Aerial view of gold mining activities in Zamfara state

BY LAMI SADIQ

Nigeria loses over $9 billion annually to illegal mining, with a substantial portion tied to the gold sector. This investigation reveals how a significant share of gold extracted from the north-west is funnelled into terrorism financing.

In Zamfara’s gold-rich underworld, Kachalla Mati, successor to slain bandit kingpin Halilu Sububu, reportedly rakes in ₦300 million weekly from illicit mining fields. The gold is smuggled across borders, where it either generates cash to procure weapons or is directly bartered for firearms, intensifying instability across northern Nigeria.

Thirty-five years ago, Hussaini Isah scraped alluvial gold from the earth of Dan-kamfani, in north-west Nigeria, without looking over his shoulder. Today, he digs deep underground, hunted by fear and surrounded by violence and destruction that have engulfed many parts of Zamfara state.

Advertisement

Back in those days, they camped in forests, worked till dawn, and lived off gold mining. “It was a hard job, but it provided our daily living,” he said. That life has now been disrupted, as armed bandits terrorise gold-rich communities in the north-west and parts of north-central Nigeria, killing locals and forcing artisanal miners such as Isah into near-slavery.

For years, Nigeria’s north-west region has faced persistent insecurity, driven by bandits who exploit weak governance and porous borders. Initially fuelled by farmer-herder conflicts, these groups have evolved into organised criminal networks heavily reliant on cattle rustling, kidnapping for ransom, robbery and extortion to sustain their operations. However, since 2022, the artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) sector has turned into a key source of financing, fuelling large-scale violence and instability and stimulating a demand for firearms and ammunition.

While the Nigerian government has deployed the military to disrupt their activities, bandits often regroup, raze villages, displace hundreds of thousands of people and defy authority. The scale of the violence, as revealed in a joint report by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime (GI-TOC) and ACLED, found that between 2018 and 2023, banditry deaths in Zamfara and Kaduna states reached above 4,758, surpassing fatalities fuelled by violent extremist groups in the country’s north-east region.

Advertisement

Gold, a portable and untraceable source of wealth, offers bandits influence and control. As economic and political instability shakes governments worldwide, the global demand for it as a haven surged to a staggering 4,606.2 metric tons in 2024. In regions like Nigeria, where formal mining oversight is weak, this creates an avenue for bandits to become major players in the sector.

Constitutionally, the federal government has exclusive control over solid minerals, even though the sector contributes less than 1% to the national GDP. However, revenue has seen a positive rise, with a 16% increase from ₦345.40 billion ($226 million) in 2022 to ₦401.87 billion ($263 million) in 2023, the highest in a decade, according to an audit report by the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI). Yet, experts warn this represents only a fraction of its true potential, as illegal mining continues to bleed government resources.

To formalise the sector and track the flow of Nigeria’s gold, Dele Alake, the minister of solid minerals development, announced in July that over 3000 artisanal cooperatives had been registered. Alongside this effort, the Presidential Artisanal Gold Mining Initiative (PAGMI) was launched in 2019, aiming to buy gold from artisanal miners under the National Purchase Programme to ensure revenue is remitted to the government. But for Isah and many artisanal miners across Anka and Maru in Zamfara, as well as Birnin Gwari in Kaduna, bandit control over mining communities has made these initiatives impenetrable, leaving huge deposits of gold in the control of non-state actors.

