A battery breaker in Lagos, Nigeria, uses a machete to hack open the plastic casing of a car battery. (CREDIT: Grace Ekpu for The Examination)

The residents who tested positive for lead poisoning live between 100 and 500 metres from True Metals Nigeria Limited and Everest Metal Nigeria Ltd, two of the most prominent companies engaged in Used Lead-Acid Batteries (ULABs) in Ogijo.

BY OLADEINDE OLAWOYIN AND FOLASHADE OGUNRINDE

The lead found in the blood of residents and in the soil of Ewu Oloye, Ipetoro, and Ewu Eruku communities in Ogijo, a border town in Ogun State, pointed to a clear source: the cluster of battery-recycling factories that powers Ogijo’s small economy while slowly poisoning the people and their environment.

Residents who tested positive for lead poisoning live within 100 to 500 metres of True Metals Nigeria Limited and Everest Metal Nigeria Ltd, two of the most prominent Used Lead-Acid Batteries (ULAB) recyclers in Ogijo.

Advertisement

True Metal Nigeria Limited is a metal recycling facility located at Km-16, Ikorodu-Sagamu Road, Ogijo, Ogun State. According to its website, the company specialises in the export of non-ferrous metals, including lead alloys, lead ingots, and copper products.

True Metals is one of Nigeria’s leading exporters of lead products. In 2022, the company shipped recycled lead to Spain, South Korea, and India. Between 2023 and May 2025, it also exported recycled lead to the United States, according to multiple trade records reviewed by The Examination and PREMIUM TIMES.

Records show that between 2022 and 2024, several companies received recycled lead from True Metals, including Trafigura Trading LLC, C. Steinweg Baltimore Inc., Wilebat SL, Hankook Bicheol Co. Ltd., and Montorretas SA.

Advertisement

Further analysis of two separate trade record sources found that, from April 2023 to December 2024, True Metals Nigeria Ltd. made at least 29 shipments of recycled lead to Trafigura, destined for the United States.

According to a 2020 report by UNICEF and Pure Earth, the global demand for lead has surged in recent decades, driven largely by the rapid growth of vehicle ownership in low- and middle-income countries. Lead prices doubled between 2005 and 2019, while the number of new vehicles sold in these countries more than tripled between 2000 and 2018.

Global Dynamics

In the auto industry, recycled lead is extensively used in automotive batteries, forming the core of new batteries through a recycling system. The lead from spent batteries is recovered, refined, and returned to the supply chain to create new ones, with recycled materialsmaking up over 80 per cent of new car batteries in the US. Experts claim that the approach conserves resources, reduces the need for mining, and makes lead-acid batteries one of the most recycled products.

While the United States and Europe recycle more than 95 per cent of their used lead-acid batteries under strict environmental controls, many low- and middle-income countries lack comparable regulations and enforcement. As a result, countless batteries are processed in informal and unregulated settings.

Advertisement

“These informal recycling operations are often in backyards, where unprotected workers break open batteries with hand tools and remove the lead plates that are smelted in open-air pits that spread lead-laden fumes and particulate. It is estimated that in Africa alone, more than 1.2 million tonnes of used lead-acid batteries enter the recycling economy each year, and much of that goes to informal operators,” the 2020 report stated.

Africa alone generates an estimated 1.2 million tonnes of used lead-acid batteries each year, much of which ends up in informal recycling operations that serve as a primary source of income for many poor households.

