The first part of this investigation narrates harrowing accounts of sexually abused children and the deep scars they now live with. But beyond these personal stories lies a bigger picture, one painted in stark numbers. In this second part, DevReporting’s Christiana Alabi-Akande went undercover to some police stations in Lagos to expose how security operatives extort families of victims, even at their vulnerable moments.

What the numbers say

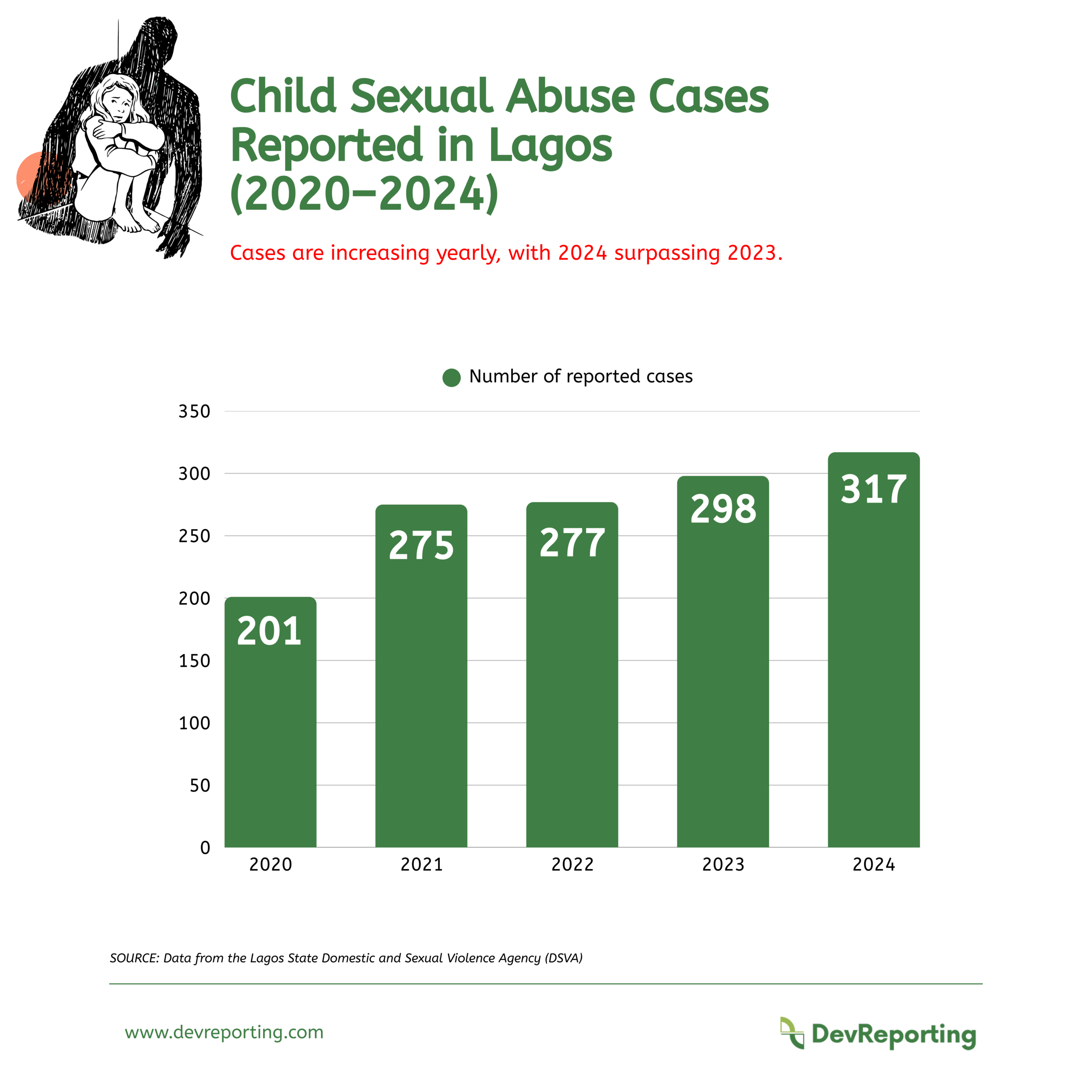

Investigations by DevReporting have revealed grim statistics of sexually abused children in Lagos, a city nicknamed Nigeria’s commercial capital and one of the largest and fastest-growing economies in Africa.