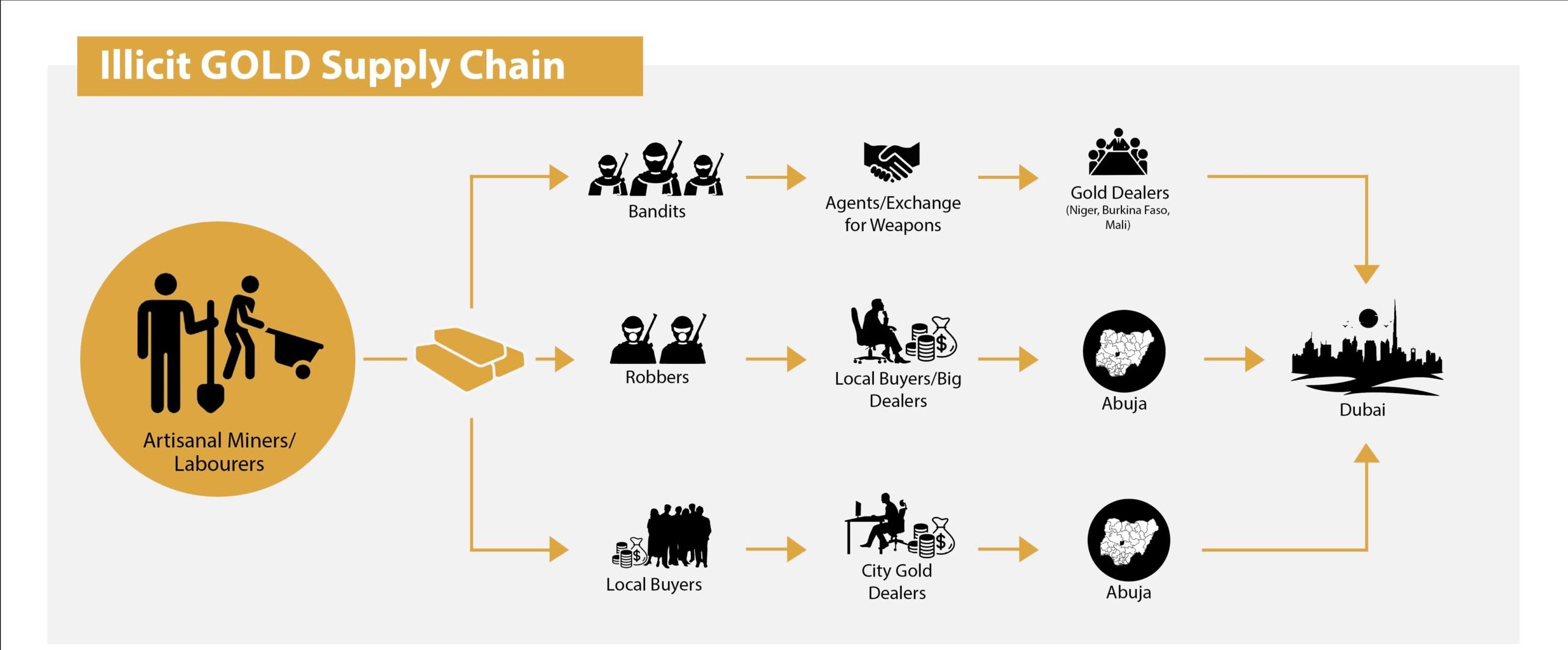

In this investigation, bandit leader, Kachalla Mati, said to be the successor of slain bandit kingpin, Halilu Sububu, boasted of extracting gold worth ₦300 million (US$196,000) weekly. A large part of it is either exchanged for weapons or sold in black markets within the Sahel, and the proceeds are used to procure firearms. The gold eventually ends up in Dubai, the United Arab Emirates, which has become the world’s second-largest gold trading hub, and a go-to selling point for Nigeria’s illicit gold. These illicit transactions increase bandits’ influence and access to firearms that spread and sustain instability in northern Nigeria.

Advertisement

EXPORTED RICHES, VANISHED GOLD

Before 2022, there was little evidence to link armed bandits to the gold mining sector because the intense labour made their involvement unlikely. Moreover, banditry had thrived on cattle rustling, kidnapping for ransom, and community levies. But as mass displacements and military action slashed those revenues, bandits turned to artisanal gold mining, taking over major sites and forcing locals to work under their control.

To speak with gold miners, I travelled to Birnin Gwari, in Kaduna state, where the immediate past governor, Nasiru el-Rufai, once boasted had more gold than South Africa. Incidentally, it is also the epicentre of Kaduna’s banditry.

Journeying through the 126-kilometre stretch Kaduna-Birnin Gwari highway was laced with anxiety. Not long ago, it was considered one of northern Nigeria’s deadliest routes because it was bandit-infested. However, a peace pact between bandits and government authorities in early 2025 made the road “relatively safe”. Despite this assurance, uncertainty often engulfs road users, especially since peace pacts with bandits have not always been sustainable.

Advertisement

A few minutes into the often-desolate Kaduna-Birnin Gwari Road that stretches into vast, ungoverned territories, the scale of Nigeria’s prolonged insecurity and widespread displacement was strikingly evident. Haunting traces of abandoned farming communities, such as Unguwar Yako, Tsohuwar Udawa, and Manini, loomed quietly overgrown by shrubs that offer a sobering reminder of the lives that once lived there. Residents had been forced to relocate as a result of constant attacks and abductions by armed bandits.

Due to the pothole-ridden road and limited or non-existent telecommunication services, the journey from Kaduna to Birnin Gwari extends twice as long as the typical one-and-a-half-hour drive. Yet, after three hours, we arrived in the town of Birnin Gwari, a place that has remarkably resisted bandit attacks.

Advertisement

To meet with artisanal gold miners, I, in the company of local vigilante men, who help fortify the community, travelled the 16km bumpy, untarred road to the Bugai mining site. Buzzing with activity, in a wide pit, mud-covered youths were seen working in sync. Shovels in hand, they dug and heaved soil to the edges. Nearby, others washed and processed the freshly dug gold-bearing earth.

“It is our right to mine. This is how we hustle, especially since what we are doing is not illegal,” said Mohammed Bello, a senior artisanal miner. But Nigeria’s Minerals and Mining Act, 2007, which provides requirements for mining, categorises Bello and many of his colleagues as illegal miners since they have no registration with the government.

