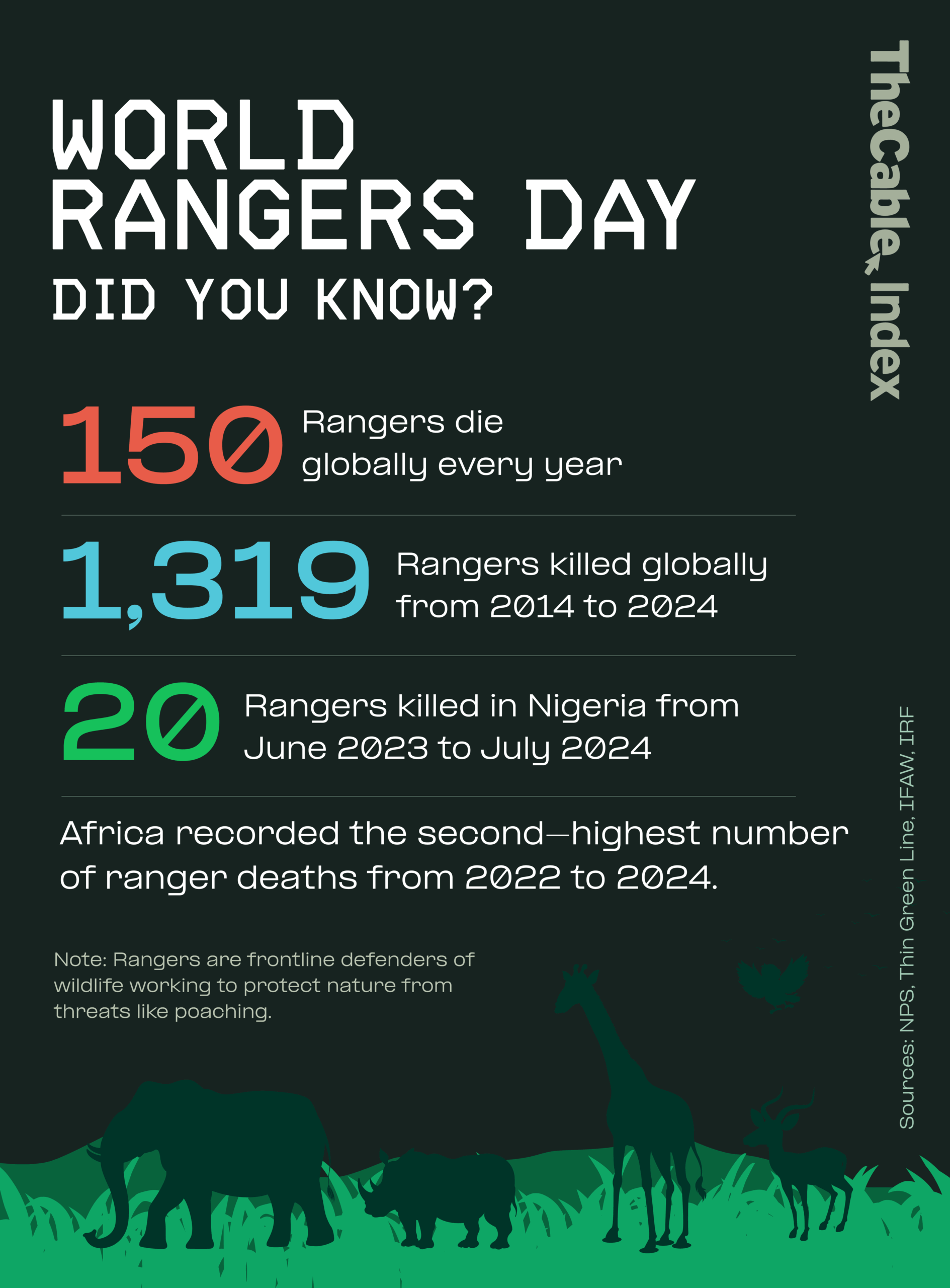

According to the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW), at least 150 rangers globally lose their lives in the line of duty each year.

These deaths indicate the dangerous reality of a job that is often underpaid, unappreciated, and poorly equipped despite being vital to global biodiversity protection.

