The memorial stone bearing the names of 18 deceased victims

On March 15, 2020, a deadly explosion shattered Soba Community in the Abule-Ado area of Lagos state, claiming several lives. Official reports blamed the blast on activities along the right of way (ROW) of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) pipeline.

Five years later, encroachments have resurfaced, rekindling fears of another tragedy. What lessons were learned? What promises were made, and broken? Why is history repeating itself?

In this investigation, TheCable returns to the scene of one of Nigeria’s most devastating urban explosions and uncovers how influential government agencies and local actors are colluding to perpetuate a silent threat in a disturbing pattern of neglect, impunity, and corruption.

One hundred and eight! That was the number of stitches Oyerinde Damilola’s body bore after she was flung from the front of her church as a blast ripped through and destroyed 100,000 square metres of a Lagos community in March 2020.

Advertisement

“I was putting on a yellow dress; it soaked my blood till it turned red,” Damilola said, recounting how the force threw her through the church’s glass window across the road. She now lives with the scars and partial blindness in one eye from the incident that her 18-month-old daughter also survived. However, 23 others did not – many of whom are now memorialised on a tombstone.

Davidson Obi Iyooh, Oby Lilian Iyooh, Kachi Iyooh, Tochukwu Ani, Festus Ose, Emmanuel Onyemaechi, Chisom Jesofa Uyamadu, Chinenye Uyamadu, Monday Agbo, Funke Edet, Ali Bayoburi, Salisu Abdullahi, Ibrahim Adamu, Sani Ubale, Auwulu Isah, Kabiru Muhammed, Isah Ali, and Sama Ila Sallaui.

“In memory of our fallen heroes to the pipeline explosion in Soba Town, Lagos on 15th March 2020,” the tribute reads.

Advertisement

The Lagos State Emergency Management Agency (LASEMA) said 276 people were displaced and 268 students were affected by the incident. It confirmed 70 rescued, 23 dead, and 25 injured. It reported 170 houses were damaged — 93 slightly, 44 moderately, and 33 severely. The incident also destroyed 40 cars, three articulated vehicles, three churches, seven schools, a hotel, and a shopping complex.

Five years on, around the memorial stone which sits a few metres from the explosion epicentre, the warning signs are back. Commercial activities have resumed on the NNPC pipeline ROW. The military taskforce charged with protecting it is instead accused of benefiting from the lease of the corridor. At the same time, the Lagos State Building Control Agency (LASBCA) has turned a blind eye to encroaching structures.

WAS IT A BOMB, PIPELINE OR GAS CYLINDER EXPLOSION?

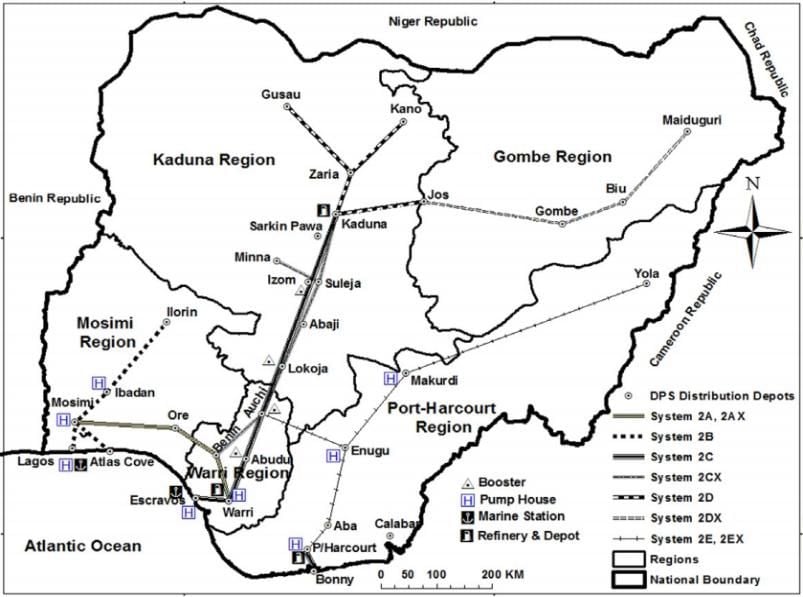

The explosion was first thought to be a bomb, although findings later showed that beneath the affected community runs the System 2B pipeline — part of a 5,001km national network. This immediately drew NNPC’s attention.

Advertisement

System 2B: Key Facts

- Serves the entire southwest, from Atlas Cove to depots in Mosimi, Ibadan, and Ilorin.