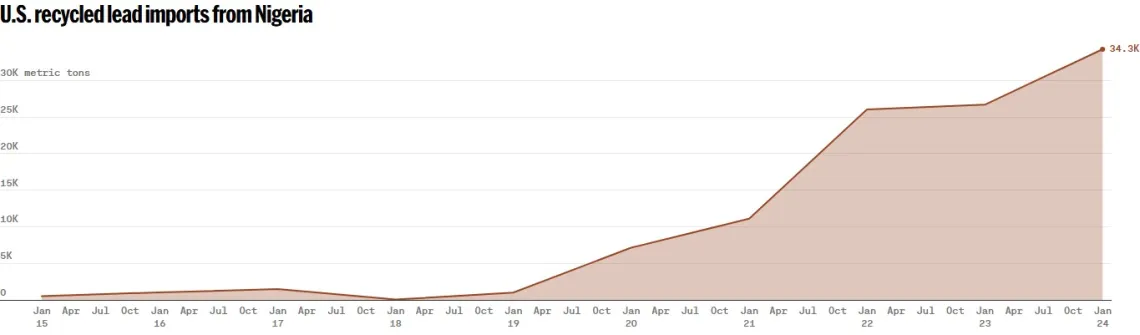

According to United Nations data, Nigeria led Africa in recycled lead exports between 2019 and 2023. The same data show that the United States imported the largest net weight of recycled lead from Nigeria during this period.

US Census records indicate that imports from Nigeria increased from under 1,000 tonnes in 2019 to 34,300 tonnes in 2020.

Advertisement

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, “USA Trade Online,”

Advertisement

Workers’ Recount Ordeals

True Metals said it aims to be “a well-organised, fully upgraded, mechanical and efficient plant that sustains development to business through class value-added products,” and by being “Eco-friendly”.

However, multiple residents and workers within the organisation told PREMIUM TIMES that the company’s promises to be eco-friendly only exist on paper, as the indiscriminate discharge of lead waste into the soil, air, and water of Ogijo falls short of international safety standards.

Advertisement

Workers report handling batteries with their bare hands, smashing them with axes, wearing torn gloves, and handling molten lead with minimal protection, while fumes drift freely into the air.

Video evidence obtained by PREMIUM TIMES showed that factory floors are cracked and cluttered, slag piles sit exposed to wind and rain, and rainwater and battery effluents flow untreated into the surroundings. Lead dust left out in the open spreads into nearby homes, classrooms, and gardens.

Advertisement

In one small-scale farm that shares a fence with True Metals, PREMIUM TIMES reporters observed blackened leaves, a sign of prolonged exposure to dust and fumes drifting from the recycling plant. The surfaces of houses and rooftops have been blackened over the years from the lead dust emitted by the company.

Every step of the operation flagrantly violates international safety standards and the National Environmental (Battery Control) Regulations 2024, exposing both workers and communities to toxic lead.

“Nobody ensures that workers have protective gear; if anything happens to you, you are on your own,” a True Metals worker, who sought anonymity for fear of victimisation, told PREMIUM TIMES. Section 49 of the National Environmental (Battery Control) Regulations 2024 states that workers handling used batteries must wear appropriate Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) as prescribed in the regulations.

Speaking to PREMIUM TIMES in the first week of November, a worker at True Metals, who asked not to be named for fear of reprisals, had just finished his shift. His face looked worn, the long hours clearly taking a toll on him. The harsh working conditions have aged him, he said, but his need to earn an honest living, even at the risk of his health, keeps him there.

(CREDIT: Source)

As the late-afternoon sun fell on his face, he recalled the many accidents he had witnessed over the years, incidents that had cost some of his colleagues an eye, an arm, and even a life.

Just like his colleagues, this worker tested high for lead poisoning.

“I am worried, I am not okay with the result,” he said, in response to PREMIUM TIMES’ enquiry on how he felt about the test result. “But how can I find a solution?” he asked aloud, confusion and helplessness written on his face.

“It is to quit the job,” he quipped, amid hesitation, adding that “I am just managing for now because I don’t have any other one yet.”

Many Nigerians struggle with unemployment. Figures from the National Bureau of Statistics indicate that the country’s unemployment rate stood at 4.3 per cent in the second quarter of 2024, approximately two years after the methodology was revised and the rate adjusted from 33 per cent.

The worker reported experiencing itching and internal heat. When a blood test was conducted by True Metals in 2023, he alleged that the results were not provided to them. The company informed them that they were fine, and it was the only test he had been subjected to since joining the company nearly a decade ago, in clear contravention of existing laws and regulations.

According to Section 48(j) of the National Environmental (Battery Control) Regulations 2024, battery recycling plants are expected to “carry out blood lead test on the facility workers at least twice every year.”

The blood and soil test commissioned by The Examination and partners and prepared by the Sustainable Research and Action for Environmental Development (STRADev) documented cases of headaches, stomach pain, anaemia, fatigue, and seizures among affected individuals.

