BY BANJO DAMILOLA AND TOLU OLASOJI

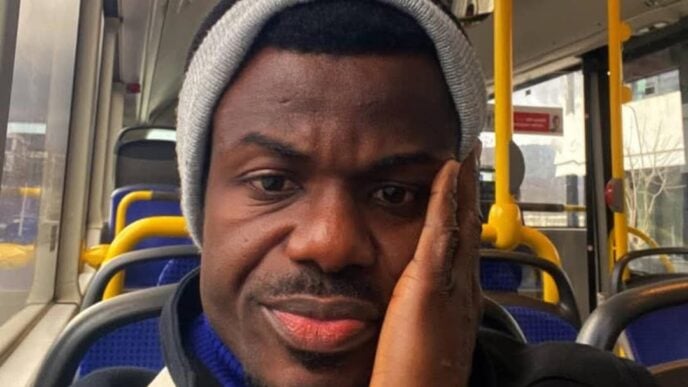

Emeka* said the lecturer called them “childish” if they resisted his advances. He would put on pornography and force them to watch, then begin touching himself. Emeka recalls those nights in vivid detail. Three boys, all under 18, living under the same roof with the man, a PhD candidate who poses as a lecturer and is known on campus as Felix,* at the invitation of parents who believed he would prime their children for university admission.

It seemed like an ideal arrangement on paper: a supposed lecturer with spare rooms, eager students from modest backgrounds, and the promise of academic success. What could go wrong? But survivors describe a year-long cycle of coercion, threats, and shame that none dared report to the police, to the University of Lagos, or even to their own families, who had entrusted them to Felix’s care.

Emeka’s recollection matches several anonymous social-media posts and other survivors’ accounts. But that’s as far as it goes.

Advertisement

He never reported what happened to him. Like many male survivors in Nigeria, he faced a culture that denies men can be victims and institutions unprepared to help them when they are abused.

Emeka’s story represents a corrosive pattern at the University of Lagos and across Nigeria, where male survivors of sexual harassment are silenced by institutional apathy and patriarchal norms. Sexual corruption, according to Transparency International, encompasses a broader range of abuses, always involving three key elements: abuse of power, the promise of a favour or advantage, and a sexual act.

Despite reforms the University of Lagos touted after the 2019 BBC #SexForGrades exposé, male students who face this kind of abuse grapple with numerous unenforced policies, societal stigma, and a justice system that dismisses male trauma.

Advertisement

Male survivors who do find the courage to seek help often encounter institutions unprepared to receive them. At the University of Lagos (UNILAG), like many other institutions in Nigeria, the infrastructure for supporting male survivors exists largely on paper.

UNILAG announced the creation of a task force as part of its renewed attention to any form of sexual abuse on campus in 2019. In a statement to the press, Taiwo Oloyede, then principal assistant registrar for communication and now the deputy registrar and admissions officer of the university, said the task force “has the mandate to examine the extant University of Lagos policy on sexual harassment, receive complaints from faculties, departments and other units concerning matters that border on sexual harassment, and recommend appropriate sanctions for offenders”.

Oloyede added that it will “put forward counselling and other therapies for mitigating the adverse effects of sexual harassment on victims” and report monthly to the vice-chancellor.

A 2017 senate-approved sexual harassment policy, reviewed for this piece, explicitly bans “unwelcome advances” between “persons of the same sex or opposite sex”, requires staff-student romantic or sexual relationships to be disclosed in writing to the vice-chancellor, and pledges a “non-sexist, non-discriminatory, non-exploitative working, living and study environment” for everyone on and off campus.

Advertisement

The policy’s six objectives include raising awareness across campus, empowering survivors, ensuring gender-neutral support, and imposing sanctions ranging from counselling to rustication, or forcing an abuser to sit out the academic year. Complaints can be submitted confidentially, orally, or in writing, with designated officers and whistle-blowers guaranteed protection.

When the University was asked for data on sexual harassment complaints that have been filed since this policy was implemented, the counselling department had no exact number.

On paper, the policy seems airtight. But a campus-wide assessment of awareness regarding sexual harassment reporting mechanisms showed significant gaps in information dissemination and institutional transparency. Earlier visits had established that while the Dean of Student Affairs office reportedly handles matters relating to student welfare, including sexual harassment issues, there was no clear indication that students use this as a channel for reporting. Students’ responses to questions about sexual misconduct on campus revealed troubling gaps in basic knowledge.

In interviews, some students appeared unsure that men could become victims of sexual corruption, while others were certain that men could not be subject to sexual harassment or corruption at all. Oluwatoyin Aregbesola, head of the University of Lagos’s counselling unit, was not surprised by the lack of awareness. Male students who are subject to sexual abuse, she said, do not always see themselves as victims of abuse.