- Designed between 1978 and 1980 with a 25-year lifespan.

- Accounts for 70% of service gateway for Nigeria’s oil product importation.

- In 2019, NPSC planned to expand System 2B to service Nigeria’s north-west.

The NNPC had blamed the blast on encroachers. Kennie Obateru, then spokesperson of NNPC, said the explosion was triggered when a truck hit gas cylinders at a nearby plant, while Mele Kyari, the agency’s CEO at the time, urged residents not to build on the pipeline corridor as it is “very dangerous and they should respect our right of way”.

But a BBC investigation later found this to be misleading and revealed that the NNPC pipeline was compromised when a granite-laden truck (weighing about 25 tonnes) sank directly atop the pipeline, cracking the infrastructure and releasing flammable vapour, which ignited.

The reports were corroborated by residents, although the agency stuck with their narrative and never revealed who owned the truck in question or the gas plant operators, or whether any individuals were identified or prosecuted.

Advertisement

Philips Akinduro, vice-chair of the Soba Landlords and Residents Association (SLARA), believed pressure from gas flow ruptured an “already weakened pipeline”. The community has sued NNPC, Akinduro explained, adding that the case remains pending at the Ikeja high court.

Regardless of what ignited the explosion, one fact stands: the tragedy stemmed from violation of the pipeline ROW, and now, there are fears disaster looms again as activities including a bar, carwash, block industry, supermarkets, metal recycling scrapyard, among other businesses have occupied the ROW.

Advertisement

POORLY MARKED PIPELINE CORRIDORS

The NNPC, through its subsidiary, Nigerian Pipelines and Storage Company (NPSC), is charged with maintaining its pipelines, with the Petroleum Pipeline Regulations 2022 mandating clear ROW markers and regular patrols to “detect encroachments” or hazards that “may endanger the safety of the pipeline.”

Advertisement

TheCable found this to not be the case during a recent visit to Soba, where some pipeline markers have faded and are hard to recognise. Some of the markers, residents said, have also been removed by scavengers.

“It’s not even a signboard. Who will know what it means if it’s just an iron bar and not painted?” Akinduro queried.

Advertisement

MILITARY COMPLICIT IN ILLEGAL LEASING OF ROW

TheCable learned of instances of alleged corruption and impunity by some personnel of Operation AWATSE, the military joint task force established to combat pipeline vandalism.

According to several residents, the taskforce, which failed to prevent or report the initial encroachments leading up to the 2020 explosion, is now exploiting the system and profiting from the illegal leasing of the pipeline ROW to businesses for backhanders.

They alleged that negotiations typically begin with members of the Baale’s (traditional ruler) family and are concluded with military backing. Several business owners on the ROW confirmed that such transactions have been ongoing for some time.

Residents also spoke of how the military officials, stationed just by the roadside, extort truck drivers and cart pushers transporting building materials and other products along Soba road.

“You go to them and drop ₦100 in a bowl. If not, they make you cut grass,” said *Salisu, a cart pusher.

To date, the military outpost’s roof has not been repaired since it was torn off by the blast, the sole visible reminder of the incident in that area.

Commenting on the repeated attacks and explosions along the System 2B Pipeline, Kyari, in 2020, acknowledged that “there are compromises within the NNPC, the security agencies, communities”.

“What we have done in the last two months is work with these agencies and NNPC to make sure that we take out the bad elements out of us, resolve this issue and delete them if we need to do that and that is what we will do,” Kyari said.

The leadership of Operation AWATSE initially told TheCable it was unaware of these developments and promised to investigate. It later gave feedback confirming “some encroachments on the right of way”.

“Action is already activated to deal with the incursion and those that allow it,” Dave Raji, a representative of the operation, told TheCable.

