New survey shows widespread consumption of ‘bush meat’ in Nigeria

The bush path was still wet with dew the morning 15-year-old Godwin Peter and his friend stumbled on the deer. It was a quiet Sunday, unusually so for a market day in Atte, a community in Akoko-Edo, Edo state. The boys had set out only to look for snails. But somewhere between the low shrubs and the scattered raffia trees, their dogs caught a scent and bolted.

Peter remembers the chase in fragments, his feet sinking into red earth, the clang of cutlasses against branches, the frantic barks of their two hunting dogs as they cornered the animal.

“We didn’t imagine that we could kill that kind of big animal as young boys,” he said, over a decade later. The deer, massive and worn from previous escapes, had seven bullets lodged in its body, evidence of hunters who tried and failed. The struggle to bring it down stretched for more than an hour.

When the animal finally collapsed, the boys were too exhausted to drag it home. They had to hire a motorcycle to carry the animal. The triumph, however, belonged to the entire community.

Advertisement

“We shared the meat among our families and neighbours,” Peter recalled, a soft laugh cutting through the memory. “Everybody ate from it”.

It was not a ritual offering. Not a festival or even a special event. It was simply the kind of food his family had always eaten.

“When I was growing up, we didn’t normally buy fish. I’ve been eating bushmeat since I was a child,” he said.

Advertisement

His childhood home had a shaker, a wooden rack for drying meat over slow heat. Bushmeat like rabbit, grasscutter, and antelope was the base of soups and an abundant everyday protein. Hunting was a family trade. His father and elder brothers hunted. He grew up in a community where wild animals were neither symbols of conservation nor warnings of disease but part of rural life.

Peter is 30 now, a welder living in Ibafo, Ogun state, earning between ₦500,000 and ₦1 million monthly from construction work. The teenager who once hunted with cutlasses and a catapult now buys bushmeat with the enthusiasm of a man reclaiming a familiar taste.

“I really like bushmeat more than chicken and cow meat. I buy or kill bushmeat anytime I see it or want it,” he said.

He still sets traps for rabbits and squirrels when he visits home. But in the city, he buys from roadside hunters or whoever can deliver. He said a fresh alligator cost him ₦10,000 recently. And on an average month, he can spend ₦50,000 to ₦100,000 on bushmeat alone.

Advertisement

To him, the attraction is simply because “bushmeat is natural, fresh, and stronger in protein”.

“All the chickens they’re selling now are full of chemicals and injections,” he added. Like many Nigerians, he distrusts industrially farmed meat and frozen imports. Bushmeat represents an “untainted” food from the wild, not from a factory.

As more young men like him move from villages into cities with higher incomes and old tastes, the demand for wild meat moves with them, deepening the country’s unregulated supply chains offline and increasingly online.