Advertisement

None of the students interviewed on campus could describe sexual harassment reporting mechanisms in detail. None had seen posters, helplines, or signs indicating the school had an anti-sexual harassment policy, let alone one that applied to male survivors.

The head of the school’s counselling unit told PassBlue in an interview that the sexual harassment policy is available on the school website. While that is true, the important document was buried in the footer of the University’s website. Other post pages that should redirect to the school’s handbook or a revised policy held information for a webinar and a notice for course registration.

Advertisement

The official also said students are educated about sexual misconduct and romantic relationships with lecturers during the orientation week, but these reporters also found that this is not always the case. The University held its orientation for its part-time students on May 30, and there was no discussion on sexual harassment.

Several male students interviewed across different campus locations during a recent visit confirmed this pattern of limited awareness. Standing opposite the Division of Student Affairs office, Tobi recalls his student orientation proceedings focused primarily on academic expectations and procedures.

Advertisement

He has no memory of the topic of sexual misconduct being addressed. At the campus market, Vincent mentions receiving a flier that “briefly touched on” sexual violence issues during orientation, but says he didn’t retain it or any contact information it contained.

At the cafeteria, Chelsea recalls seeing awareness materials near the campus Wema Bank location, though his certainty dwindled during the conversation. A subsequent visit to that area found no such materials displayed.

Advertisement

Near the sports centre, Jude,* the most reflective respondent, pauses when asked how UNILAG addresses sexual violence. “The university has its ways of handling those kinds of issues,” he says. Like the others, he identifies the DSA office as the likely reporting channel, but adds, “I don’t personally know of anyone who had made such a report.”

At UNILAG’s Jaja Male Hostel, two students, Jeremiah and Olaiya, deflect with grim humour when asked about propositions from lecturers. “If a lecturer propositioned me?” jokes Jeremiah. “I’d collect the A first!” Olaiya nods, saying it is about navigating school life and being successful.

This pattern of awareness without direct knowledge is consistent with findings from an earlier campus visit. Interviews with staff at the Jaja Complex revealed that discussions about harassment incidents occur among students, though institutional response mechanisms remain unclear. The staff reported overhearing students discuss incidents, describing such conversations as routine, yet indicated no knowledge of protocols for reporting such matters.

Across residential areas surveyed, no posters, banners, or other visible communications addressing sexual corruption were seen.

During the discussion with university officials from the counselling unit, they described an extensive network of reporting channels, from “the VC down to even the hostel managers” and including religious leaders like pastors and imams. They pointed to a “Safeguarding Office” located at the Academic Publishing Center as the primary handler of sexual harassment complaints.

However, when asked about the task force established to report monthly to the Vice-Chancellor, Aregbesola said she was not privy to such information. This fragmentation of responsibility across multiple offices makes it difficult for students to know where to turn when facing sexual harassment, enabling a culture of silence that protects perpetrators. Although a building has been designated as the Safeguarding Office, these reporters found that it is not operational.

A 2018 study surveyed 648 students across Lagos higher institutions (including UNILAG) and found that male students reported being victims of sexual harassment, challenging assumptions about who experiences sexual abuse in academic settings. The research documented patterns of harassment that involved students gaining ‘unfair advantage, acquiring perks and privileges’; precisely the transactional dynamic that defines sexual corruption.

The Lagos State Domestic and Sexual Violence Agency (DSVA) said only 9% of 5,000 cases of sexual assault logged since 2019 involve adult males, a statistic reflecting nationwide underreporting, according to Tumininu Oni, a case manager at the agency.

These official numbers only hint at the scope of the problem, according to experts who work directly with survivors.

UNILAG’s counselling unit could recall only one case involving a male student reporting sexual harassment, from five years ago. The perpetrator was removed from the system, and the student graduated “without any molestation or fear,” according to the counsellor.

Oni attributed the low reporting among men to stigma and systemic gaslighting. “Of course, we have the stigma and the cultural silence, deep-rooted patriarchy that equates masculinity with strength and invulnerability,” Oni explained. This drives most male survivors underground, leaving policies untested, workbooks unread, and perpetrators unpunished.

Young boys from low-income communities are particularly vulnerable to sexual corruption, a form of sexual abuse rooted in exploitation and manipulation, where influential individuals promise money, gifts, or other incentives in exchange for sexual acts. In countries like Nigeria, where nearly 87 million people live below the poverty line and more than half of the child population works to support their families financially, this form of exploitation is disturbingly prevalent.

Survivors, many of them minors, are coerced into silence, either out of fear or because they have internalised the transactional nature of these abuses as a means of survival, Oni said. In 2024 alone, at least 33 boys were reported to the agency as molested by an older person. Oni said many of the sexual corruption cases reported to the agency occur within master-apprentice relationships, where the apprentice, often a boy under the age of 18, is abused and feels compelled to remain silent to keep his job.