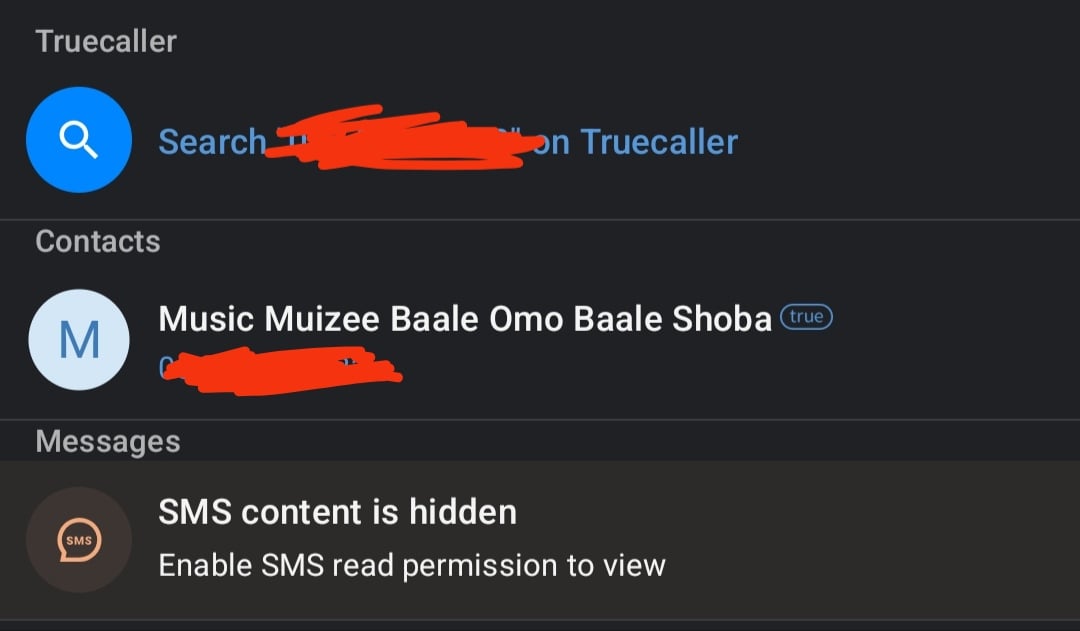

ROW ‘FAST SELLING’ AT N400,000 FOR A PORTION OF LAND

To unravel how the land leasing deal is done, the reporter, posing as an interested buyer, contacted a dealer simply identified as Muiz, who sources said was part of the cartel running the deals. A Truecaller search of Muiz’s phone number showed “Muizee Omoo Baale Shoba”, a Yoruba phrase which means “Muizee, Shoba traditional ruler’s child”. This corroborates earlier reports of the involvement of the Baale’s family.

After enquiries about the proposed business venture on the land, which the reporter identified as the sale of bottled water and soft drinks, Muiz met with the reporter on July 5 alongside a colleague of his and offered a tour of sections of the ROW for lease, showing some already occupied.

He then charged ₦500,000 as the cost of lease for a portion of the area, defending it as needed because “there are people that will collect money — soldiers and boys”. He eventually agreed to ₦400,000.

“We settle the soldiers and the boys so there won’t be any problem,” Muiz said. “They’re here for security. That’s why we settle them…we are all together.”

After accepting ₦3,000 in cash as a “commitment fee”, Muiz promised to provide an agreement document and receipt upon payment for the land.

“We show this place to a lot of people every day,” he said. “We will stand by you that we were the ones who leased you the land. This place is fast-selling. I don’t call people back!”

The community, Akinduro said, had unsuccessfully tried to intervene and dislodge businesses on the ROW. He explained that in one case, the Community Development Association (CDA) attempted to evacuate a metal scrap yard located near the pipeline. However, he said the move was thwarted by a military officer, who allegedly apprehended him for questioning, while threatening to open fire on his team if they did not retreat.

“We have tried as much as possible to eject encroachers, especially those with block industries. Many times, I’ve gone to talk to them because that machine they use vibrates the earth,” he said.

MARKED BY LASBCA BUT STILL STANDING

Along the ROW were some shops marked for demolition in May by LASBCA. A month later, instead of the expected demolition, construction work continued and the structures were plastered and nearing completion.

Residents and survivors of the 2020 blast were shocked by the seeming impunity, especially after being told no structures would be allowed in the area.

“We wanted to fence the place to demarcate that this land belongs to us, but we were told the government said no activities should happen there,” said *Rachael, one of the survivors of the blast whose family’s land at the site has been overtaken by plastic collectors.

On July 1, the reporter visited the LASBCA district office in Amuwo-Odofin and met with an official, Adegbayi Olowu, who acknowledged that the agency is aware of the structures in question.

“We’ll investigate and do the needful,” Olowu said.

Two weeks later, he confirmed that notices had been served on two uncompleted buildings and a supermarket.

“We’re expecting them to present whatever documents they have,” Olowu said.

When asked why the buildings were initially marked for demolition, Olowu said investigations were ongoing and advised the reporter to visit the office in person for further clarification.