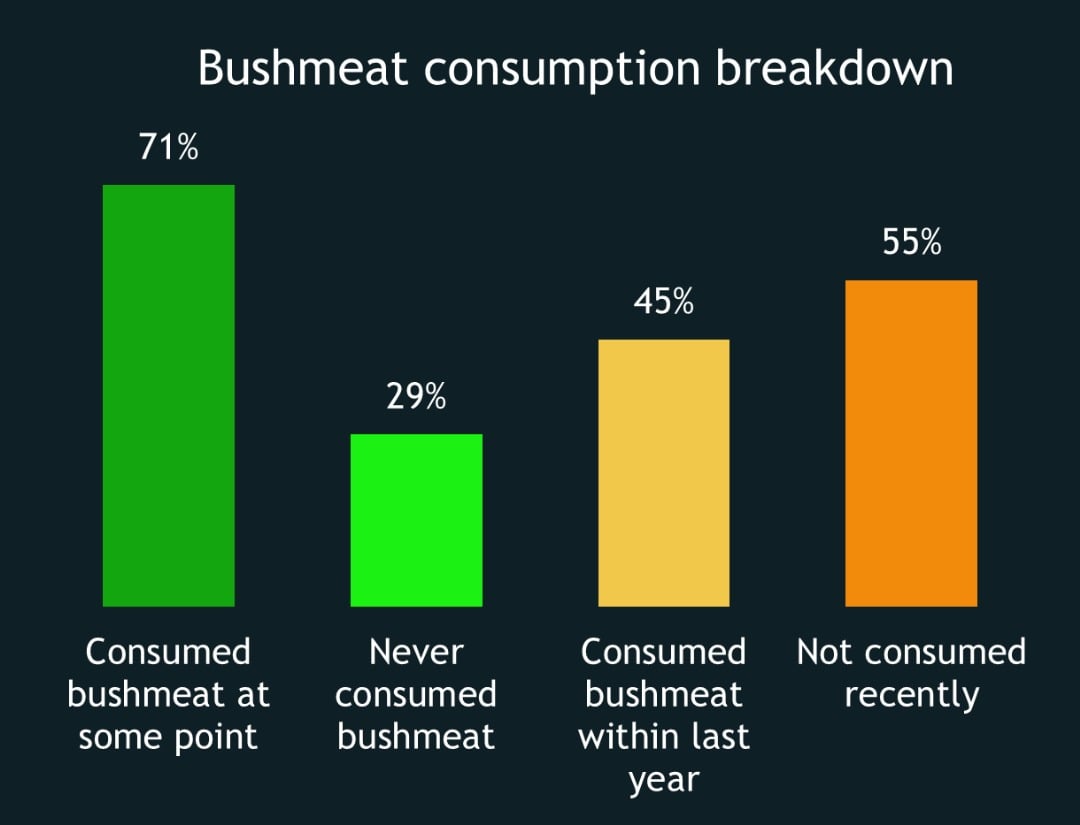

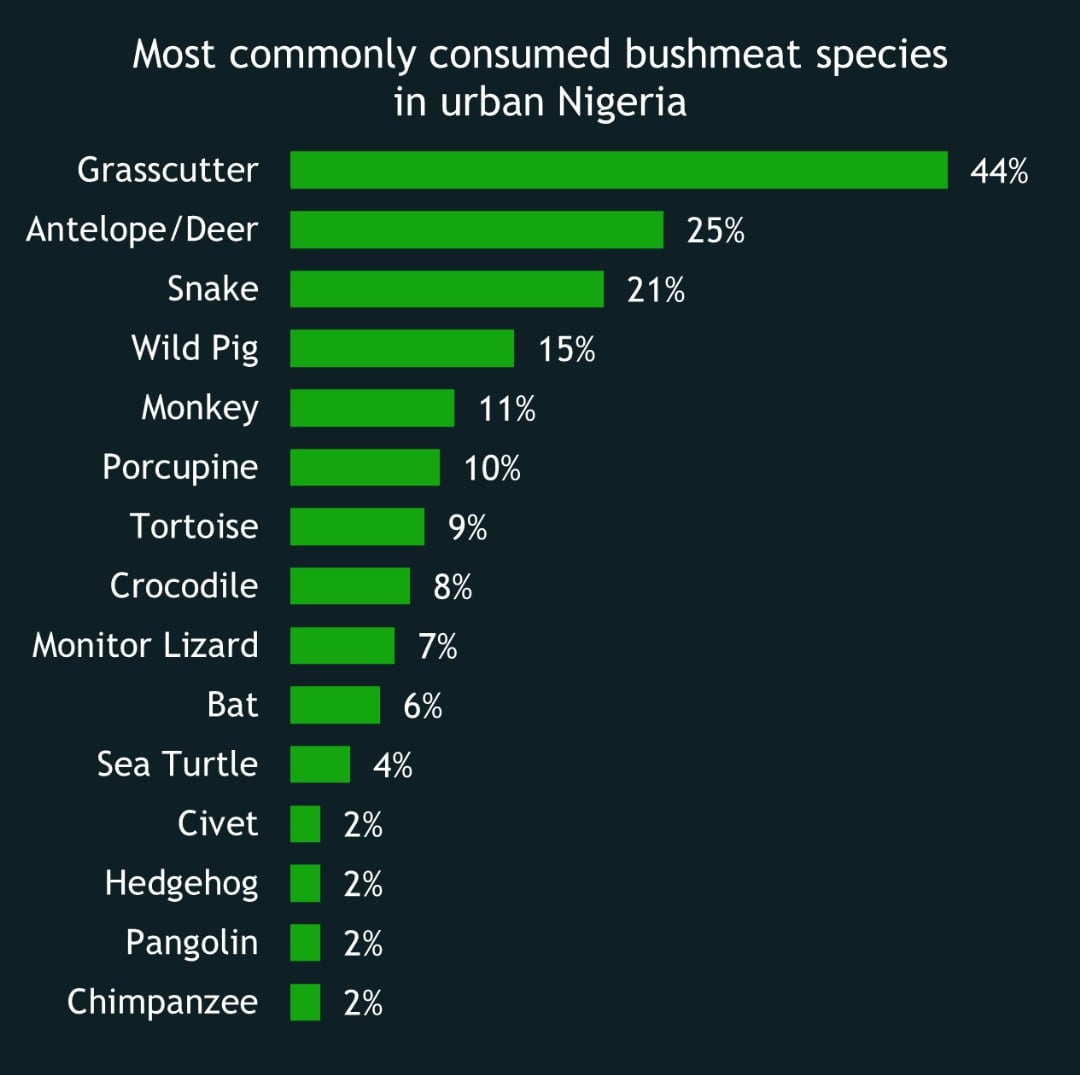

In 2020, WildAid carried out a survey of 2,000 people across Lagos, Abuja, Port Harcourt and Calabar. Results found that 71 percent of urban Nigerians have eaten bushmeat at some point in their lives, and 45 percent consumed it within the previous year.

Advertisement

Across Nigeria, the consumption of bushmeat is rising even as wildlife populations plummet. Species once abundant in communities like Atte are now scarce. The welder feels it too.

“Now, when I tell my brother to help me kill or buy bushmeat because I’m coming to the village, he complains that bushmeat is now scarce and to see them these days is very hard,” he said.

Advertisement

But scarcity has not slowed appetite. Nor have warnings.

Zoonosis is an infectious disease or pathogen that is naturally transmitted from animals (wild or domestic) to humans, often occurring when humans handle or consume the meat derived from animals.

Advertisement

According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), about 60 percent of known infectious diseases in humans and 75 percent of all emerging infectious diseases globally are zoonotic.

Research has long linked bushmeat consumption to the 2014–2016 Ebola epidemic, which killed more than 11,000 people across West Africa. Scientists traced the outbreak’s first spillover to contact with an infected wild animal. Bats, porcupines, pigs, monkeys, chimpanzees, gorillas, and antelopes have been identified as “reservoir hosts” of the deadly virus. Yet even in 2015, at the height of the crisis, Peter still ate a monkey.