In 2020 alone, the state recorded 4,302 cases of domestic and sexual violence, according to the Domestic and Sexual Violence Response Team (DSVRT), a government agency responsible for coordinating responses to sexual molestations and child abuse in the state.

Advertisement

The data indicated that children accounted for 1,718 of those cases, including 109 cases of defilement, four cases of minor-to-minor defilement, and 88 cases of sexual harassment.

In 2021, DSVA said 3,943 cases were reported, out of which 1,222 involved children, including 172 cases of defilement, 58 cases of sexual assault by penetration, and 45 attempted rape or attempted sexual assault by penetration.

Advertisement

The agency recorded 5,929 cases in 2022, with 2,486 cases involving children, comprising 230 defilement cases, 33 sexual molestation cases, and 14 cases of defilement/sexual molestation involving minor-to-minor.

In 2023, the number of reported cases increased to 6,389, with 2,576 involving children, comprising 263 defilement cases and 35 cases of sexual molestation.

The agency’s 2024 annual report shows 6,456 reported cases in the year, with 2,531 involving children, which comprises 223 defilement cases, 93 sexual assault (molestation) cases, and a single case of defilement by a minor-to-minor.

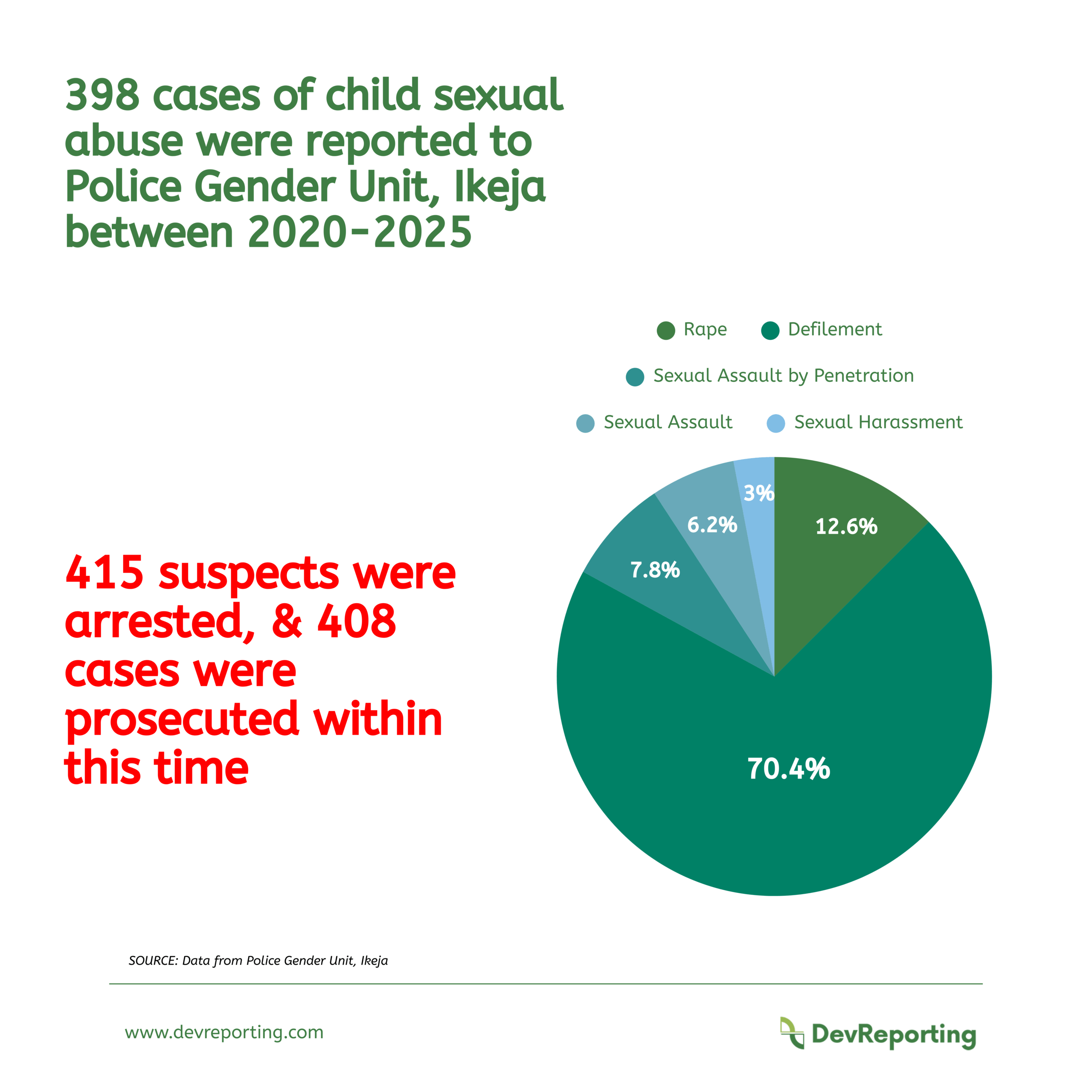

Police Gender Unit

Advertisement

Meanwhile, the Lagos state police command gender unit said 398 cases of child sexual abuse were reported to its gender unit between 2020 and 2024. These, it said, included 50 cases of rape, 280 cases of defilement, 31 cases of sexual assault by penetration, 25 cases of sexual assault, and 12 cases of sexual harassment.

In its response to DevReporting’s inquiry, the police, in a letter signed by the second officer in charge of the gender unit, Ndumfiok Emmanuel, a superintendent of police, said that though the unit might not be able to provide the specific number of convictions, 415 suspects were arrested and 408 cases were prosecuted during the period under review.

Lagos’ fight against sexual abuse

Through DSVA, Lagos is one of the few Nigerian states with a structured framework for addressing domestic and sexual violence and safeguarding child rights.