Adu Ademuyiwa, LASBCA’s spokesperson, is yet to respond to the questions provided upon his request.

PROMISES, PROBES REMAIN PENDING

While government officials and state actors — those duty-bound to safeguard the ROW– are busy lining their pockets, the shattered victims of the explosions remain trapped in grief, still counting their losses and nursing wounds that run far deeper than the eye can see.

One of such victims is *Clement, a septuagenarian, who left home as a landlord to attend the 9 am mass at St Joseph Catholic Church, but returned as an IDP. His one-storey building collapsed from the impact of the blast. He and his family would spend the next five years in a room at a friend’s house.

Despite documentation, Clement said he received “not even a naira” in support or compensation from the government.

After the blast, the Lagos state government set up a ₦2 billion relief fund chaired by deputy governor Obafemi Hamzat; ₦250 million was deposited by the state. Donations included ₦2 million from the Rotary Club and ₦200 million from Nigeria’s governors’ forum.

Zenith Bank donated N100 million, while Dangote Cement donated cement worth the same price.

The state government said it settled the initial hospital bills of injured residents, sheltered over 100 displaced persons for six months, and fixed power supply in the community.

Some relatives of victims confirmed receiving ₦2.5 million per deceased family member, but survivors said they largely bore their medical expenses and got no support for their destroyed buildings and properties.

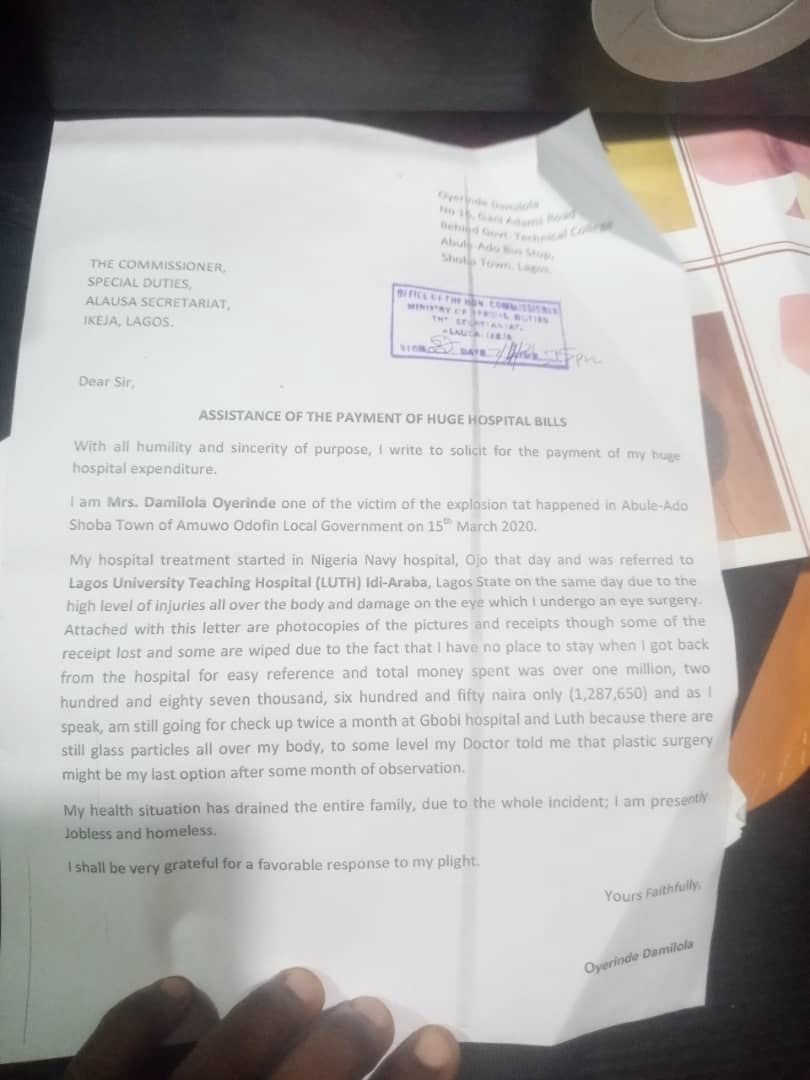

Damilola said she spent over ₦1 million on her eye surgery and other treatments at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH). She visited the government secretariat in Alausa multiple times, submitting receipts and photo evidence — all acknowledged, but no assistance followed.

The mother of two said the cost of treatment plunged her family into deeper hardship, as her husband had to use his business capital to cover her medical needs.