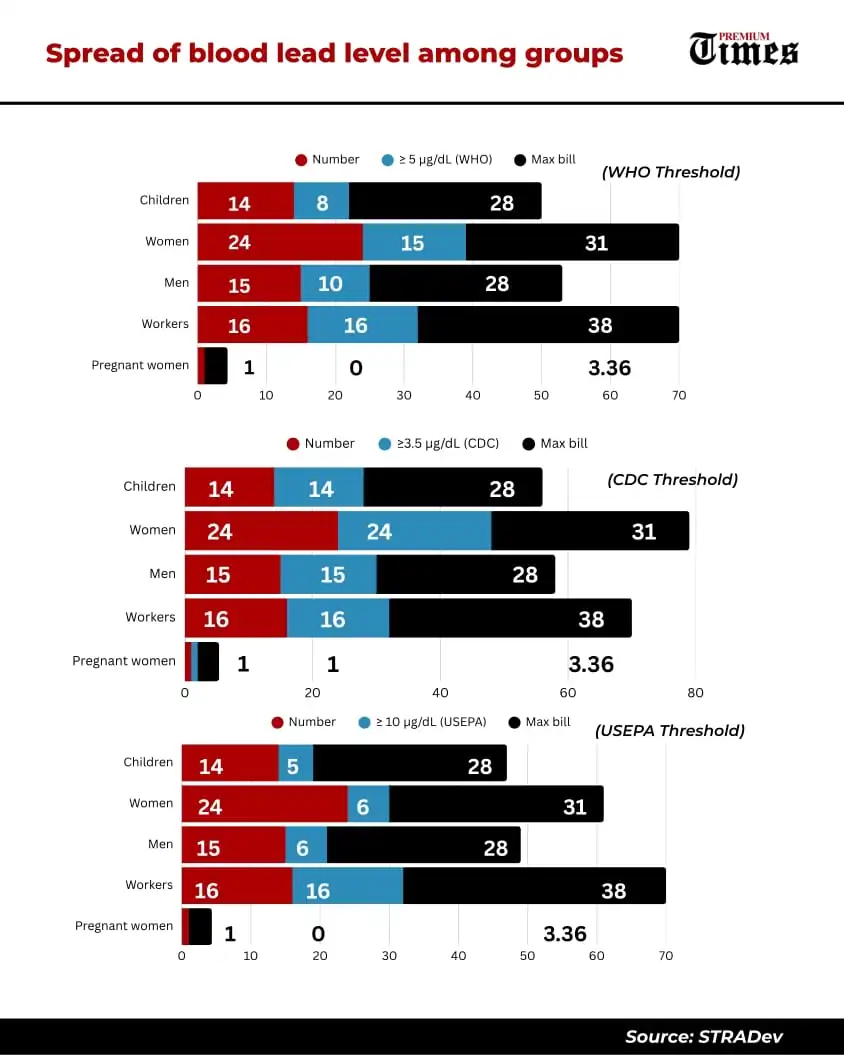

Apart from True Metals, workers and residents living near other recycling plants in Ogijo—notably Everest Metal Nigeria Ltd and African Non-Ferrous Industries Ltd—were also tested. Results showed that all 16 workers tested from the three recycling companies have lead poisoning. Their BLL ranged from 10 to 38.1234 µg/Dl. The workers held roles such as cleaning, sorting, smelting, storekeeping, and battery transportation.

The situation is not any different at Everest Metal Nigeria Ltd. The company is situated on the premises of a former iron rolling plant and has been engaged in the recycling of used lead-acid batteries (ULABs) for approximately five years.

Among the workers tested, Steven (Not real name*), a furnace operator, recorded a blood-lead level of 21.7 microgrammes per decilitre, more than five times the World Health Organisation’s safety limit.

“I feel bad. I didn’t even know that I have this level of lead inside my system. I would have left this work a long time ago,” Mr Steven said when he received his result.

For three years, he worked at the plant. Each day, he and his co-workers feed used batteries into red-hot furnaces that burn for hours, releasing thick fumes that sting the eyes and throat. They mix the acid and molten lead by hand, often without adequate protection.