Advertisement

Bandits had visited that mining site less than 10 months before this interview in May, said Jafar Ibrahim, another miner. He recalled their ultimatum: “Hand over the gold or be killed. We complied, surrendering ₦2 million ($1,300) worth of gold,” he said. But he acknowledged that bandits’ provocation had declined since the peace pact with the government.

Over 300 kilometres from Birnin Gwari, artisanal gold miners in Maru and Anka of Zamfara state equally depend on the informal sector to survive. For three decades, Isah worked across mining fields in Anka, finding just enough gold to cater for his family. Now working under bandit-controlled fields, he said the gold is dug in large quantities, and the quality appears good.

Advertisement

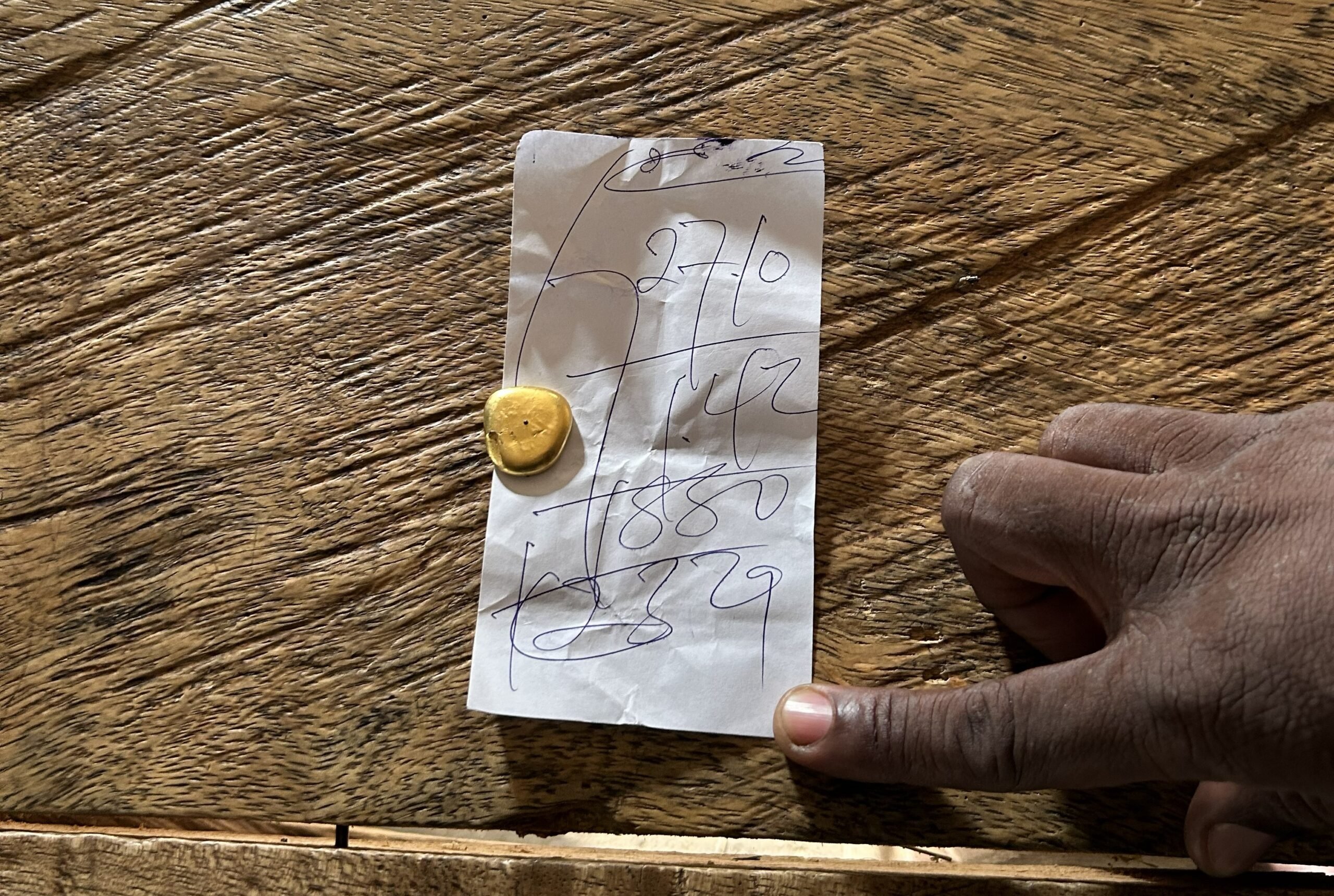

While gold dealers praise Anka’s gold, they claim it is second in purity to that of Maru, where purity could reach 23 karats and, occasionally, 24k, its purest form. For a smooth business transaction, locals use three measuring units for excavated gold: Per cent, digo and gram. Digo is a Hausa term that loosely translates to a drop. Gold dealers explained that 10 per cent makes up a digo, while ten digo make up one gram of gold.