Advertisement

“I didn’t fall sick. Nothing happened to me,” he said, almost triumphant.

This sense of invulnerability, combined with deep cultural familiarity and the growing convenience of online sellers, now collides with what conservationists describe as a looming biodiversity collapse, and what public health experts warn could fuel zoonotic diseases such as Ebola, Mpox, Lassa fever, and others.

INSIDE NIGERIA’S DIGITAL BUSHMEAT MARKET

In June 2022, the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development announced a nationwide ban on bushmeat sale, consumption, and transport to curb the spread of Mpox. The government ordered that the “transport of wild animals and their products within and across the borders should be suspended/restricted”.

Yet in Surulere, Lagos, Onidoko — a bushmeat spot — sits along a busy roadside where cars pass in a steady stream. The restaurant is gated, and its Instagram archive shows that the business first appeared online in December 2018.

In its early days, Onidoko sold smoked chicken, rabbit, guinea fowl, duck and turkey. The pivot came later, and not without preparation. In a 2022 BBC interview, founder Adedoyin Odunlami said it took four months of research before the team felt confident enough to introduce bushmeat and snake to the menu, and nine months before they began preparing crocodile.

Those who knew the brand knew it through social media, not by asking for directions. Its Instagram page, with nearly 30,000 followers, presents a curated world of “premium halal smoked exotic meats”: crocodile, snake, antelope, grasscutter, porcupine.