The Thin Green Line Foundation estimates that between 2014 to 2024, up to 1,319 rangers lost their lives globally.

According to data obtained by TheCable from the National Park Services (NPS), Nigeria recorded 20 ranger deaths between June 2023 to July 2024. Most of them, killed by armed criminals.

The International Rangers Federation (IRF) roll of honour shows that Africa recorded the second-highest number of ranger fatalities between June 2022 and May 2023, with 65 deaths. Among those killed were Nigerian rangers Yahya Balarabe, who was shot while on duty, and Muraina Ayoola, who died at the hands of kidnappers.

Between 2023 and 2024, Africa retained its position as the region with the second-highest number of ranger fatalities, with 42 deaths, following Asia, which reported 74. South America recorded 11 deaths, while Europe and Central America each had six, and North America with just one fatality.

Of the 42 deaths in Africa, 16 were killed by armed bandits and poachers.

Mark Ofua, a veterinarian and spokesperson of Wild Africa, said that rangers in Nigeria are “endangered species” due to the multitude of threats they face in the line of duty.

Ofua said the work of rangers is often underappreciated despite their critical role in defending Nigeria’s forests and wildlife.

“The job of a ranger is one of the most uncelebrated and most risky jobs. Every step is fraught with danger,” Ofua said.

“They are the first line of defence for our forest resources, yet they face threats from all sides — animals, poachers, terrorists, and even their own communities.”

The veterinarian painted a grim picture of life in the field, where rangers must contend not only with animals they are sworn to protect, but also with armed bandits using reserved areas as hideouts.

He noted that rangers face grave threats from poachers and criminal elements who see them as obstacles to illegal logging and wildlife trafficking.

“The snake doesn’t know that ‘Oh, this is a ranger, don’t bite’. The wild animals, including lions, gorillas, elephants, don’t recognise them as allies,” Ofua said.

“Some forests are used as hideouts by terrorists. When they see rangers, they view them as agents of the government and attack them.

“Poachers have deliberately targeted and killed rangers. In South Africa, for instance, poachers once went after rangers just to get to the Rhinos.”

Ofua added that in most communities with vast forests and wildlife reserves, locals are not aware of the important role of rangers in conserving their wildlife.

According to him, there must be improved education and community engagement to enlighten locals about the important role of rangers in their community.

“Most poachers come from nearby villages. When a ranger arrests one of them, it’s seen as a betrayal. The community brands the ranger as an agent of oppression,” the veterinarian noted.

“These communities don’t realise the ranger is protecting their future wealth. We’ve seen it in Rwanda, where local communities around gorilla habitats now have hotels charging up to N2 million equivalent per night. They have schools, electricity, and roads. That can happen here in Nigeria, too.”

A PARK UNDER SIEGE

Spanning over 5,000 square kilometres, Kainji Lake National Park is Nigeria’s first and largest national park.

It is home to rare and endangered wildlife, including elephants, lions, and antelopes. But for years, it has also been a deadly enclave for armed attacks, illegal grazing, poaching, and transnational banditry.

A recent study confirmed that the park is experiencing an increasing level of banditry. While the exact impact of these attacks on wildlife is difficult to quantify, the report noted severe environmental consequences, including habitat destruction, illegal hunting and fishing, and a change in the status of biodiversity species.

It added that many of these threats could be prevented, mitigated or reversed through sustained national and international cooperation.

Ibrahim Goni, conservator-general of the NPS, said the government has stepped up efforts to protect Nigerian rangers from threats such as poachers, terrorists, and other armed groups.

Goni noted that the government has also approved arms bearing, special combat training, and an enhanced salary structure to ensure optimal working conditions for rangers.

The conservator-general added that the reclassification of the park service as a paramilitary agency has also bolstered its capacity to secure the country’s wildlife and protected areas.

“As an arm-bearing organisation, we are trained in many skills, including combatant skills, anti-terrorism and how to take stock of what we are managing as wildlife resource managers,” Goni told TheCable.

“We’ve received training from the army, police, and civil defence. Intelligence gathering is also key to our work. Without it, there’s nothing you can do.”