By the time she returned home from the hospital, the COVID-19 lockdown had begun, forcing her to rely on a home doctor.

“I removed all these stitches myself. I couldn’t go back to the hospital,” she said.

Segun Oyerinde, her brother-in-law and the church’s lead pastor, said the incident “brought sudden death to my dad”. Fighting back tears, Segun condemned what he described as reckless disregard for residents’ lives, saying that despite the dangers of building around the pipeline, people continue to encroach while the military and NNPC patrol teams reportedly turn a blind eye in exchange for payments from encroachers.

He also questioned why Bethlehem Girls’ College was relocated to a new site, while other residents who lost their homes received no such support.

During the first memorial anniversary, Segun Idris, a member of the probe committee set up the Lagos state government and then vice chairman of Amowu Odofin LGA, said through the committee, the government had decided to build a “befitting” access road, fire service station, water system, health center, a LASTMA post, and a town hall for the community.

However, none of those promises have come to bear in Abule-Ado. The state has yet to explain how much was raised or how it was disbursed.

Meanwhile, there are no public records available on the findings by the committees set up by the Lagos state government, senate, and house of representatives to investigate the causes of the explosion.

TheCable reached out to Gboyega Akosile, Sanwo-Olu’s spokesperson; Gbenga Omotosho, the state commissioner for information; and Samson Adebayo, media aide to the deputy governor, for information on how much fund was received and expenditures made.

Akosile did not respond. Omotosho acknowledged the inquiry but gave no feedback. Samson declined to comment.

TheCable also shared its findings with Aliyu Abubakar, media assistant to the NNPC GMD, but has yet to receive the feedback he promised.

WHY PIPELINE ENCROACHMENT PERSISTS DESPITE REGULATIONS

Ambisisi Ambituuni, a pipeline safety expert and associate professor, says little has changed since his co-authored study on a section of the System 2B.

The study noted “inadequate maintenance of the pipeline ROW and encroachment of buildings” could increase the vulnerability of the pipeline to third-party activities and increase its incident rate values.

“And I would not be surprised if you find exactly the same thing that I found 10 years after I did that research. If any, I would assume that things have gone worse. The NNPC is not known for a maintenance culture anyway,” Ambitunni told TheCable.

He described the regulatory environment as deeply compromised, where enforcement officials are driven by short-term interests, allowing public infrastructure to be repeatedly violated without consequences.

According to him, a key driver of pipeline encroachments in urban areas is the perception that government land is accessible and unprotected.

On whether the NNPC adequately communicates risks or engages host communities, Ambituuni said that though he has seen attempts, they are insufficient.

The gap between the official account and independent evidence, as seen in the Abule-Ado situation, reflects a common tension in safety-critical sectors: the impulse to protect institutional reputation often overrides transparent risk communication.

Experts have noted that such framing limits public scrutiny and delays meaningful safety reforms.

Ambituuni criticised the heavy reliance on military intervention. For him, the solution lies in meaningful partnerships and engagements that give communities a sense of ownership and agency over the infrastructure in their environment.

Fyneface Dumnamene Fyneface, executive director of the Youths and Environmental Advocacy Centre (YEAC), identified poverty, inadequate monitoring, and weak regulatory enforcement as key drivers of pipeline encroachment.

He also criticised the NNPC for poor risk communication, noting that the absence of consistent enforcement gives people the impression that nothing is fundamentally wrong.

“The government needs to be more aggressive and decisive in demolishing structures along pipeline rights of way. It’s not about hating the people, it’s about saving lives. Leaving such structures, no matter how temporal, increases the risk of fatalities in the event of an explosion,” Fyneface said.

*Marylyn Adebayo, a geophysicist, told TheCable that the probability of pipeline failure due to the encroachment in Abule-Ado “is very high”.

“It’s not a regular densely populated area, it’s a conurbation. If there is an explosion or fire hazard, it’ll affect a lot of people. People’s lives carry a very heavy premium, so it has to be prioritised,” Adebayo said.

“Your findings show complete negligence of safety protocols, complete negligence of administrative and engineering controls.”

She said based on her experience working with the NNPC, the problems of oil bunkering, vandalism, and encroachment will not be resolved until the Nigerian military is investigated.

“The generals are the ones giving out licenses and giving out right of way,” she claimed.

THE RISKS THAT LIE AHEAD

The NNPC said between 2001 and mid-2019, it recorded over 45,000 breaks on its downstream pipeline networks across the country.