Sexual corruption takes many forms: sometimes, victims seek advancement through sexual compliance; other times, they comply simply to maintain their basic position or livelihood.

In one case, Oni said: “The man would call [the apprentice] in and sexually abuse him. [He] will also tell him to go and bring his friends… If the boy refuses, [the abuser] is going to beat him a lot, and he’s going to tell him that he’s going to eject him from his shop. The boy was really afraid.”

In a similar case discovered by these reporters, a 46-year-old man identified simply as Ephraim trafficked a teenage boy from his home in Benue to Lagos– a journey of about 900 km, on the pretext of finding him a job. But in Lagos, Ephraim himself barely had a job. He worked as a labourer at a bakery and lived in a shared apartment that the bakery owner provided for all his labourers.

Ephraim abused the boy in the shared bakery dormitory. When the bakery owner reported the crime, Ephraim was arrested but released after two weeks. The bakery owner says he was pressured into signing a statement withdrawing the case, and the teenage boy was sent back to Benue, beyond Lagos’ jurisdiction. In Lagos, cases involving minors hinge on live testimony. “If the survivor is not around, you can’t bring anything before the alleged perpetrator,” Oni said.

Back home in Benue, the boy never told his father what had happened to him.

Amanda Iheme, a clinical psychologist in Lagos, said shame is a possible reason the boy, like many others in his situation, would not disclose his abuse to his parents. “The solution for sexual assault and abuse is silence. Forgive the perpetrator. Don’t speak about it, because if you do, you bring shame upon us,” she said, referring to the fears that plague survivors. “Meanwhile, underneath all of this, there is a little boy there who has been violated, who has been taken advantage of, and doesn’t know how to respond to it.”

Also far less helpful is the Nigerian media’s portrayal of sexual violence against men, which reveals a toxic interplay of societal taboos and sensationalism. Analyses of Nigerian dailies from the 1990s to 2010s, via the newspaper archival platform Archivi.ng, show that reports involving male survivors are often framed through homophobic tropes rather than human rights violations. Terms like “sodomized” or “homosexual act” dominate headlines, weaponising Nigeria’s cultural and legal hostility toward queerness (codified in laws like the 2014 Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act) to sensationalise crimes while erasing the survivors’ trauma.

For instance, when another 16-year-old boy was assaulted by a Lagos hotelier, Opara Macdonald, news coverage fixated on the “abominable” nature of the act rather than the violence itself. This mirrors historical patterns: a 2017 study found that 62% of Nigerian rape coverage reinforces victim-blaming myths, often burying stories on inside pages. When male survivors are mentioned, the language shifts from accountability to moral panic.

Men also respond to abuse differently depending on the gender of the abuser. Peer socialisation often reinforces the idea that sexual advances from older women are a rite of passage. However, when the abuser is a man, the response is more commonly marked by shame and silence, Iheme said.

“Shame is contagious,” Iheme added. “One person feels shame about something, you can make another person feel ashamed about that, and just like that, it continues to propagate the same way. So in the culture of men, there is no space for them to speak up about their pain, and when they do speak up, they are ridiculed and told that’s not being a man.”

Nigeria’s Violence Against Persons (Prohibition) Act of 2015 criminalises rape of all genders, yet Lagos State has not fully adopted (enforced?) it. A 2023 World Federation for Democracy report found police and courts across 12 states undertrained in VAPP’s provisions, forcing survivors into costly, stigmatising prosecutions.

While Lagos has no shelters for adult men who are survivors, DSVA has launched initiatives like the King’s Club in schools to promote “positive masculinity.” Oni urged survivors to report directly to DSVA first: “I would inform the public to make that kind of report at the agency first, so that we can provide all the necessary support from the beginning to the end.”

Despite claims of “zero tolerance” at UNILAG and assurances that “action will be taken” once the university knows of cases, the reality on campus told a different story. The same officials who tout comprehensive reporting systems acknowledge that male students suffer “in silence” and that awareness efforts consistently fail to engage this population.

With an idea of what potentially faced him, *Emeka, and the two boys who shared their stories anonymously, never took their ordeal to the police. Instead, they buried it, following the all-too-familiar script for male survivors that Iheme, the clinical psychologist, describes: “A man is supposed to get over it. You’re supposed to move on. You’re supposed to be fine.” Those expectations leave little room for a boy’s pain.

Breaking this cycle requires more than policy changes; it demands accountability and a fundamental shift in how institutions and society view and treat male survivors. Until then, stories like Emeka’s will remain buried, and the corridors of UNILAG will continue to echo with silence where there should be support.

Author’s Note: The names of students and the perpetrator involved in the sexual abuse case described in the opening paragraphs of this article were left out to protect the survivors and to encourage more students, especially male students, to come forward. It is our hope that this will give you strength.

This report was produced with support from the Journalists for Transparency fellowship, a Transparency International initiative. A version of this report also appeared on PassBlue.