NIGERIAN RANGERS HAVE NO LIFE INSURANCE POLICY

In many countries like Nigeria, rangers work without life insurance or hazard allowance, and when they die, their families are left to struggle alone.

A 2019 survey by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF ) and the International Ranger Federation found that about 50 percent of rangers had no access to life insurance.

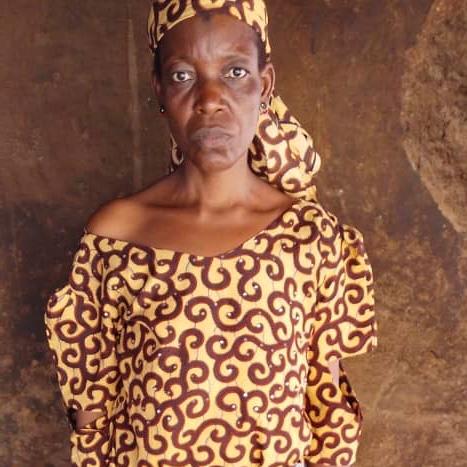

Aisha and Abu Sufyan say what stings even more is seeing their mothers struggle to provide for their families.

Aisha’s widowed mother, who now sells charcoal to feed her large family of seven, developed high blood pressure from the shock of her husband’s death.

With the burden of fending for the family taking a heavy toll on Abu Safyan’s mother, he and his younger brother took up menial jobs to support the family.

The conservator-general said the federal government has put in efforts to ensure families of fallen rangers are supported.

Goni noted that the families of fallen rangers receive at least N5 million from the government, which is expected to cater for burial arrangements and other expenses.

“The moment a ranger dies, when we get the medical report, the public service provides a window where his entitlements can be paid, like the burial allowance and all other packages. That part of the policy has just been reviewed in such a way that, at least, there is no ranger who dies in service who receives less than N5 million immediately, pending the processing of their pension and gratuity,” Goni said.

While Aisha acknowledged the support of the park service at different times, she noted that the money her family received was not up to N5 million.

She said her father’s pension and benefits have remained unpaid for four years.

“They have not paid us any pension or benefits since he died four years ago. I was asked to go to Abuja, but I don’t even have enough money to feed myself and my family, let alone pay for transport to Abuja,” Aisha said.

“I don’t have anyone to help me. If the government can hear my cry and send us my father’s benefits and pension, it will prove that he didn’t die for nothing.

“When he died, the park brought N100,000 for burial with a condolence letter. Some other time, they sent N200,000 and another N700,000 from Abuja. I have not received any other money since then.”

On Abu Sufyan’s part, he said that while the park service showed his family some support during his father’s demise, they had yet to receive his father’s pension and benefits five years after his demise.

According to him, his father had worked for over half of the month before he was killed on October 19, 2020, but was neither paid his full salary for that month nor the three months’ salary he was entitled to.

Abu Safyan also said that the park has failed to pay his father’s promotion arrears to date.

“They tried their best at the beginning. The then-conservator sent ₦100,000 with a condolence letter. Sometimes again, the park service sent about N50,000 twice and later we received support from IRF,” he said.

“But my father’s pension and benefits are still pending. His promotion arrears and three months’ payments, which should be paid to him, are still pending. What we received was only N12,000, which they said was his salary for that month he died.

“My mum insisted that we must continue our education, even if we had to struggle. None of us went to public school; she wanted to keep our father’s promise to us.”

ONGOING EFFORTS TO IMPROVE RANGERS’ WELFARE

According to Goni, the federal government has approved the paramilitary salary structure for rangers, which offers higher pay than standard civil service scales as part of efforts to motivate field officers.

He said the service is well-equipped to respond to any loss and replace manpower annually to maintain operational strength.

He added that the park service believes in inclusivity as it has women in key roles, including forest rangers, park managers, accountants, and heads of departments.

“When you lose a staff member, there’s definitely a gap. That’s why we recruit every year to replace those who retire, resign, or pass away,” he noted.

“We don’t offer special protection to women on the field because they receive the same training as the men. However, in roles that could ridicule their gender, we exercise some discretion.”

The conservation-general said the park currently deploys modern tools, including drones, GPS trackers, and the SMART (spatial monitoring and reporting tool) system, to boost ranger efficiency.