Advertisement

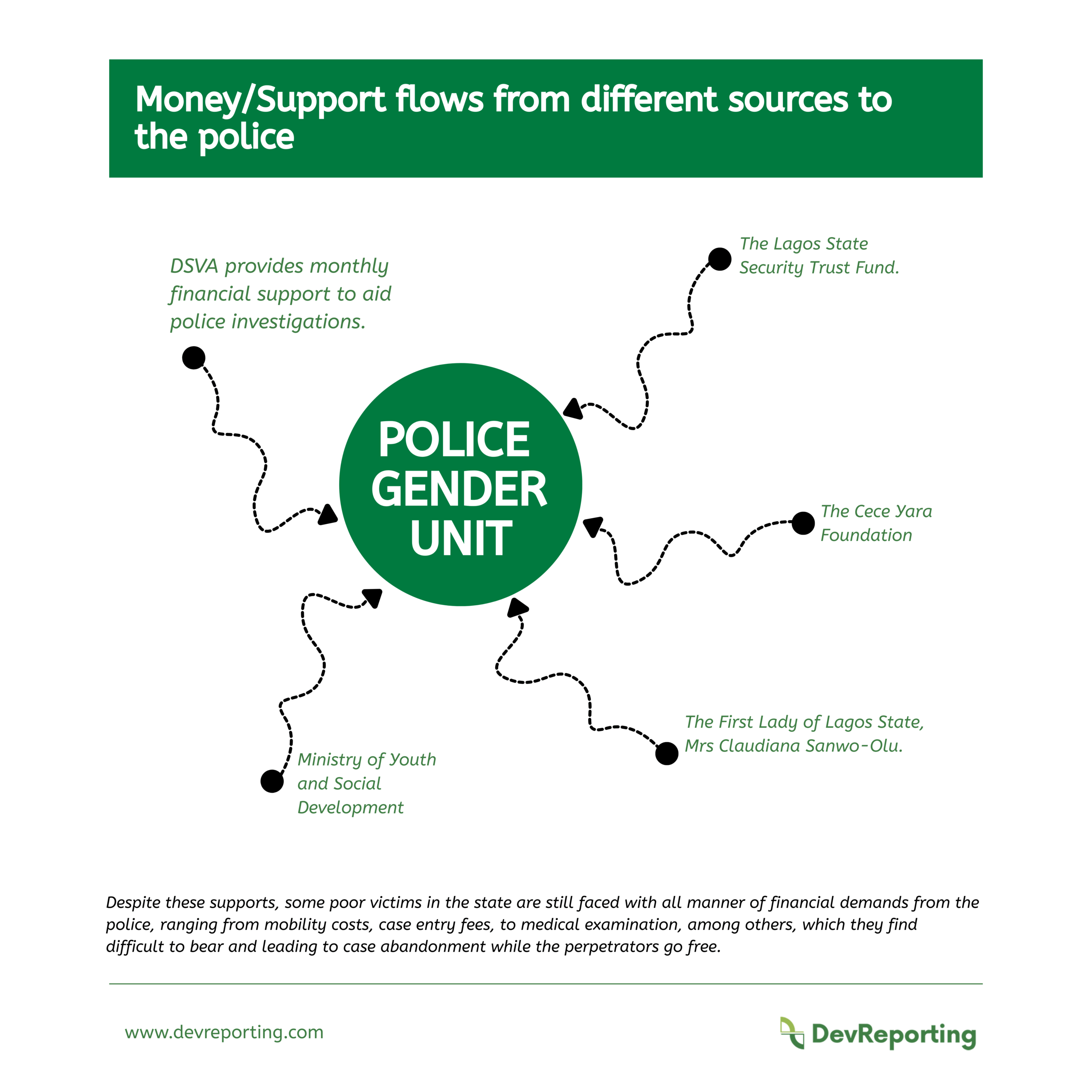

Findings by DevReporting revealed that the state provides financial support to the police gender unit, which coordinates all gender-based desks across police divisions in the state.

It was gathered that 21 family support units (FSUs) operate across different police divisions, handling cases of domestic violence, sexual assault, child abuse, and other family-related issues. In divisions without FSUs, such cases are managed by the Juvenile, Women and Children (JWC) unit or the Human Rights unit.

Advertisement

The police stations with FSU are located in Adeniji Adele, Ajah, Ajegunle, Alakuko, Badagry, FESTAC Town, Ikotun, Igando, Ikeja, Ilupeju, Ipaja, Ikorodu-Igbogbo, Ikorodu-Imota, Ikorodu-Owutu, Okokomaiko, Bariga, Epe, Isokoko, Surulere, Ilasan-Lekki, and Ketu.

DSVA said it offers financial assistance to police gender units. Its executive secretary, Titilola Vivour-Adeniyi, a lawyer, told DevReporting that because the police play a critical role in ensuring that perpetrators are held accountable and sometimes serve as the first point of call for survivors, the agency provides monthly financial support to aid police investigations and ensure that cases are swiftly charged to court.

Advertisement

She said: “We have a good working relationship with the police. Aside from building their capacity to ensure they are exposed to best practices for investigating cases, we provide them with financial support monthly to support investigations and ensure that cases are charged to court swiftly.”

Vivour-Adeniyi did not state the specific amount being given to the police monthly.

Advertisement

Similarly, the officer in charge of the police gender unit, Ikeja, Toyin Kazeem, an assistant commissioner of police (ACP), who confirmed that the unit receives support from DSVA, also failed to disclose the specific amount.

The unit also noted that within the last five years it has received support from the office of the Lagos state first lady, Claudiana Sanwo-Olu; the Cece Yara Foundation, Ministry of Youth and Social Development (MYSD), and the Lagos State Security Trust Fund.

According to the unit, survivors/victims are referred to medical facilities where medical services are free for all survivors of SGBV cases in the state, such as police medical facilities, Mirabel Centre, Women at Risk International Foundation (WARIF) and Idera Sexual Assault Referal Centre, among others.

Kazeem, the unit boss, however said the support offered the unit may not necessarily mean money, citing the MYSD, which she said has been supportive in the area of allowing the unit access to its external shelter, especially for child survivors.

She also mentioned that the unit got a van donation from the Police Trust Fund to aid logistics

Where is accountability?

A schedule of budget estimates and actual expenditures from 2020 to 2024 obtained from the office of the accountant-general of Lagos state shows a rise in funding for the DSVA, particularly in overhead and capital allocations.