And so, local dealers often have to pile up gold in little quantities to reach a substantial gram before they move it to bigger selling points, such as the Pollo Market in Gusau, Zamfara state. From there, the gold makes its journey to Abuja and to Dubai. Aliyu Adamu Almajiri, spokesperson for Zamfara’s Gold Buyers and Sellers’ Cooperative, confirmed that gold from the market travels to Dubai and weekly transactions in the market are about ₦250 million (US$164,000), a sharp drop from before the insecurity.

But gold dealers are not the only ones eyeing Dubai. From underground mines, bandit-controlled gold finds its way to global black markets, fuelling a far-reaching terror economy.

Explaining their role, bandit leader Kachalla Mati said gold from his controlled mining fields in Anka is stockpiled for weeks, then smuggled through the Nigeria/Niger border into the Sahel. Through this route, the gold indirectly makes its way to Dubai.

Although less prominent than Sububu, Mati is said to command scattered mining camps in Dan-kamfani, Kawaye, and Duhuwa, operating across the Bagega and Wuya wards of Zamfara’s Anka.

In one of two recorded interviews through an intermediary for this investigation, the bandit leader revealed that he extracts between 40 to 50 solos daily from a single mining site. A solo is a heap of gold-layered sand filled in cement bags. At the first scheduled interview conducted in Hausa, Mati, who was nursing a gunshot wound to the leg, ignored a question about how he sustained the injury but said overall, he makes between ₦200-₦300million ($130,000- $196,000) from gold mining weekly. He, however, added that a huge part of the gold is sold outside Nigeria.

Pressed for the specific countries, Mati got irritated: “It is not your business where we sell our gold. You want to alert the security agents, right?” After he calmed down, he boasted: “If we want to, we sometimes sell it here (Zamfara). We send our boys, and sometimes people from the city bring the money to us; sometimes, we send it to Dubai.”

Though he did not clarify how the gold journeys from Nigeria to Dubai, SWISSAID’s 2024 report, On the trail of African gold, shows that a large chunk of Nigeria’s undeclared gold, especially from the ASGM sector, is smuggled out and directly or indirectly ends up in the UAE. The report reveals a wide gap between Nigeria’s declared and non-declared gold production from ASGM, with declared production gauged at 1.96 tonnes in 2022 and non-declared estimated at between 14.3 and 15.6 tonnes per year in the early 2020s. It further explained that undeclared gold from Nigeria reaches the UAE directly through the airports, while smuggled gold, like that of Mati, makes its way to Dubai through Niger, Togo and Mali.

Many studies align with this argument, especially since Bamako, Mali’s capital, serves as a major regional hub offering favourable export terms for illicit gold mined around the Sahel, for smuggling to the UAE. Mali hosts around 140 gold comptoirs or gold trading posts, even though most operate outside formal registration, making it a key gateway for laundering gold into the UAE and into the global supply chain.

The Nigerian government acknowledges this problem and, in 2023, pushed for joint regulations with the UAE to curb illegal trade and boost mutual economic gains.

‘WE DIG, ARMED BANDITS GAIN’

Across Zamfara and Kaduna states, artisanal miners share a common story: bandits first appeared as curious observers, then gradually seized control of mining fields and forced locals to work. While bandits generally avoid physical labour, Isah said they take control of fields and treat miners like slaves. “They beat us and sometimes shoot to kill,” he said and described working in week-long shifts, with each day yielding heaps of gold-layered sand.

The situation is the same in Maru, where Kabiru Dahiru said some bandits give out entry tickets to miners on shifts. He described the ticket as a piece of paper with the name of the bandit leader written on it. “It provides protection for us against abduction by other bandits. When they see it, they know we are going to work for another bandit, and they let us pass,” he said.

But not all bandits are local. Miners often overhear bandit leaders introduce partners from Niger and Burkina Faso who leave mining sites with as many solos as their motorcycles can carry. “If we mine 10 solos, they might spare one to share among 10 of us,” Isah said. “But often, their boys could intercept us and seize it.”

Bandits’ interference in the gold mining sector forced artisanal miners to change locations, but often, they see no change in bandit tactics. Jafar Ibrahim, a native of Tsafe in Zamfara, fled to Birnin Gwari, while Ibrahim Lawal and many artisanal miners fled Maganda village of Birnin Gwari, but said that in many areas where gold abounds, bandits have a grip on the area.

Lawal, who is the chairman of artisanal miners in Maganda, said in some instances, bandits wait for them to dig, wash, and process, then seize the gold. “Sometimes they ambush us on the road and then move the gold to Farin Ruwa or Nachibi, where they refine it,” he said.