“We get gloves once a week,” he said. “But the acid burns through them, and sometimes I buy new ones with my own money.”

Mr Steven said his body had started sending warnings.

“Two weeks ago, I began to feel sharp pains in my chest. Sometimes my eyes hurt, like dust is inside them. Other times, I can’t see clearly. Before I eat at night, my stomach hurts. Even when I try to urinate, I feel pain all over,” he said.

When he coughs, the sputum that comes out is black, the same colour as the smoke that rises from the furnace. Mr Steven said inspectors from government agencies visit only to take photographs or collect “settlements” before leaving.

“They don’t ask how we feel. If anything happens, you’re on your own,” he said.

Last year, one of his friends died after suffering severe swelling, symptoms that doctors linked to chemical poisoning. The company paid the family N1.5 million in compensation, he told PREMIUM TIMES.

“He stopped eating, and his body started swelling. His family rushed him to the hospital, but he died the same day. It was the chemicals that killed him,” Mr Steven said.

“Lodging”

At Everest Metal, used lead-acid batteries are collected, broken, and fed into furnaces. Workers refer to the production area as “the lodging.” There are four such lodgings, each operating its own furnace.

The process begins with the arrival of old batteries, already cracked open to remove the plastic casings. The metal and residue are mixed with chemicals and loaded into the furnace, where they are heated for four to five hours.

When the molten mixture cools, it solidifies into crude lead. The lead is then transferred to the refinery section, where it is purified and prepared for export. Throughout the process, workers are exposed to heat, fumes, and acid residue, often without adequate protective gear.

The traditional ruler of Ogijo, Oba Kazeem Gbadamosi, stated that his community has spent years advocating for battery recycling companies to operate safely.

He said that despite workshops and repeated engagements, many factories continue to operate as they did years ago, with dangerous consequences. According to him, past tests revealed “a great amount of lead… in the blood, on the ground, and in the environment where these factories are located.”

He recalled reports of severe health problems among residents, including birth deformities, persistent cough, miscarriages and even a cluster of sudden deaths of five workers within a single week.

“Some have been reported, some have not been reported, but they can be attributed to the issue of lead being emitted in the community,” he said.

He stressed that residents were not calling for the factories to shut down, but rather for them to stop polluting, adding that local leaders had worked with NGOs and the National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA) for six years to pressure operators to adopt safer practices.

Regulatory Provisions

In August 2024, the Federal Government of Nigeria unveiled the National Environmental (Battery Control) Regulations 2024 to prevent and minimise pollution and waste emanating from batteries in Nigeria. This is based on the National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA) Act, 2007, a Nigerian law that established the National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency to protect and develop the environment.

Speaking at the time, Nigeria’s Minister of Environment, Balarabe Lawal, stated that the document was part of the government’s efforts to promote the practice of battery waste disposal in an internationally standardised manner and facilitate an enabling environment for deploying renewable energy projects.

“Batteries contain hazardous materials such as lead, mercury, cadmium, and lithium, amongst others. When improperly disposed of, these materials can lead to severe health conditions, including cancer, kidney damage and neurological disorders,” he said.

In essence, the regulations aim to ensure the environmentally sound management of all types of batteries throughout their life cycle, encompassing production, use, collection, transportation, storage, recycling, and disposal. This will not only encourage best practices among recyclers but also ensure that the people and their environments are safe.

However, for workers and residents who have endured years of relentless pollution from the battery lead recycling companies in Ogijo, their realities mirror cases of regulatory failures. They told PREMIUM TIMES that they can no longer bear the toll it has taken on their health and daily lives.

In 2018, a BusinessDay report revealed that companies recycling lead-acid batteries were contaminating air, soil, and water sources in Ogun and Lagos states, resulting in high lead levels in the blood of workers and residents. Seven years later, the situation has only worsened.

Omoh Ifalanki, an executive of the Ikeoluwa Community Development Area (CDA), told PREMIUM TIMES that every attempt to stop the toxic emissions over the years has been unsuccessful. He said letters to government agencies, including the Ogun State Ministry of Environment, have gone unanswered.

