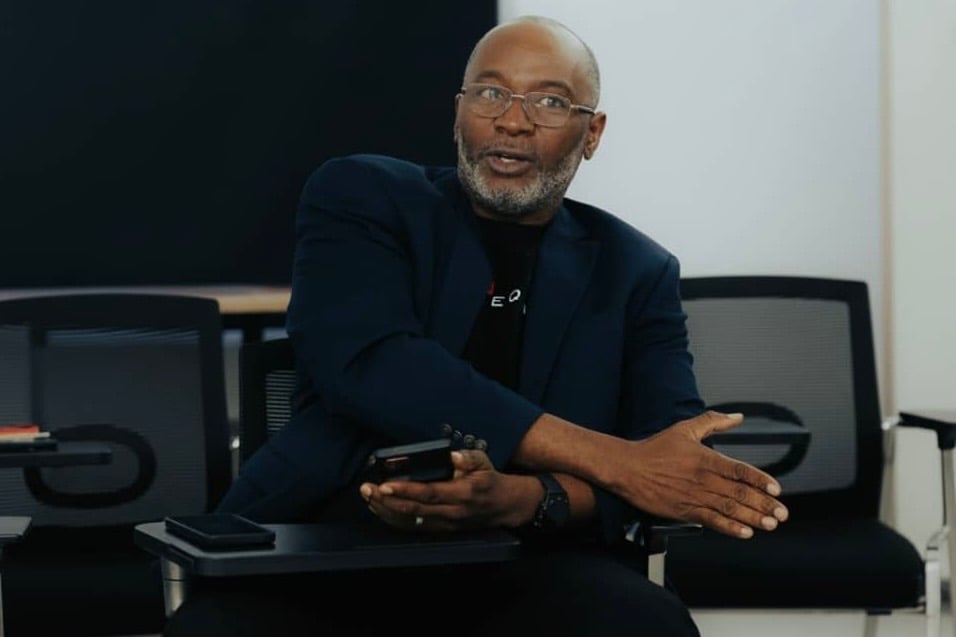

Wole Abu has spent more than two decades shaping Africa’s digital landscape – from telecom towers to data centres and, now, climate innovation.

As managing director of Equinix West Africa and founder of the One Million Trees initiative, he is at the intersection of two pressing conversations: how Africa builds the digital backbone for an AI-powered future, and how technology can drive solutions to climate change and food insecurity.

In this interview with TheCable’s AYOMIKUNLE DARAMOLA, Abu speaks on the role of artificial intelligence in addressing practical problems in Africa’s environment, agriculture, and health – areas that matter directly to the lives of the six kids he once met fighting over corn cobs on Katsina road.

TheCable: What inspired you to launch the One Million Trees Project, and why the focus on fruit-bearing trees rather than ornamental ones?

Advertisement

Wole Abu: The inspiration came from a heartbreaking moment in 2014 when I was travelling through Katsina state in northern Nigeria. After buying roasted corn from a roadside vendor, I threw my finished cob into the rubbish heap and witnessed something that changed my perspective forever – six children, no older than 9, scrambling through the garbage to fight over that leftover corn cob.

That image haunted me because I knew from growing up with domestic animals that even our goats wouldn’t eat corn cobs. Yet, here were children so desperately hungry they were diving into rubbish heaps for scraps. When I researched further, I discovered that 133 million Nigerians face food insecurity – nearly two-thirds of our population.

The focus on fruit-bearing trees rather than ornamental ones stems from a cultural observation: we’ve abandoned our African heritage of food self-sufficiency for imported aesthetics.

Advertisement

Urban elites cut down mango and cashew trees to plant ornamental plants that feed no one. Meanwhile, we import food while our year-round tropical climate could provide us with food in abundance. It’s not just about hunger – it’s about reclaiming our dignity and self-reliance. Why plant a tree that only looks beautiful when you can plant one that feeds families for generations?

TheCable: Many reforestation projects struggle with sustainability. How will you ensure these trees survive and truly serve communities?

Wole Abu: Sustainability is built into our core strategy through four pillars: Community ownership, technology-enabled monitoring, technical partnerships and economic incentive alignment.

Unlike top-down initiatives, we’re embedding trees into existing social structures. Schools where alumni associations mobilise students, religious centres where congregations take pride in their orchards, and residential areas where families directly benefit from their harvest. When people own the outcome, they protect the investment.

Advertisement

Every tree is geo-tagged and tracked through our digital platform. We’re not just planting and hoping; we’re monitoring survival rates, growth patterns, and harvest yields. This data helps us identify what works and replicate successful models.