According to NEITI, between 2017 and 2021, Nigeria lost crude oil valued at ₦4.33 trillion due to pipeline breakages, and spent another ₦ 471.49 billion on pipeline repairs and maintenance during the period.

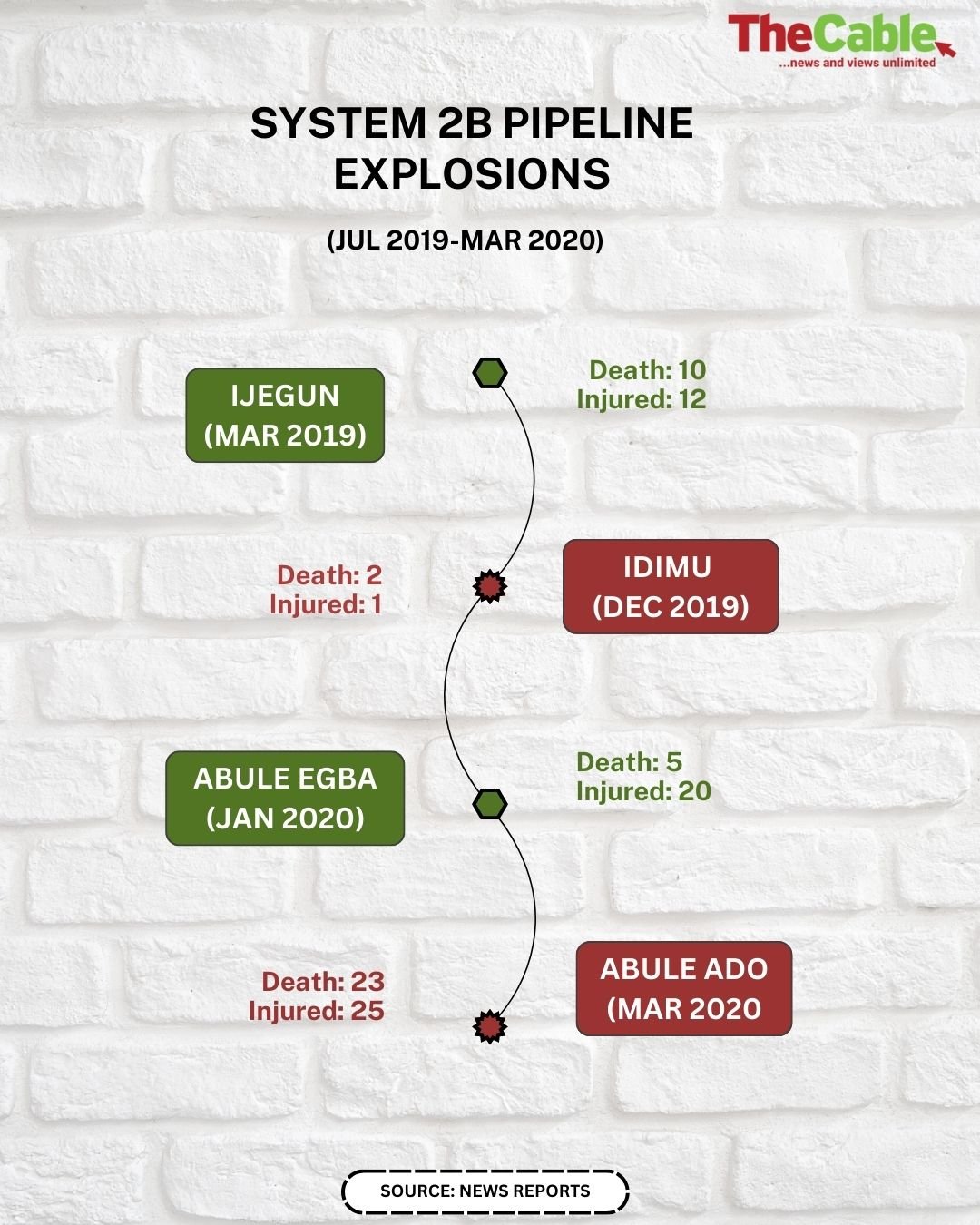

Within eight months before the Abule-Ado incident, three other explosions were recorded at Ijegun (July 2019), Idimu (December 2019), and Abule Egba (January 2020) — all along the System 2B. These incidents claimed at least 40 lives.

Fyneface told TheCable that over 1,000 lives have been lost to pipeline explosions in the Niger Delta.

