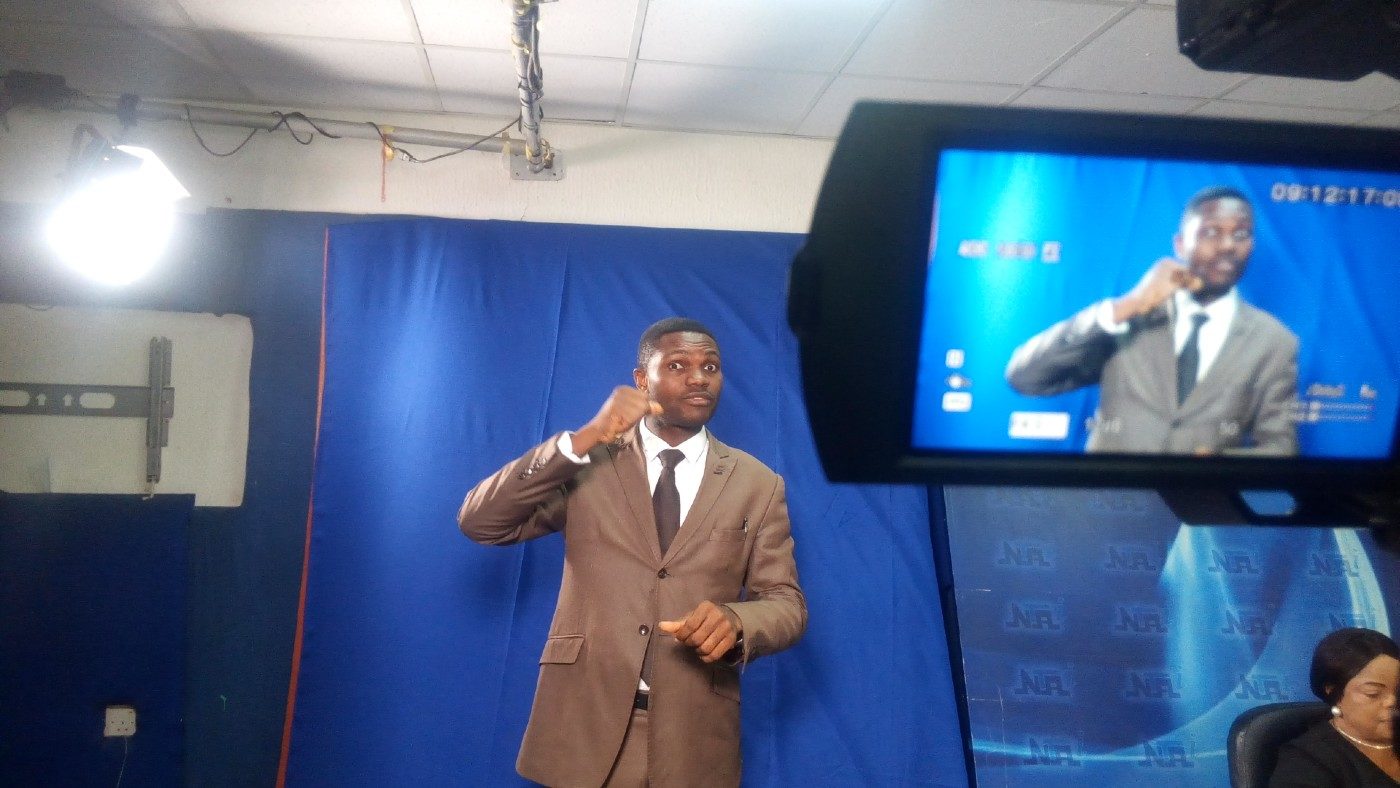

As part of efforts to stamp out malaria in 35 countries, the World Health Organisation (WHO) aims to drastically reduce its incidence and mortality rates by 2030, but insecticide resistance, dearth of innovation and investment are roadblocks to a successful outcome. In this interview to commemorate World Mosquito Day, Michael Adekunle Charles, the new CEO of RBM Partnership to End Malaria, speaks with BUKOLA AFENI on how his organisation is working to overcome some of the pressing challenges.

Can you tell us how the RBM Partnership to End Malaria is working to end malaria in Africa?

Charles: The RBM Partnership brings together over 500 partners, all united in a common goal to end malaria. With Africa accounting for 95% of all global malaria cases, our work across the continent is of course a crucial priority.

Importantly, the RBM Partnership works closely with malaria-affected countries and partners in Africa to help optimize the quality and effectiveness of country and regional programming. In practice, this means working with national malaria control programmes and wider stakeholders to design quality programmes that are informed by the latest data, tailored to the local context, maximize local capacity, and bring in wider stakeholders to ensure malaria control is prioritized at all levels.

Advertisement

Another important role we play is ensuring levels of funding for malaria programmes are maximized and mobilizing new resources for the fight against malaria. We therefore work at both the global and national levels to ensure malaria is high on the political agenda. Our working groups also bring together partners with technical expertise to tackle malaria challenges, including case management, malaria in pregnancy, and vector control.

Through the delivery of preventative tools, like insecticide-treated nets and anti-malarial medications, investment in research and development, and amplifying the urgent need to ramp up the fight against malaria, the RBM Partnership to End Malaria is committed to making a difference in Africa’s fight against the disease.