A resident of Ogijo for over two decades, Mr Ifalanki explained that community members, most of whom are poor, often pool their own money to submit formal complaints about the pollution from the lead-recycling factories.

“These companies pay tax, so the government knows them well,” he said, alleging that corruption has allowed the violations to continue unchecked.

Light at the end of the tunnel?

On 17 September, NESREA announced that it had sealed nine recycling facilities in Ogijo, including True Metals, for environmental pollution.

In a statement on its website, NESREA’s Director-General, Innocent Barikor, said the “improper disposal of hazardous slag from battery recycling threatens environmental degradation and public health risks from toxic lead content. Tests have revealed the presence of lead in residents, resulting in illnesses and deaths.”

According to NESREA, the facilities were shut down for violating the National Environmental (Battery Control) Regulations, 2024. Offences cited include operating without the required environmental documents, lacking a fume treatment system, discharging black oil, failing to conduct blood-lead tests on workers, poor slag management, manual battery breaking, and non-compliance with the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) programme.

But before the announcement, The Examination, PREMIUM TIMES, and partners had conducted an independent scientific study to measure lead levels in Ogijo’s soil and in the blood of 70 workers and residents. The results were relayed to NESREA for official reaction.

The results were alarming. Of the 70 people tested, 50 had Blood Lead Levels (BLLs) above 5 µg/dL, the World Health Organisation’s threshold for lead poisoning. Every worker sampled, 14 in total, tested positive, including one employee at Everest Metal whose BLL reached 38 µg/dL, a level associated with severe neurological and organ damage.

Children and women also showed widespread exposure. Eight of the 14 children tested had BLLs above the five µg/dL benchmark, while 15 of the 24 women sampled exceeded the same threshold. One woman recorded an exceptionally high BLL of 31.06 µg/d.

These violations mirror what residents working in the facilities have long reported.

Meanwhile, NESREA had received a copy of the soil and blood test result commissioned by The Examination and prepared by STRADev before it sealed the recycling companies.

But while speaking to The New York Times/The Examination in an interview, the NESREA DG, Mr Barikor, claimed that the STRADev report was “additional information” and NESREA had done its own report “over a period of time.”

Multiple residents and workers in recycling plants in Ogijo expressed doubts about such a “coincidence”, but were delighted that action was being taken anyway. Many of them told PREMIUM TIMES that the draft blood and soil report NESREA received between late August and early September seems to have finally spurred the agency into action in Ogijo, steps it should have taken earlier.

Yet, despite the seal orders, True Metals and Everest Metal resumed operations within weeks, reopening as though nothing had happened. When asked why the companies reopened, Mr Barikor said a meeting held in Abuja between the agency and the battery lead recycling companies prompted the re-opening of the facilities. He said part of the issues discussed were the technological challenges the companies struggle with, and a protocol to be implemented within a time frame.

“The first thing we are going to do is to now collectively ensure that the legacy slags are removed. The first open action that will be cited by the public community will be the removal of the slag. That cannot take place until there is an identification of a dump site that is certified by the government. We need to work with the state to do that,” he said.

He further stated that some companies have begun to “take measures” to address this protocol on how to deal with their environmental concerns.

For workers who are put in harm’s way because the government failed to implement the safety laws and for Ogijo residents whose health slowly ebbs away, the assurances mean little.

In multiple interviews with PREMIUM TIMES in the first week of November, workers who sought anonymity for fear of victimisation said after production resumed at the factories, nothing really changed.

“After shutting down for two weeks, we came back to work, but they gave only a few of us boots. I buy my safety boots to protect myself,” a resident who works for Everest Metal said. Workers at True Metals shared similar experiences.

In an interview with The New York Times and The Examination, Chris Pruitt, executive chairman of the board of East Penn Manufacturing, a major US battery maker with ties to Nigerian companies, stated that “under five per cent” of the lead came from Nigeria. After receiving questions from The Examination and partner newsrooms, Mr Pruitt said, East Penn stopped buying lead from Nigeria and began to tighten its supplier code of conduct.