Having fled Maganda, Lawal and many of his colleagues now dig for scrapes through the rocky terrain of Rima, 10 km away from Birnin Gwari town.

But beyond preying on artisanal miners, Ashiru Usman, the chairman of artisanal gold miners in Birnin Gwari, explained that gold-rich communities of Maganda, Layin Mai Gwari, Janruwa, Tsohuwar Garin Birnin Gwari, Farin Ruwa, Naccibi, and Saulawa have all been overrun by bandits.

“Bandits have made these high-yield sites inaccessible,” he said. “Many miners have now relocated closer to Birnin Gwari town for safety.”

HOW BANDITS TIGHTEN CONTROL

Efforts to conduct one-on-one interviews with artisanal miners in bandit-controlled Bagega and Wuya wards in Anka were frustrated by the high risks. Therefore, five artisanal miners, including Isah, were convinced to travel to Anka town for the interview, but only three showed up.

Nonetheless, on the day of the interview, the 110-kilometre journey from Gusau to Anka was almost suspended after news made rounds that bandits had laid an ambush on the 71-kilometre Maiinchi/Anka route, a corridor that runs through Zuru in Kebbi state. Security advisers described the route as one of Zamfara’s perilous, subject to random attacks due to the existence of several cattle routes frequented by bandits.

It was a Wednesday morning in May, and tension rose sharply after the Kwanan Maiinci Y-turn, which veers travellers off the Gusau–Sokoto Road towards the isolated Maiinchi-Anka road. The desolation offered little reassurance, and for a while, the vehicle went into silence. Every second weighed heavily on the heart, save for the sight of seven scattered checkpoints, manned by armed community vigilante groups.

Roughly 26 kilometres to Anka, a police post became visible, and later, a military checkpoint followed, then finally, a full military formation, which residents said helps fortify the town against bandit infiltration.

Anka town has, in the last eight years, provided refuge for thousands of displaced persons, from nearby villages of Duhuwa, Kawaye, Zakkuwa in Bagega ward, as well as Dan-kamfani, Dorowe, Jakkuka and Kurukuru in Wuya ward. To consolidate control, bandit attacks are often ruthless. Aisha Abubakar, a 35-year-old housewife, recalled how the attack on Dorowe forced out over 3,000 displaced persons who are now taking refuge at the Anka emir’s palace IDP camp.

“They killed about 26 people that day,” she recalled, saying the dead included two of her brothers, four nephews and four brothers-in-law. It was the same for Rahama Abubakar and Fatima Garba, residents of Kurukuru and Jakkuka villages, who fled their communities alongside hundreds of residents. For those who dared to return, the consequences are often fatal, said Rahama, who recounted a recent killing of seven villagers who returned to assess their maize farms.

Reinforcing the complexity of the situation, the women doubted that the attacks on their communities were linked to the rich deposits of gold buried beneath the earth.

“Bandits took over Dan-kamfani and the mines, but the people were allowed to stay and work for them,” argued Fatima. “They let them have enough gold to buy food. If they’d asked, we’d equally have stayed willingly.” Experts align this position to cooperate with bandits in exchange for protection as a tactic employed by non-state armed groups to gain legitimacy among locals and present themselves as protectors.

But even in their perilous circumstances, the spirit of defiance persists among some residents.

As the vigilante commander in Zamfara, Rabiu Bawa knows the cost of defending such communities. “Just recently, I wanted to restructure my men, and I was very upset because many of them had been killed in a clash with bandits,” Bawa said, his voice heavy with grief.

MIDDLEMEN IN THE SHADOWS

Muhammadu Abubakar, a gold dealer in Anka, transitioned from artisanal mining to gold trading within a decade. Local dealers like Abubakar are often the first point of contact once gold is extracted and processed. “We weigh the gold and pay the miners. Sometimes, I buy between 10 to 20 grams of gold in a month,” Abubakar said, adding that other dealers may buy more.

Though there is no way of knowing if gold from bandits makes its way into their hands, Abubakar and his colleagues at the Pollo Market insist they never purchase gold from bandits. They, however, admitted that the criminal groups operate through middlemen.

Like many organised criminal networks, bandits rely on intermediaries for smooth operations. These middlemen play a vital, yet shadowy role in gold processing, transportation and sales to the movement and exchange of firearms and ammunition.

But this investigation found that the middlemen involved in the gold trade are often distinct from those operating in the arms trade, even though they are, in most cases, within the same communities and their paths may cross.

To evade detection, middlemen in the gold sector embed themselves within local communities, as explained by Isah and corroborated by other artisanal miners. He said some of them own private gold processing centres and serve as couriers of gold and cash for bandits. His account was re-echoed by Rabiu Bawa, the vigilante commander in Zamfara, who explained that when in need of cash, bandits use agents to transport gold to dealers at Gusau’s Pollo Market.