For technical partnerships, we’re collaborating with established institutions like the Nigerian Conservation Foundation, NIFOR, and NIHORT for species selection, optimal planting techniques, and maintenance protocols. Local expertise ensures we plant the right trees in the right places.

Unlike ornamental trees that cost money to maintain, fruit trees generate income. Families and communities have direct financial motivation to care for them. We’re also exploring partnerships with food processing companies to create guaranteed markets for surplus production.

The key difference is that we’re not just reforesting – we’re creating productive ecosystems that communities depend on for food security.

Advertisement

TheCable: How are you integrating AI into the project – for land mapping, monitoring growth, or predicting food yields?

Wole Abu: AI integration spans the entire project lifecycle. We’re using satellite imagery and AI analysis to identify optimal planting locations – roadside setbacks, underutilised land around schools and religious centers, and degraded areas that need restoration.

Advertisement

Machine learning algorithms help us match specific fruit tree species to soil conditions and microclimates.

We are using it for predictive growth monitoring, computer vision and satellite tracking to monitor tree survival and growth rates. AI algorithms analyse patterns to predict which trees are thriving and which need intervention before they fail. This allows proactive care rather than reactive loss management.

Advertisement

We’re also developing yield prediction models that factor in tree age, species, weather patterns, and care quality. This helps communities plan for harvest processing and market timing.

Also, for resource allocation, AI helps optimise resource distribution – where to send seedlings, maintenance teams, and technical support based on real-time data about tree health and community engagement levels.

Advertisement

Machine learning algorithms process complex data streams to measure not just tree survival, but actual food security impact, carbon sequestration, and economic benefits for communities.

The goal is to make every planting decision data-driven while keeping the human community element central to success.

TheCable: From your perspective, what are the most practical, high-impact uses of AI for Africa today?

Wole Abu: The most transformative AI applications for Africa address our most pressing challenges, which include agricultural optimisation, healthcare access, financial inclusion, educational equity and infrastructural planning.

AI-powered crop monitoring, pest detection, and yield prediction can transform food security. With 70% of Africans dependent on agriculture, even small efficiency gains have a massive impact.

In healthcare, AI diagnostics and telemedicine can extend specialist care to remote areas. Projects using AI for malaria detection, tuberculosis screening, and maternal health monitoring are already saving lives where doctors are scarce.

Coupled with this, AI-driven credit scoring using mobile money and behavioural data is bringing banking to the unbanked. This enables entrepreneurship and economic participation for millions previously excluded from formal finance.

Personalised learning platforms that adapt to local languages and learning styles can address our educational gaps. AI tutors can provide quality education where qualified teachers are unavailable and AI analysis of satellite data, population movements, and economic patterns can optimise placement of roads, power lines, and digital infrastructure – maximizing impact per dollar invested.

The key is focusing on AI that multiplies human capability rather than replacing human labour, given our employment challenges.

TheCable: Do you believe AI can help bridge inequalities in education, agriculture, or healthcare, or will it deepen divides?

Wole Abu: AI is a tool – like electricity or the internet – that can either democratise opportunity or concentrate power, depending on how we deploy it.

AI can be the great equaliser. A child in rural Nigeria can access the same quality educational content as one in Lagos through AI-powered platforms. A smallholder farmer can get crop advice that was previously available only to large commercial operations. A community health worker can provide diagnostic accuracy that rivals specialists in urban hospitals.

But without intentional inclusion, AI will deepen inequalities. If AI systems are built without African languages, cultural contexts, or economic realities, they become tools for the already privileged.

This is why African leadership in AI development is crucial. We can’t wait for solutions built elsewhere and hope they fit our realities. We need to build AI that understands our languages, addresses our challenges, and amplifies our strengths.

The One Million Fruit Trees project exemplifies this approach – using advanced technology to solve a fundamentally African challenge through culturally rooted solutions. AI becomes a tool for community empowerment rather than dependency.

Success requires intentional design for inclusion, investment in local AI capability, and policies that ensure broad access to AI benefits.

TheCable: You have led major moves in Africa’s digital infrastructure. Why are data centres so central to Africa’s tech future?

Wole Abu: Data centres are the foundational infrastructure of the digital economy – like roads for transportation or power plants for electricity. Without them, Africa remains digitally colonised, dependent on servers located thousands of miles away.