In 2020, N8 million allocated to the unit was fully spent on overheads, with no capital expenditure recorded, as DSVA had not yet become a full-fledged agency. The same amount was recorded for 2021.

But from 2022, following its establishment as an independent agency, the budget allocations surged. That year, N627.4 million was estimated for overhead costs, with an actual expenditure of N480.8 million. Capital expenditure was estimated at N100 million, with N73.3 million spent.

In 2023, the overhead estimate stood at N559.3 million with N504.3 million spent, while capital expenditure stood at N6.34 million with N6.32 million spent.

The 2024 estimate for overhead was N473.5 million, with an actual of N472.8 million, and capital was N47,385,851 with an actual of N29,623,540.

Despite these significant allocations, DevReporting’s request for breakdown of specific line items and expenditure by the agency was not provided by the agency. This made it impossible to verify how much of these funds were directed towards supporting survivors of sexual violence or what is channelled as financial support to the police gender units.

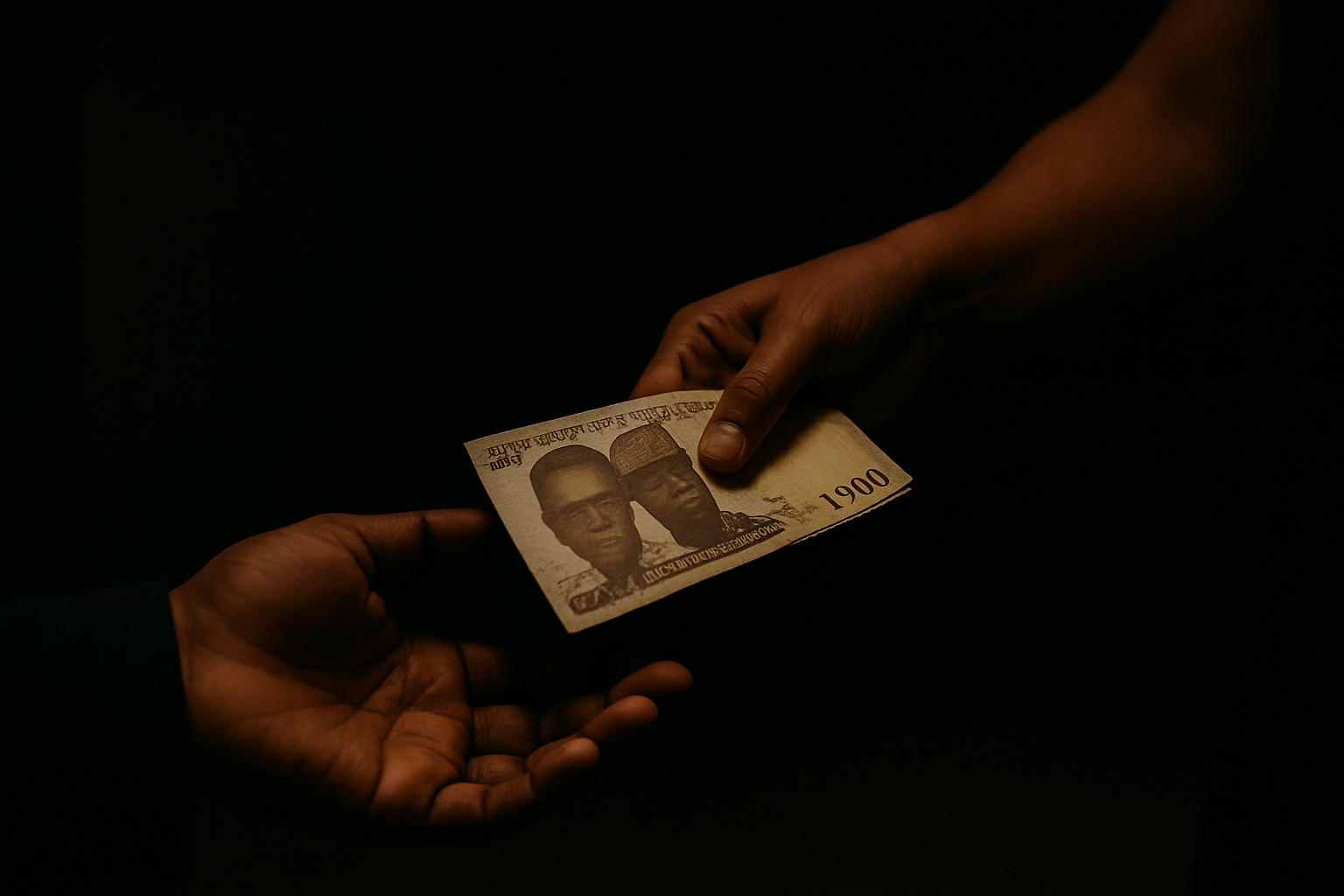

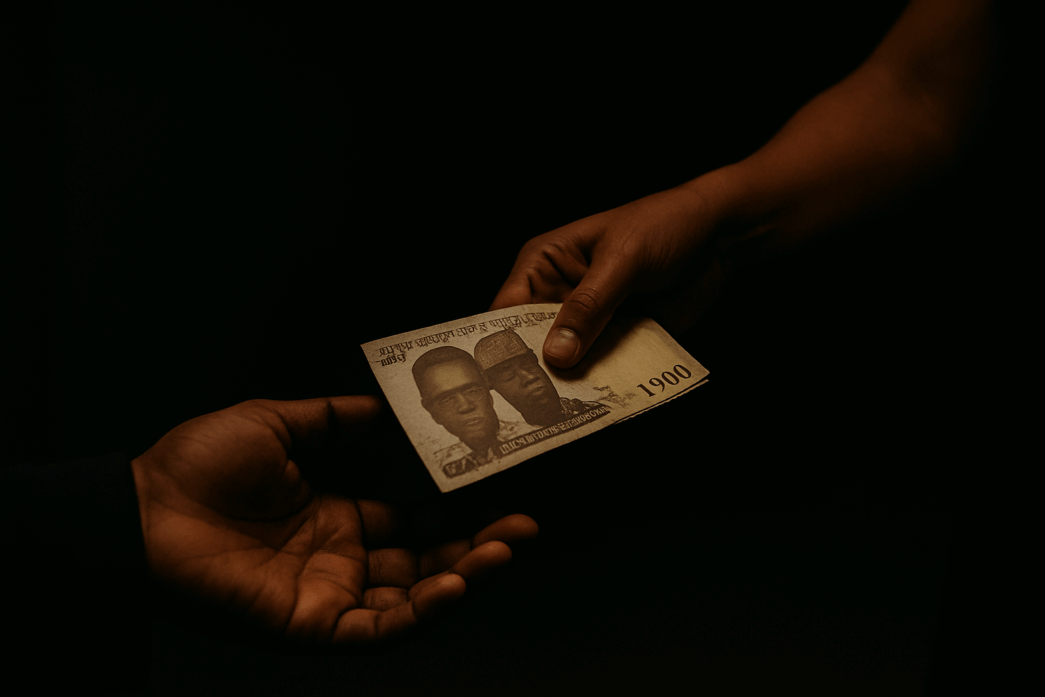

Despite streams of support, extortion persists at police stations

At about 11:30 a.m. on 10 July, this reporter, accompanied by a mother and child, visited Gowon Estate police station, located along Ipaja Road in Alimosho local government area of Lagos, posing as people willing to profile the case of a four-year-old girl who a young man in the neighbourhood defiled.

At the station, they were directed to the juvenile, women, and children (JWC) unit, where a policewoman, identified simply as Officer Oyin, requested the details of the incident. She said a formal statement should be made.

The child’s mother pretended to be distraught. She was harshly scolded by the officer, who accused her of carelessness and blamed her for the supposed sexual violation of the child.

The female officer also briefly interrogated the child and a statement was taken. However, she said since the Divisional Police Officer (DPO) and the officer in charge of the juvenile unit were unavailable to properly handle the case, she listed some of the requirements to pursue the case to include payment of N5,000 for case entry, and payment for transportation of officers to the scene of the crime.