But the shadowy nature of agents is deeply entrenched in the protection they get from bandits, explained security and intelligence expert Kabiru Adamu, who said apart from protecting gold fields, bandits also protect agents to move freely between locations.

Subsequently, to protect their interests and ward off security agents and rivals, bandits require weaponry, said Adamu, managing director of Beacon Consulting, a renowned firm providing enterprise risks and security management solutions in Nigeria and the Sahel. Interactions with personnel from the Nigerian Immigration Service and Customs officers stationed at the Nigeria/Niger border reveal that trafficked weapons coming into the country are mostly tracked through Jibia, in Katsina state.

“Jibia is about 40km from Gusau, and if they can come in undetected, the weapons move to parts of Zamfara and other states, especially Kaduna and Niger states,” said an immigration officer who requested anonymity.

The role of middlemen in the sector is driven by the emergence of a war economy, much like the north-east at the height of Boko Haram’s insurgency, explained Sani Kukasheka Usman, the consultant director of Corporate Affairs and Information Services (DCAIS) at the Nigerian Army Resource Centre (NARC), Abuja, who said bandits exploit societal deprivation to smuggle and transport firearms and ammunition.

“Sometimes transporters of arms are recruited consciously or unconsciously,” he said. “Take, for example, someone living in poverty. If you hand them a parcel to deliver, they might not ask questions until they’re arrested.” Usman, a former director of army public relations, said while fear forces some to act as intermediaries for bandits, others are driven by greed.

FROM GOLD TO GUNS

Increased demand for weapons among non-state actors has placed Nigeria in the 5th spot on the 2025 Global Terrorism Index, trailing behind Burkina Faso, Pakistan, Syria, Mali and Niger. The Sahel region, geographically straddling Nigeria, remains the global terrorism epicentre, accounting for over half of all global terrorism deaths. With competition over the region’s mineral resources, especially gold, contributing to ongoing instability in Mali and Burkina Faso, it not only exposes northern Nigeria to the regional patterns of insecurity but situates Nigeria among key hotspots of violence and arms trafficking, facilitating both importation and domestic production of weapons in West Africa.

No doubt, Nigeria’s porous borders, with about a thousand illegal entry and exit points stemming from Benin Republic, Chad, Niger Republic and Cameroon, remain a critical factor in arms smuggling, said General Usman.

The country’s vulnerability to global insecurity was re-echoed by Christopher Musa, the immediate-past chief of defence staff (CDS), in July, when he said Nigeria harbours 40 per cent of the over 500 million illegal small arms and light weapons circulating in West Africa. He noted that the weapons, smuggled from conflict zones in the Sahel and North Africa, have empowered terrorists, bandits and ethnic militias, escalating violence in northern Nigeria.