How are you collaborating with other development partners to ensure that insecticide-treated nets are made available to remote communities in Africa?

Advertisement

Charles: Insecticide-treated nets are a fundamental prevention tool, making a significant contribution to the 11.7 million lives saved from malaria through global partnership and sustained investment at the start of the century. In 2020, partners celebrated the distribution of two billion nets, however, more must still be done to reach the 53% of people in sub-Saharan Africa at risk who still do not sleep under one. We therefore work closely with our partners and malaria-affected countries to ensure nets are deployed efficiently and effectively, implementing a range of strategies – such as our Malaria Matchbox tool – to reach the most vulnerable communities.

Sadly, today insecticide resistance also threatens the effectiveness of standard nets, and so we also are also working to help facilitate the deployment and scale-up of new, innovative tools. For example, the New Nets Project, funded by partners including Unitaid and The Global Fund and led by the Innovative Vector Control Consortium (IVCC), has trialled the use of dual-insecticide nets across 17 countries between 2019 and 2022 to combat the growing threat of insecticide resistance.

Can you explain other means of preventing malaria, especially among people living in remote communities in Africa?

Charles: In addition to the delivery of insecticide-treated nets, there are several other means for people living in remote communities in Africa to protect themselves from malaria.

Advertisement

One key strategy is the use of preventive medicines. In Africa, several countries are now offering Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention (SMC) to children under 5 – who are particularly vulnerable to malaria – ahead of the rainy season when transmission is highest. The average number of children treated per cycle of SMC increased to almost 45 million in 2021. It is also important that pregnant women, who are also highly vulnerable, receive at least three doses of a preventive treatment known as IPTp during their pregnancy.

A number of countries in Africa are also now starting to roll out the world’s first malaria vaccine, RTS,S following WHO’s approval in 2021, alongside existing tools. More than 1.2 million children have already been protected by the RTS,S vaccine across Ghana, Kenya, and Malawi through initial pilot programmes.

People living in high-risk areas can also follow some simple steps to keep themselves and their families safe from malaria, including keeping areas clean and clearing stagnant water to prevent breeding grounds for mosquitoes. It’s also important that people living in malaria-endemic regions seek diagnosis as soon as possible when presenting with a fever, to receive rapid treatment.

What innovative solution is your organisation bringing to tackle the issue of mosquito-borne diseases?

Advertisement

Charles: Recent investments in R&D have produced the most robust pipeline of malaria interventions in over a decade to address emerging threats and transform the fight against malaria – from new nets, vaccines and medications to potentially transformative approaches such as gene drive technologies. Despite remarkable progress, however, many proven interventions are waiting to be implemented at scale. Urgent investment from the public and private sectors will be required to accelerate innovation and deliver transformative and improved solutions to end malaria.

We also bring together our partners to facilitate peer learning on delivering or implementing new tools or approaches through the sharing of experiences, lessons learned and best practices.

Advertisement

How would World Mosquito Day aid in creating awareness geared towards ending malaria?

Advertisement

Charles: Unfortunately, the ability of the Anopheles mosquito – and the malaria parasite it transmits– to constantly evolve has given rise to emerging drug and insecticide resistance, reducing the efficacy of existing tools including insecticides, antimalarial treatment and rapid diagnostic tests.

World Mosquito Day is however an opportunity for us to raise awareness of the dangers of malaria-carrying mosquitoes, and to shine a spotlight on the ongoing research and innovations aiming to stay a step ahead of the constantly evolving mosquito.

Advertisement

How does the ‘Zero Malaria Starts with Me’ movement support the RBM Partnership and African Union’s goals to end malaria in Africa?

Charles: Zero Malaria Starts with Me is a movement dedicated to empowering communities to take ownership over the fight to end malaria, driving action at all levels of society including among political, private sector and community leaders to accelerate malaria prevention and treatment and save lives.

The RBM Partnership to End Malaria and the AU Commission announced the launch of the pan-African Zero Malaria Starts with Me initiative back in 2018. Since then, 27 countries in Africa have launched national campaigns. Other AU Member States affected by malaria have also committed to launch national campaigns by the end of 2023.

Through the Zero Malaria Starts with Me campaign, countries are also increasing multisectoral action and domestic resource commitments for the disease. Six End Malaria Councils have been launched to date to drive multisectoral action at the national level, supported by End Malaria Funds to mobilize domestic funding from new sources for the fight against the disease. Since 2020, five African countries have also introduced the Zero Malaria Business Leadership Initiative in collaboration with Ecobank to drive private sector engagement for the fight against malaria.

SDG 3 is centred around ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all ages. Do you see the African continent ending malaria by the year 2030?

Charles: In line with targets set by the World Health Organisation (WHO), we are aiming to reduce malaria incidence and mortality rates by at least 90 percent between 2016 and 2030 and eliminate the disease in 35 countries.

Today, however, low coverage of existing tools, emerging biological threats and funding shortfalls are brewing a perfect storm for malaria.

We urgently need decisive action to deliver on our goal of zero malaria and achieve 2030 targets. To do this, global leaders, malaria-affected countries and partners must urgently invest in programmes, innovate to develop and tailor new tools and approaches to those who need them most and implement national strategies to accelerate progress against this age-old disease.

Add a comment