The prices, boldly listed in their posts, place the meals firmly in elite territory. Nigeria’s minimum wage is ₦70,000, but prices of snake meat at Onidoko start at ₦250,000 to ₦300,000, antelope at ₦75,000 to ₦90,000, and grasscutter at ₦80,000 to ₦100,000.

Influencers also helped push the brand into mainstream visibility. In 2022, food critic Opeyemi Famakin and digital marketer Lawal Hardcore were invited for a full-body crocodile tasting. The video, which framed wildlife meat as a luxury experience and something aspirational, drew thousands of views and inquiries nationwide.

When this reporter visited in November, the Surulere outlet appeared to be relocating. Staff wouldn’t disclose the new address. “We’re moving close by, and our new location will be announced online”, was all they offered, but the operation was still running at the half-packed site.

Five staff members were present: three men, two women. The smallest purchase available that day was a ₦16,000 peppered guinea fowl, with a prep time of two hours because “everything is made fresh”, one of the women said. Payments were strictly via bank transfer; they refused cash.

While waiting, two separate orders were picked up for delivery. In front of the compound sat a cage holding rams and a few other animals. The woman who attended to this reporter confirmed that crocodile prices started from ₦250,000, depending on size, and that the business delivered nationwide.

“Events, parties, anything,” she said. “We don’t do international delivery yet”.

The interaction felt more like a transaction at a private warehouse than a restaurant. It was discreet, controlled, and seemed insulated from scrutiny.

According to IUCN, all species of crocodilians globally face various threats, with seven species currently classified as critically endangered (facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild), four classified as vulnerable, and 12 classified as least concern.

E-commerce websites, bushmeat spots and sellers across the country freely and openly advertise wild meat on social media platforms like Instagram, X, Facebook, and even WhatsApp. This is what conservationists now fear: wildlife extraction that leaves no trail.

Mark Ofua, a conservation veterinarian and spokesperson for Wild Africa, described the online bushmeat boom as “a whole new danger” and “the undoing of our wildlife”. To him, the shift to online platforms has transformed the trade into something closer to organised crime.

Before now, he explained, enforcement officers could monitor physical markets like Epe in Lagos. “We did that successfully with pangolins in the Epe market,” he said. But the digital marketplace erased those boundaries. He noted that online sellers can hide behind aliases, delete accounts immediately after a sale, deliver straight from private homes, and hop between platforms without any trace.

“If there’s an outbreak at a physical market, we can isolate it,” he said. “But online, how do you do contact tracing?”

His concern wasn’t just theoretical. He said he had received messages from people in China and Conakry, asking to procure pangolins from Nigeria. “Somebody in China can locate somebody in Lagos, and they do a clean business,” he said, warning that the same networks “use the proceeds to fund insecurity”.

And because online sellers no longer have to bring animals to markets, no one knows how much wildlife is being taken from Nigeria’s forests.

“We are losing species without even seeing them,” he said.

Ofua also challenged a widely accepted narrative: that bushmeat consumption is driven by poverty. He disagreed completely.

“It’s not poverty per se that is driving the trade, but greed,” he said. He noted that hunters themselves rarely eat the animals they kill, noting that even the cheapest grasscutter costs more than two or three chickens.

“The only time you see the hunter eating bushmeat is because they were unable to sell it and they do not have refrigeration,” he said.

According to the conservationist, the real demand comes from the elites who can afford the prices at places like Onidoko.

“If you go to any of these hotspots, it’s the big cars that roll in, escorted by the police. It makes them feel like big men,” he said.

Bushmeat has become a marker of class identity, something people order to assert status. The dish that once symbolised village life is now a statement piece in cities and online culture.

Yet, most consumers, Ofua added, “have very little concept of zoonosis” and “very little concept of extinction”. He said illnesses linked to bushmeat consumption may emerge years later, creating a false sense of safety. “When you tell them the risk involved, they tell you they have been consuming bushmeat, and they are still alive,” he said.

THE PUBLIC HEALTH TIME BOMB

Nigeria’s bushmeat appetite is often framed as a cultural matter, a rural habit, or at worst, a biodiversity problem. But to epidemiologists, the danger sits much closer to home. Every animal killed, transported, or roasted by the roadside is a possible point of spillover.