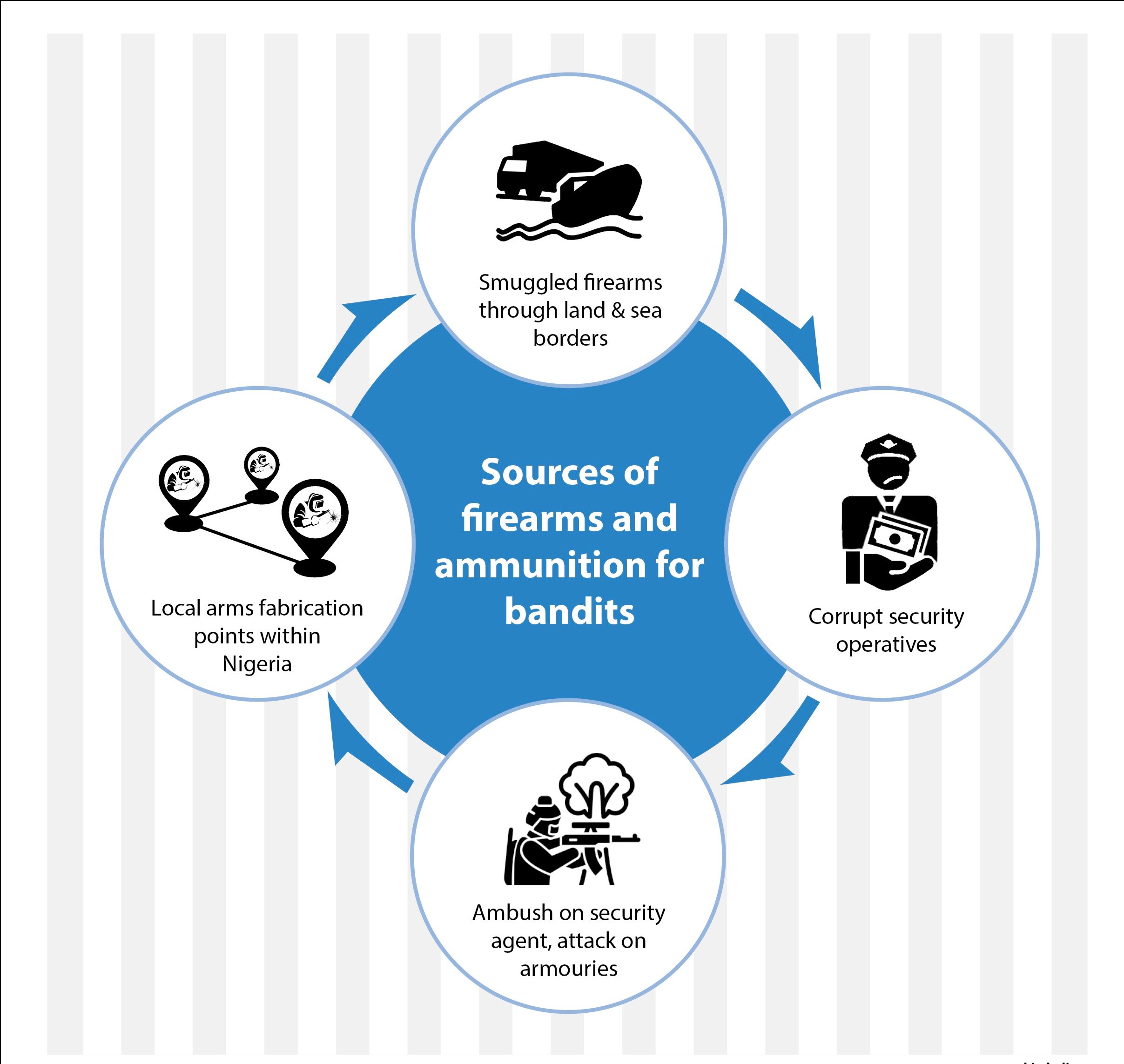

However, apart from smuggled firearms, the federal government has acknowledged that a wide range of weapons used by non-state actors, including bandits, were sold to them by corrupt security agents. Speaking on this, Adamu said that though a bulk of the weaponry is smuggled through the land and sea borders, other sources include local manufacturing points where weapons such as the AK-47 are fabricated, as well as those sold by corrupt security officials.

Shedding light on Nigeria’s local weapon manufacturing dynamics, Usman noted that the illegal sector has grown “remarkably innovative, capable of fabricating nearly every type of weapon”.

Therefore, to increase their capacity for violence, bandits rely on foreign and domestic channels for firearms, funded substantially by gold extracted from Nigeria’s informal mining operations. These weapons, Adamu explained, help bandits protect mining sites against the Nigerian authority and other rival groups as well as gain more influence and control.

One figure who embodied this nexus of illicit gold mining and arms acquisition was slain bandit leader Halilu Sububu. Before he was killed in a military ambush in September 2024, Sububu was described by Murtala Rufai, professor of history and international studies at Usmanu Danfodio University, Sokoto, as a key arms supplier to bandit groups and reportedly controlled mining sites across Zamfara, Katsina, and Kaduna. Whether Sububu funnelled gold profits into gun deals or outrightly swapped the metal for weapons remains unclear. What is certain, however, is that since his death, a new player, Kachalla Mati, has stepped in to fill the void.

Isah, who worked under mining sites controlled by Sububu and now under the control of Mati, said bandits often boast of how gold proceeds are used to purchase advanced weaponry, including Rocket-Propelled Grenades.

When questioned about these claims, Mati initially dismissed the inquiry as too sensitive. He later confirmed that proceeds from gold were used for various purchases, including weaponry. “Some firearms could even bring down a plane,” he said and added, “There are African countries where weapons are sold in shops.”

For international weapon transactions, Mati said gold, treated as a foreign currency, is stockpiled over several weeks and then smuggled across borders into Niger or Mali. There, it is sold, and the proceeds are used to buy weapons that are later trafficked back into Nigeria.

Offering a glimpse into how these transactions unfold, he said trade in weapons within Nigeria operates on a cash-based system using naira. He explained that bandits sell their gold through intermediaries in local markets to raise cash used to acquire firearms either from fellow bandits, gun runners, or local fabricators.

In one instance, Mati recounted how a gun runner from Plateau state was intercepted by security forces while transporting a weapon to his group. Without identifying the type of weapon, he reinforced how middlemen trafficking firearms and ammunition across state lines are typically motivated by upfront deposits, with the rest paid after delivery.

“We agreed to pay N1 million, and an advance of N800,000 was paid via POS (Point of Sale), but the driver was arrested,” he said.

Providing perspective into the pricing of AK47, a widely used assault rifle among Nigeria’s security forces and a favourite for non-state actors, he said new foreign versions cost between ₦5 and ₦6 million ($3,266-$3,920) while the locally fabricated versions cost around ₦500,000 ($326). Mati said bandits equally expand their arsenals from attacks on military and police armouries and ambushes on security forces, adding that such versions of AK47 are sold among bandits, between ₦500,000 to ₦1million ($326-$653), depending on their condition.