He noted that the service currently has a workforce of 2,018 rangers, with 70 percent of them deployed to the field while 30 percent handle administrative duties.

According to Goni, the service also shares intelligence with other security agencies, including the Nigerian Army, Air Force, Civil Defence, and vigilante groups.

“These collaborations help in confronting threats swiftly,” he said.

“Just last month, we trained 25 rangers who will in turn train others, making it an in-house continuous development initiative.”

CELEBRATING 2025 WORLD RANGER DAY AT OMO FOREST

Two days before this reporter arrived at Omo Forest Reserve in J4, Ijebu East LGA of Ogun state, to mark this year’s World Ranger Day, six elephants reportedly killed a man in the neighbouring Itasin-Imobin community.

Initial accounts suggested the elephants attacked unprovoked. But forest rangers familiar with the terrain said the victim was an illegal logger who encroached into the elephants’ habitat and was met with resistance from the animals defending their territory.

As the rangers led this reporter and her colleagues through Erin Camp, deep inside the forest reserve, elephant footprints marked the trails — a sign of their continued presence in the protected area.

Despite persistent threats from poachers and illegal loggers, the rangers have been working tirelessly to protect wildlife and keep the forest intact. Surveillance cameras hidden in the woods aid in tracking animal movements and spotting intruders.

The following day, the rangers marked their special day with a ceremonial parade in the evening. Dressed in crisp green uniforms and polished boots, they marched in formation, saluting their commanding officer at the full glare of spectators.

Sunday Abiodun, a hunter turned ranger at the Omo Forest Reserve, said his job has kept him away from his family and in constant danger.

Abiodun, whose wife is late, noted that he only gets to see his children seven days a month, during his leave.

“My family is not here; they are in town. My work does not give me the time and opportunity to go home and see my family. The only opportunity I usually have is when I’m given a seven-day leave in a month,” Abiodun said.

He said he stopped hunting to protect wildlife when he realised the importance of preserving endangered species like elephants and pangolins.

Despite the personal cost, Abiodun said he remains committed to protecting the forest because it is one of the few remaining places in Nigeria where elephants can still be found in the wild.

“If people are talking about where we have the most elephants in Africa, our place will be mentioned. This is a thing of pride to us,” he added.

“I stopped hunting because we were killing all these animals. Our children will not know these animals. Some adults have never seen an elephant in their lifetime.”

But protecting the forest comes with major risks. Abiodun, who remains undeterred, said rangers are constantly exposed to threats from illegal loggers, poachers, and even local farmers.

He expressed concern over the lack of support from local traditional rulers, accusing some of them of prioritising farmland over forest conservation.

Abiodun called on the state government to recognise the tourism potential of Omo Forest and invest in its preservation.

“Sometimes, farmers set traps for us. Hunters threaten to shoot us. I haven’t even mentioned the loggers who usually enter the forest at night to cut trees,” Abiodun told TheCable.

“This is the only work I have. This is what I am using to feed my family.

Emmanuel Olabode, project manager of the Omo Forest Elephant Initiative at the Nigerian Conservation Foundation (NCF), praised the rangers for their commitment to protecting wildlife

Olabode noted conservation policies need to be more effective to motivate rangers and urged authorities to support them through stronger policy advocacy and public recognition.

Back in Borgu LGA, the pain is still fresh for Aisha and Abu Sufyan.

Each day, they walk past the uniforms their fathers once wore, the photos hung on the wall, and the memories they shared, which remind them of the sacrifice their fathers paid to conserve the country’s biodiversity.

Aisha said her younger siblings, who are still in primary school, often ask when their father will return. Since their father’s demise, Aisha has become the backbone of her household, caring for her sick mother and younger siblings.

She said her mother’s medication costs ₦17,000 every two weeks, and affording it is becoming increasingly difficult without any support.

“I want the government to honour my father. He didn’t die of sickness or old age. He was killed in the bush defending the forest. He was a hero. Treat him like one.”

Until then, they wait, not just for justice, but for recognition of lives laid down in service to the country’s rich biodiversity.

This article was produced in partnership with Wild Africa.