Daniel Kolade, a One Health epidemiologist, said the warning signs have been clear for decades, even if the public rarely hears them.

“About 60 to 70 percent of infectious diseases the world responds to currently are zoonotic,” Kolade said. He said outbreaks like mpox, Ebola, Lassa fever, and even vector-borne diseases such as dengue are evidence that pathogens constantly leap between humans and animals.

Kolade explained that when people push deeper into forests and forests shrink toward people, the invisible boundaries that once kept viruses at bay begin to collapse. Poverty, culture, and expanding cities accelerate the breakdown.

He said people hunt because wild protein feels free. Farmers now plant crops deeper into forests, and young men take up trapping as hobbies or for part-time income.

“Encroachment plus economic hardship plus cultural dependence creates what we call aggressive spillover,” he said. “Hunters break that barrier and create an avenue for transmission to occur.”

Once the barrier breaks, hygiene becomes the next fault line. Many hunters butcher animals with the same knives they use at home, while some do not wash their hands. Bushmeat is often undercooked, and animals caught in one region are sold in another.

“The animal might be caught in a forest in the south, and someone buys it and travels with it to the north. Before you know it, there’s a disease outbreak,” Kolade said.

He described it as a chain reaction the country has seen before, most recently with the 2022 mpox alerts and sporadic anthrax cases in Lagos. Yet the warning has barely slowed demand.

According to Ofua, another even more unsettling reality for public health is pathogens that no longer respond to treatment.

“We are isolating resistant bacteria from bushmeat in the wild that has never seen a doctor,” the veterinarian said.

He warned that in a future outbreak, a simple infection, something that would once be treatable with first-line antibiotics, could become untreatable. He said bacteria picked up from untouched forests could carry resistance genes that undermine drugs, leaving clinicians with no effective options.

The pathogens already documented across Nigeria’s wildlife and wet markets include salmonella, pox viruses, and several strains linked to foodborne illnesses.

Ofua said many zoonotic diseases like rabies and tuberculosis are familiar. Others, like the viruses circulating in bats and primates, remain largely unstudied.

He noted that Lassa fever, which Nigerians have normalised as an annual occurrence, has killed more people in the country than COVID-19. Yet wild rodents, a major reservoir of Lassa, continue to be hunted and sold openly. The risk multiplies when you add pangolins, monkeys, and reptiles into the mix and move them between states through dispatch riders.

Bushmeat mixing in cities, he said, is “a ticking time bomb”.

Even with all this evidence, many Nigerians do not see themselves at risk. An example is Peter and his neighbours, who ate a monkey when the Ebola outbreak spread fear across West Africa in 2015.

For public health experts, this represents the gap they struggle to close: a deeply rooted belief that familiarity equals safety. If a family has eaten bushmeat for generations and no one has dropped dead, the logic goes, then the danger must be exaggerated.

But zoonotic diseases do not appear immediately. Some incubate for weeks. Some cause symptoms that mimic malaria or typhoid. Others remain silent until conditions worsen. And by the time an infection becomes visible, the animal that carried it would have long been roasted, shared, or delivered to a different part of the country.

THE SYSTEMIC FAILURES

Nigeria’s struggle to control the bushmeat trade is shaped as much by institutional limitations as by the demand for wildlife itself.

According to Kolade, the country’s biggest vulnerability lies in the way ministries and agencies operate like separate islands. He said the country’s bushmeat economy has survived because the systems designed to regulate it barely speak to one another.

At every level, from ministry headquarters in Abuja to forest-edge villages, he said the structures meant to prevent a zoonotic disaster are fragmented, underfunded, and often working at cross-purposes.

“One of the biggest gaps we have is that sectors and MDAs operate in silos,” Kolade, who leads the One Health office of the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), said.

He said this separation affects early detection of zoonotic threats because wildlife data, public health alerts, and veterinary findings rarely sit in a shared system. As a result, early warning signals — an unusual die-off in a forest community, a sudden fever cluster near a transport corridor, a new pathogen detected in wildlife samples — fall through the cracks.