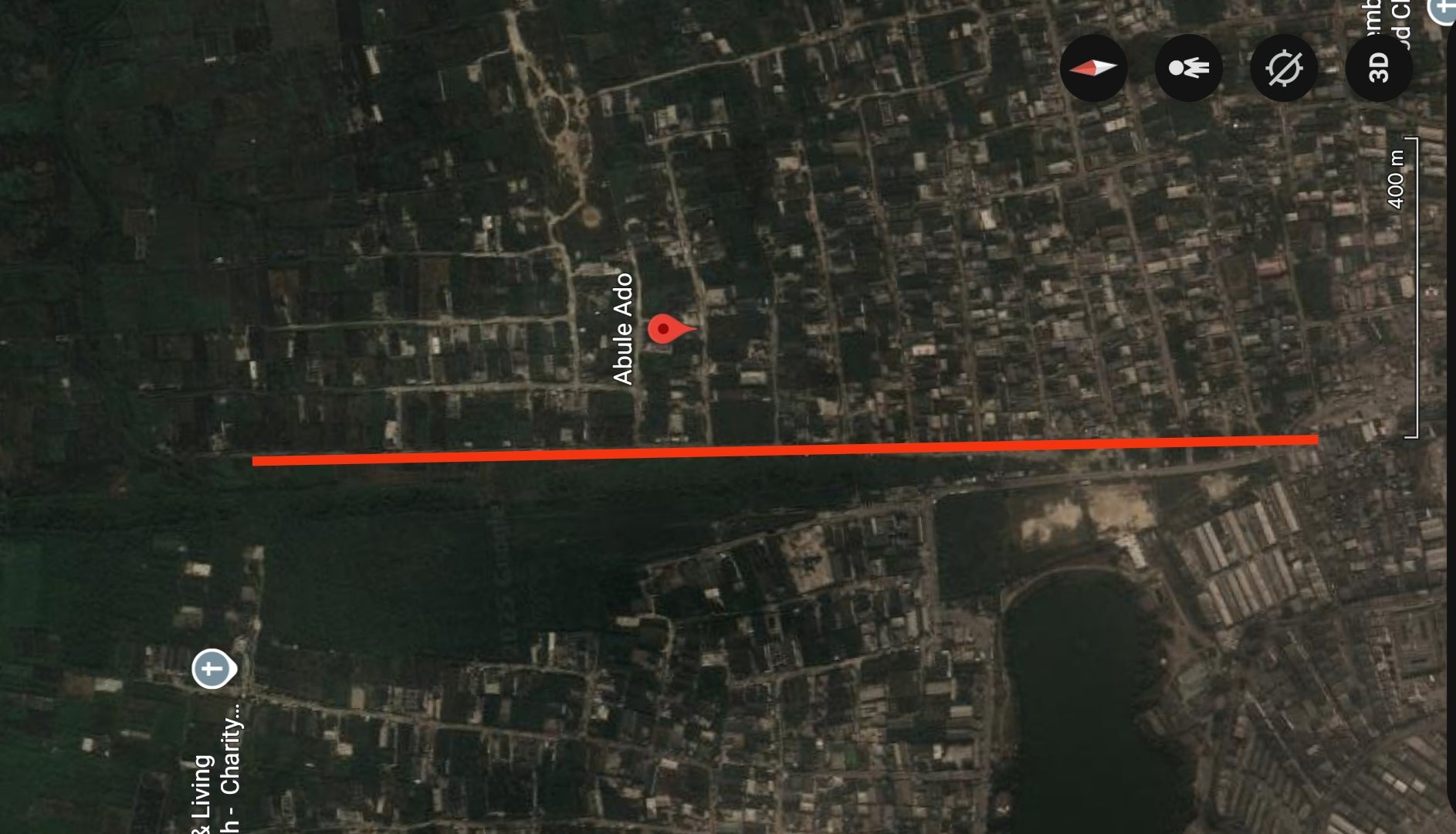

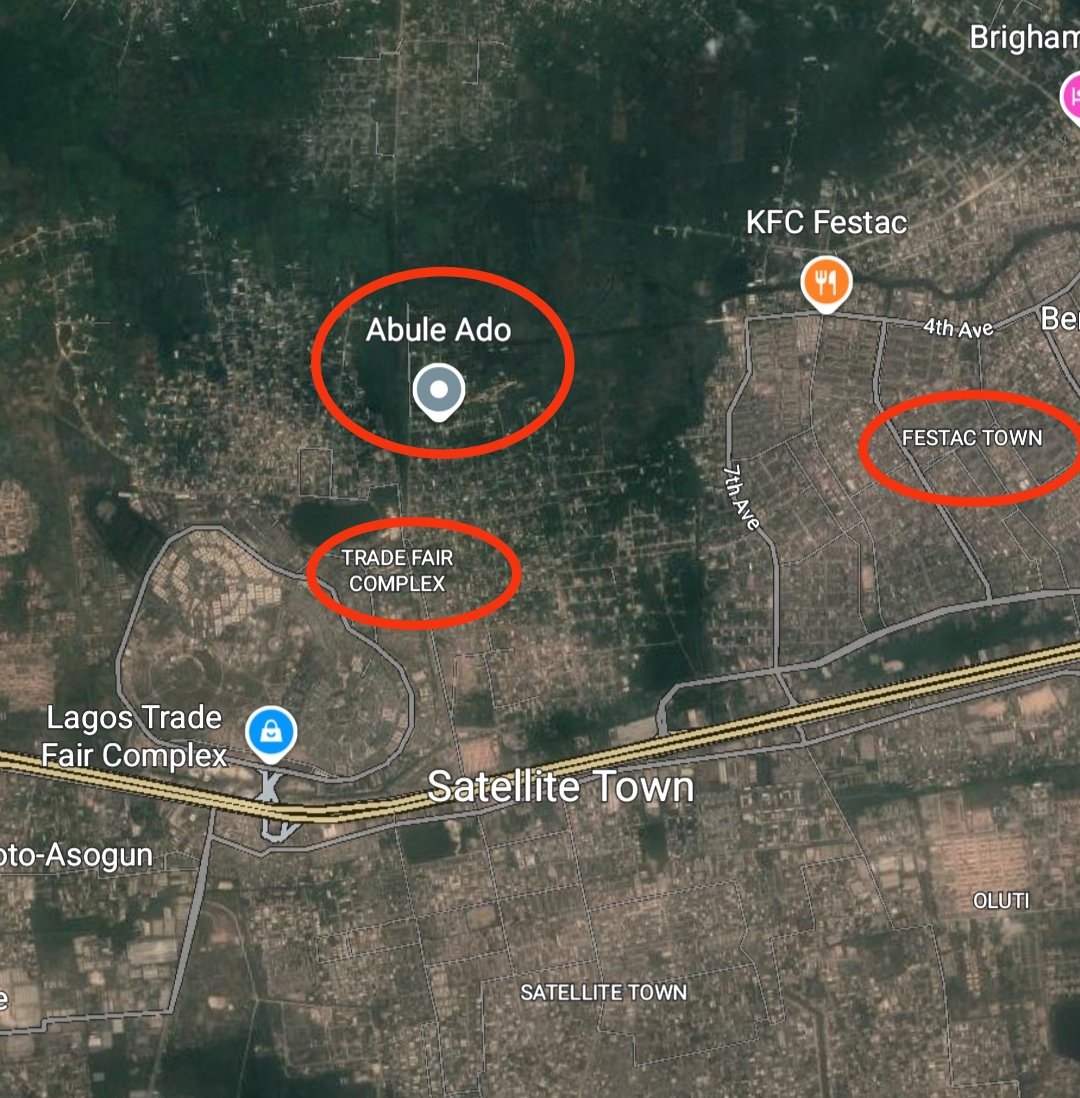

Abule-Ado lies between the Lagos International Trade Fair Complex — a sprawling 322-hectare commercial hub along the Lagos-Badagry Expressway — and Festac Town, a federal housing estate named after FESTAC ’77, the iconic month-long festival that celebrated African music and arts, which drew visitors from around the world.

Its strategic location has made the community highly sought-after, driving a surge in housing and population growth. On any given day, hundreds of residents, students, and business owners move through the community. With a high-pressure pipeline running beneath such a densely populated area, coupled with poor regulatory oversight, Ambituuni warns it is “only a matter of time before another disaster happens”.

Community members said the NNPC neither engaged them before nor after the blast regarding the safety of residents’ lives and properties.

“So, we’re still at their mercy,” Akinduro said, fearful of what the future holds.

Editor’s Note: Names marked with an asterisk (*) are pseudonyms used to protect the identities of the individuals concerned.

This report was facilitated by the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under its Report Women! Female Reporters Leadership Programme (FRLP) Fellowship, with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.