The complainants pleaded with the officer to reduce the cost, explaining that they were not aware any payment was required. Officer Oyin eventually collected N1,000 and gave them a medical form to be taken to Aregbesola Medical Health Centre, Egbeda, a public health centre located within the Alimosho local government area.

Officer Oyin further said, “After visiting the scene of the crime, we will refer this matter to the Gender Unit at the state command in Ikeja and then, you will have to bring money for chartering a vehicle to move everyone connected to the case, including police from the division to the Gender Unit in Ikeja.

“Then, all documentation already done at Gowon Estate Police Station will be replicated at Ikeja. You should also be ready to mobilise for another visit to the scene of the crime, this time, for the team from the Gender Unit.”

Meanwhile, at the health centre, an unidentified official who attended to this reporter said the test is free but that the family of the victim would purchase gloves for the use of the healthcare workers to conduct the test.

Like Gowon, like Elere

Similarly, on 21 July, this reporter visited Elere police station, Agege local government area of the state, where she pretended to be a good Samaritan seeking justice for a 10-year-old sexually abused maid.

Also, the officer in charge of the station’s juvenile unit was not on seat, and efforts to reach her on the phone were to no avail as she did not pick the calls to her phone. The policewoman at the station, who said she could not give the exact amount it would cost to mobilise the police to pursue the case since her boss was not around, demanded N50,000 to cover “case entry” for the brief statement made by the reporter, and “other logistics necessary for the arrest of the alleged perpetrator.”

“We will go with a male police officer in case the perpetrator proves stubborn. We’ll also have to give the officer something. But if you don’t have up to ₦50,000, you can tell us what you can afford,” said the policewoman, simply identified as Bose.

Isokoko police station stands out

Also in Agege, the situation was different at Isokoko police station. The reporter had reported that a three-year-old daughter of her friend’s younger sister was defiled by a young man in their compound.

The policewoman, identified simply as Rebecca, was furious and committed to taking action. She, however, requested a referral from either DSVA or an NGO as a precondition to taking action.

“If we see the referral letter, we will first need to see the mother of the child and the child for interrogation. What it will cost you is not much; the difficult area is going to court. You will open a file, and after the investigation, we will duplicate the file and send it to the Directorate of Public Prosecution (DPP) for legal advice, then you will go to court. It’s only that area that can cost you some money, in the form of financial support,” the policewoman, Ms Rebecca, said.

Isheri-Oshun police station

Also, on 21 July, the reporter visited Isheri-Osun police station in Alimosho local government area, where a policewoman, identified simply as Pepe, requested to see the victim.

“You will come with the complainant so that I will follow him to go and make an arrest, and if you want us to transfer the case to our headquarters, we will, but you will charter a vehicle that will take us there, you will pay to open a file, and you will see me big time,” she said.

Stakeholders speak

Commenting on the development, the chief executive officer of Harmony Advocacy Network, Harmony Tachie, said many sexually abused children and their parents are silenced not just by trauma but also by poverty, as they are faced with the inability to afford medical examinations or legal representation.

She added that the fear of stigma or retaliation from perpetrators who are often known to the victims, combined with a general lack of awareness about their rights, further complicates the pursuit of justice.

“For these parents, the trauma doesn’t end with the violation. It deepens with every naira spent trying to report the case. From the first visit to a police station to the countless trips between hospitals, lawyers’ offices, and courts, the financial toll of seeking justice can rival the emotional one. In some instances, the police ask for money just to ‘open a file’, a practice that leaves the poor behind,” Tachie said.

The founder of DOHS Cares Foundation, a non-profit organisation that works towards freeing women, children, and vulnerable people from violence, abuse, and exploitation, Ololade Ajayi, said justice is often unattainable for indigent survivors because cases are quashed at the police station before reaching court.

Ajayi said: “Police will ask for money if you want to pursue a rape case, except for the few officers who are conscious of the gravity of the offence. Imagine asking an indigent family to pay N20,000 or N50,000 just to fuel a car for an arrest. In a recent case in Ikorodu-Owutu, a policeman asked a groundnut seller to bring N20,000 before addressing her complaint.

“When I accompanied a lecturer to report her case, the IPO asked her to pay N50,000 before even listening, having known that she is a lecturer. The policewoman classified her based on her job and demanded money, supposedly to call and pick up the perpetrator.”