When African data lives on African servers, we control our digital destiny. We’re not subject to foreign government policies, internet cables being cut, or decisions made in Silicon Valley boardrooms.

Data centres create entire ecosystems – jobs in construction, maintenance, security, and the countless digital services they enable. They anchor the digital economy locally.

Talk about performance and access, proximity matters for digital services. African data centres mean faster internet, better user experiences, and the ability to serve Africa’s growing digital population effectively.

Local data infrastructure enables African entrepreneurs to build solutions for African problems without the cost and complexity of overseas hosting. The parallel to physical infrastructure is clear – countries with good roads, ports, and power attract investment and enable growth. Data centres are the roads and ports of the digital economy.

TheCable: Some critics argue that data centres consume too much energy. How can they be aligned with Africa’s sustainability goals?

Wole Abu: This criticism misses the bigger picture while raising valid concerns we must address proactively. Modern data centres are incredibly energy-efficient compared to the distributed computing they replace.

One data centre powering thousands of businesses uses far less energy than thousands of individual servers. Africa has abundant solar, wind, and hydroelectric potential. Data centres can be powerful catalysts for renewable energy development, providing consistent demand that makes clean energy projects viable.

It also helps with smart integration. We can design data centres that integrate with local energy systems, using waste heat for community purposes, incorporating energy storage that stabilises grids, and partnering with renewable energy developers.

The energy cost of digital infrastructure must be weighed against the energy savings of digitalisation. Digital banking reduces transport emissions. Online education reduces the need for physical facilities. Smart agriculture increases food production efficiency.

Rather than importing energy-intensive Western models, we can pioneer tropical-optimised, solar-powered data centre designs that set global standards for sustainability. The question isn’t whether to build data centres, but how to build them responsibly as part of Africa’s clean energy transition.

TheCable: You’ve gone from telecoms to towers to data centres and now climate innovation. What ties all these together in your personal mission?

Wole Abu: The thread connecting everything is African self-reliance through infrastructure development – both digital and physical.

Telecoms connected our people. Towers enabled mobile revolution that leapfrogged fixed lines. Data centers are anchoring our digital sovereignty. Climate innovation ensures we build sustainably.

Each step addresses a form of dependency. Telecoms ended communication isolation. Digital infrastructure ends technological colonisation. Climate innovation ends environmental vulnerability.

Infrastructure doesn’t just solve one problem; it enables countless solutions. Mobile money emerged from telecom infrastructure. Digital entrepreneurship grows from data centers. The One Million Fruit Trees project leverages both digital platforms and environmental restoration.

Also, it ties into the experience I narrated earlier, having witnessed children fighting for corn cobs while we import food in a continent with perfect growing conditions, I realised infrastructure alone isn’t enough. We need infrastructure that serves human dignity and environmental sustainability simultaneously.

Every project is part of proving that Africa can solve its own challenges, build its own systems, and lead in areas where we have natural advantages – like renewable energy and sustainable agriculture. The mission is demonstrating that African solutions to African challenges aren’t just viable; they can set global standards.

TheCable: Looking ahead, what does your vision of a digitally and environmentally resilient Africa look like in 10–15 years?

Wole Abu: I envision an Africa that has become the global model for sustainable development, where digital innovation and environmental stewardship reinforce each other.

Africa with robust, renewable-energy-powered data centres in every region, high-speed internet reaching every community. AI systems built by Africans, for Africans, solving African challenges while contributing to global knowledge.

The One Million Fruit Trees initiative expanded across West Africa, with communities that were once food-insecure now exporting surplus.

Urban areas integrated with productive green spaces. Traditional agricultural wisdom enhanced by precision farming technology. Solar and wind farms powering both traditional needs and digital infrastructure, and energy storage systems stabilising grids. African battery technology competing globally.

Young Africans building tech companies that serve global markets from African bases. The diaspora returning to participate in a thriving innovation ecosystem. Aid dependency replaced by trade partnerships.

Africa demonstrating that rapid development doesn’t require environmental destruction. Carbon-negative growth through massive reforestation combined with clean industrialisation. African languages prominently featured in global AI systems. Traditional knowledge systems that inform modern solutions. Ubuntu philosophy influencing global technology governance.

This isn’t utopian thinking; it’s the logical outcome of leveraging our advantages: abundant renewable energy, vast arable land, young populations, and urgent motivation to solve pressing challenges.

The One Million Fruit Trees initiative is a prototype for this future, combining digital innovation, environmental restoration, community empowerment, and economic development into integrated solutions that work for Africa and inspire the world.