Kolade explained that surveillance depends on structured, accessible data, and “without it, you cannot inform policy”.

He recommended a coordinated national system that allows wildlife officers, epidemiologists, veterinarians, and local health centres to feed into one dashboard. “If they begin to find a way to have a coordinated surveillance framework and multi-data-sharing systems, it helps cover the gaps,” he noted.

Funding also determines how far these systems can go. Kolade said many existing structures remain underutilised because there is no dedicated, consistent funding line for zoonotic preparedness. “If you don’t have access to funding, it is as good as zero,” he said.

He also pointed to the legal framework governing wildlife and public health. “A lot of them are redundant and outdated,” Kolade said, adding that legislative updates would be necessary for any long-term solution because “simply telling people to stop trading or consuming wildlife is not enough”.

The Endangered Species (Control of International Trade and Traffic) (Amendment) Act, 2016, along with other federal and state laws meant to restrict the hunting and trading of protected wildlife, has done little to influence consumer behaviour. The WildAid survey found that 54 percent of respondents believed all bushmeat is legal to buy, while 88 percent said some or all bushmeat should be legal, signalling that the existing penalties have not translated into public understanding or deterrence.

Speaking from experience dealing with wildlife trafficking, Ofua said enforcement problems persist partly because the laws guiding wildlife protection have not kept pace with the scale of the trade. “We all know how enforcement of anything is a problem in Nigeria,” he said.

The conservationist described the country’s wildlife laws as “obsolete, weak in penalties”, and “full of loopholes”. He said some of these gaps relate to ambiguous definitions of illegal possession, unclear enforcement mandates, and penalties that do not deter commercial traders.

The Nigerian Customs Service and National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA) both have mandates around the wildlife trade, but their roles often overlap and sometimes collide. Ofua said officers at both agencies are committed, but “they’ve been shackled by the extant laws”.

But even if Nigeria suddenly upgraded its laws and surveillance systems, there is the everyday reality that Peter, the bushmeat lover, described.

“How many people does the government want to be chasing or arresting?” he asked.

His question was not born of sarcasm, but rather a reflection of how deeply entrenched the reliance on bushmeat is as a critical source of both income and protein across many rural communities. According to Peter, hunting is a fallback economy for many families when farming fails, when jobs disappear, or when inflation makes ordinary food unaffordable.

A TURNING POINT IN CONSERVATION

After decades of operating under weak and outdated wildlife regulations, Nigeria is on the verge of a significant shift. The Endangered Species Conservation and Protection Bill, 2024, which passed the senate on October 28, 2025, and now awaits presidential assent, proposes clearer mandates for agencies, stronger penalties, and fewer loopholes in prosecution.

Ofua described the bill as a major step forward.“It will take Nigeria from the relegation zone in conservation to the top of the league,” he said.

He added that the bill’s defined enforcement roles, provision for judicial training, and streamlined legal processes could strengthen the country’s ability to respond to trafficking and domestic wildlife consumption.

Ofua, who also emphasised the economic dimension, said conservation must be tied directly to the financial interests of communities.

“When communities realise they stand to gain more by keeping animals alive, they won’t allow outsiders to exploit their resources,” he said. He gave the example of conservation education in schools, arguing that if children grow up understanding the ecological and economic value of wildlife, they can influence household choices.

But for Kolade, long-term progress depends on behaviour change, and he noted that this cannot be achieved through bans or warnings alone. He explained that much of the trade is driven by cultural norms and poverty. He said interventions must involve the people who rely on bushmeat, not target them from a distance.

“Most educational materials are developed for the communities, but fail to involve them,” he said. Kolade recommended messaging that uses local radio, development partners, and community champions, including survivors of Lassa fever, mpox, and other zoonotic diseases, to counter beliefs that outbreaks are spiritual or inevitable.

He also warned that government efforts will not work if citizens do not see them as credible. “If there is no trust between the government and citizens, all ideas and actions will be unproductive,” he said.

Kolade outlined what he considers essential steps: consistent public health education in rural areas; strengthening workforce capacity at state and local levels; and building a bottom-up approach where community realities shape national directives.