Such practices, according to Ajayi, undermine justice and compel many survivors to settle privately, often under threat or inducement. “Violence against women and girls should not be treated as a private matter. It is a public issue requiring strong support systems. Too often, family or community pressure silences survivors,” she stressed.

Roadblocks to justice

Vivour-Adeniyi of DSVA confirmed that some individuals have had distressing encounters with certain law enforcement officers, due to blame game, victimisation, or demands for money before the case could be investigated.

While she hinted that several factors hinder the swift delivery of justice, she noted that the agency is working to build the capacity of the police.

According to her, major factors hindering the swift delivery of justice for sexually abused children include a lack of information as to what to do immediately after a child has been sexually abused. She said parents or guardians should not bathe a child who has been sexually abused, so as not to destroy evidence.

Vivour-Adeniyi said: “There is also a lack of information as to where to go. Some people go to a pharmacy to complain and get drugs, while some go to hospitals that are not designated to attend to sexual assault issues. Closely linked to that is the need to ensure that the case is reported to the police swiftly.”

She also spoke about the length of time it takes to prosecute cases, noting that the huge number of cases and lack of many special courts for such offences also make access to justice a difficult process.

“Our mandate is to coordinate response, provide services, ensure referrals are made promptly so that the survivor, post-trauma, can access all the critical support they need,” DSVA boss added.

Expert speaks on trauma of child sexual abuse

A psychiatrist and psychotherapist at the University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, Abiola Tajudeen, a professor, described the impact of sexual abuse on children as deeply traumatic, noting that it leaves both physical and psychological scars that can last a lifetime.

He explained that beyond the physical violation, which may involve injuries such as vaginal tears or, in rare cases, Vesico-Vaginal Fistula (VVF), the mental and emotional scars are often far more enduring.

He added: “Sexual abuse is never by consent. It is a forceful violation of a child’s body and person. Even in cases where the child seems unaware of what happened at the time, the memory often resurfaces as they grow older, and it begins to shape how they see themselves and the world.”

Tajudeen further noted that many victims carry deep emotional burdens such as guilt, shame, and confusion, which he noted may lead to mental health challenges such as depression, anxiety, and in severe cases, suicidal thoughts or psychotic episodes. He added that some victims may turn to drugs or alcohol to numb the pain.

“Over time, such unresolved trauma can affect a person’s identity and personality, as some develop personality disorders. Others engage in self-destructive behaviour or become anti-social, lashing out at others in anger or even joining criminal gangs to reclaim power,” he said.

NGOs offer lifeline

In the vacuum created by what experts describe as a failing justice system, non-governmental organisations have become the last hope for many survivors.

From providing legal aid and trauma counselling to covering transportation and hospital costs, these groups step in where the state steps back.

But then, the reach of the NGOs is limited, as they lament being overwhelmed by the growing number of cases and shrinking donor funds.

Ajayi of DOHS Cares Foundation said the government must prioritise funding for gender desks, provide shelter and holistic support for survivors, and allocate resources to civil society organisations working to end violence.

Sexual assault referral centres such as Mirabel, WARIF, CeCe Yara, and Idera also provide free medical, psychosocial, and referral services to survivors of rape and sexual assault.

According to the centre manager at Mirabel, Joy Shokoya, anyone who has experienced one form of sexual abuse or the other is qualified to visit the centre. “We receive survivors from police, schools, government agencies, and religious organisations. We also receive survivors from partner NGOs.”

She said that survivors of rape or sexual assault do not need to go to the police first, saying medical and support services can be their initial point of contact. This, she said, is crucial because treatments like emergency contraception and post-exposure prophylaxis are time-sensitive and must be administered within 72 hours.

As a way forward, Tachie recommended institutionalising free medical and legal support for survivors, training police and judicial officers to handle defilement cases with sensitivity, establishing a survivor fund for indigent families, and enforcing laws against police corruption and negligence more strictly.

Until then, she said, “the poor will continue to suffer twice, first from abuse, then from a justice system that doesn’t see them.”

This report was supported by the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism (WSCIJ) under its Report Women! Female Reporters Leadership

Programme (FRLP).