Ammunition, the bandit leader said, is typically sold in “mudu”, a metal grain measuring bowl popular in Nigeria. A mudu, according to him, costs anywhere between ₦800,000 to ₦1.1million ($522-$720), depending on type and market situation.

His insights on the price of a new foreign AK47 rifle are in line with a recent argument by Nuhu Ribadu, Nigeria’s national security adviser (NSA), who said the price of the foreign AK47 had reached N5 million in 2024, against less than N500,000 in 2023 and therefore making the rifle out of reach of bandits.

But Adamu challenged the notion that weapon prices determine their availability, arguing that bandits rely on diverse revenue streams to procure firearms. He blamed the Nigerian government for doing little to curb bandits’ access to weapons and ammunition and warned that attention must shift beyond Libya to include Sudan as a growing source of weaponry.

“Even ammunition is easily accessible to bandits, and this is evident in the way they shoot recklessly,” he said.

SWAPPING GOLD FOR GUNS

Since 2021, the Nigerian government has responded to the activities of armed banditry with a series of aggressive measures, including military interventions, a sweeping ban on mining activities and a declaration of a “no-fly zone” on Zamfara to halt what it suspected as the swap of gold for arms by bandits. Though this suspicion has lingered for years, no concrete evidence has emerged to confirm how this transaction is conducted and with whom.

Mati, however, gave a glimpse into these transactions, boasting that under Sububu, bandits exchanged gold for arms with partners from Mali and Burkina Faso. He, however, said that since he assumed leadership, he has now established links with firearm dealers from Algeria.

“What we do is to exchange the gold for weapons,” he said. “We will not give them money; we give them the gold and they give us the guns,” Mati clarified, revealing the mechanics of the barter system in which gold is exchanged directly for firearms.

Building on his earlier explanation of black-market firearm pricing, he added that the cost of each firearm is negotiated, and once agreed, gold is exchanged based on its equivalent value as payment for the weapon. Based on this explanation, with high-quality gold selling at ₦155,000 per gram at Gusau’s Pollo Market in May, it would require between 33 to 39 grams, valued at over ₦5 million to purchase a new foreign-brand AK-47 rifle. And for Mati, who boasts of raking in approximately N300m weekly from his mining operations, that is equivalent to 60 AK-47 rifles from a week’s gold production.

Explaining further, he said the Algerian partners come with their own gold measuring device, “that one that makes that ‘dit, dit’ sound,” adding that once the gold is exchanged, any outstanding balance is settled at a later transaction. During the interview, Mati claimed that the weapons are delivered in batches and in May, he said about 40 firearms had arrived from Algeria, but when asked to reveal them, he became suspicious and refused the request.

Experts agree that the connection between gold and firearms is a driving force behind banditry in Nigeria’s north-west. Adamu explained that though gold mining increases the capacity for bandits to access firearms and ammunition, bandit influence is equally derived from gaps in governance, which they exploit to take over Nigeria’s many ungoverned spaces.

We reached out to the Nigerian government through the National Counter Terrorism Centre, under the office of the National Security Adviser and the National Coordinator, AG Laka, a major general, agreed to an interview but later ignored repeated requests. Mohammed Idris Malagi, the minister of information, also did not respond to several interview requests on the findings of this investigation.

Though the Nigerian military is currently conducting an ongoing operation against bandits in the north-west, the spirit to fight for their freedom remains a burning desire among civilians.

“If not for their guns, we’d fight back,” said Ibrahim Lawal, chairman of artisanal miners in Maganda. As a resident and artisanal gold miner, Lawal understands that every ounce of gold seized by bandits increases their access to firearms and strengthens their grip on communities. “The best way to tackle this,” he said, “is for the government to cut off their access to weapons and take full control of the mining sites.”

Beneath the bloodstained earth of north-west Nigeria, sources say Mati and other bandits continue to wield power over mining fields. However, Isah has since relocated from Dan-kamfani to Giwaye, near Anka town, where he is scraping a living from the soil.

“The gold is not much here,” he said, “but it is better than slaving for bandits.”

• Names of artisanal miners used in this report have been changed to protect their identities.

This article was developed through a mentorship programme with the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime (GI-TOC) and La Cellule Norbert Zongo pour le journalisme d’investigation en Afrique de l’Ouest (CENOZO), as part of the “Support to the Mitigation of Destabilising Effects of Transnational Organised Crime (M-TOC)” project. The M-TOC project is commissioned by the German Federal Foreign Office (GFFO) and implemented by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH and GI-TOC from 2024 to 2025. This article is totally independent and does not necessarily express the views of GI-TOC, CENOZO, GIZ or GFFO.