Lead-recycling companies speak

The Examination and PREMIUM TIMES wrote to True Metals and Everest Metals. We sought to know what information Hankook, its South Korean trading partner, and Trafigura, a US-based trader that purchases recycled lead from Nigerian recycling companies, requested from True Metals about pollution controls, worker safety, and environmental practices before purchasing its recycled lead.

We also asked True Metals to respond to inspection findings, reports of unsafe dust levels, allegations of weak safety practices, community pollution complaints, sourcing practices from informal collectors, and evidence of soil and blood contamination, among other issues.

The two companies did not respond to letters seeking clarification on the matter.

We also contacted BPL Nigeria Ltd., one of the companies assessed in the 2024 ProBaMet project, with questions about its safety practices. We asked what information Trafigura requested from BPL regarding pollution controls and worker protection, and whether BPL agreed with the ProBaMet findings that described “severe weaknesses,” significant emissions, and unsafe exposure to lead.

The 2024 ProBaMet project was a multi-level intervention led by six NGOs, among them STRADev, in partnership with the German Cooperation. On the government side, the effort brought together NESREA, the Ogun State Environmental Protection Agency (OGEPA), and other regulatory agencies.

We also requested clarification on specific inspection observations, including the lack of controlled acid collection, poor dust handling, and a large dust heap located near the furnace.

Additionally, we inquired whether BPL disputed NESREA’s September 2024 allegations that the company had violated the new Battery Recycling Regulation in areas such as the absence of environmental documents, unsafe manual breaking, improper slag management, and failure to conduct worker blood-lead tests.

In its response, BPL did not address our specific questions but instead issued a broad statement about its role in Nigeria’s evolving recycling industry. The company stated that it collaborates with international partners, including Trafigura, to meet environmental and safety requirements and is implementing a 17-point improvement plan that encompasses monitoring, worker safety, infrastructure, and responsible sourcing.

BPL added that it is committed to aligning with the 2024 Battery Recycling Regulation and continues to engage regulators and partners to raise operational standards.

Meanwhile, it neither confirmed nor disputed the specific inspection findings that contained NESREA’s allegations.

African Non-Ferrous, another recycling company, said it recognises the environmental and health risks associated with lead recycling and has been working with Nigerian authorities to address compliance issues under the 2024 battery recycling regulations.

The company stated that it has implemented improvements in environmental monitoring, worker safety, infrastructure, and responsible battery sourcing to align with Nigerian and international standards. It added that it remains committed to collaborating with regulators, customers, and community stakeholders to enhance environmental performance while maintaining jobs in the sector.

An email enquiry sent to the Ogun State Environmental Protection Agency (OGEPA), the agency responsible for enforcing relevant environmental standards, regulations, and laws, elicited no response as of press time. Efforts to also reach the agency through multiple telephone calls placed to a number listed on its website proved abortive.

What next for Ogijo residents, workers?

After the blood test was conducted, there was a brief medical consultation with the affected residents and workers, while sachets of ferrous sulfate, an iron supplement used to prevent or treat anaemia, were provided.

Many of them were advised to relocate from their communities, with no clarity on compensation or chelation therapy for those with extremely high blood-lead levels, as recommended by the WHO.

Whether the ferrous sulfate will help remove the lead remains uncertain, as a 2020 UNICEF and Pure Earth report notes that once lead settles in the body, there is no real cure, and much of the damage from long-term exposure is irreversible.

Nasir Tsafe, a member of the rapid response team for lead poisoning in Zamfara State and coordinator of the Centre for Lead Poisoning Control and Prevention at King Fahd Abdul Aziz Children and Women Hospital, told The Examination, PREMIUM TIMES and partners that exposure above 3.5 micrograms per deciliter is dangerous.

“According to the CDC, this could start to show some effects in the body, especially cognitive effects on children who are less than five,” he explained.

Mr Tsafe stressed the need to stop ongoing exposure, noting that children can ingest lead through contaminated clothes and materials brought home from smelting sites. He said smelters need proper training and hygiene practices, including removing contaminated materials, bathing with soap, and changing into clean clothes before returning home.

“Any ordinary soap will remove 99 per cent of the lead. Then they must put on clean clothes that are completely not used during the smelting… so that when they go home, they have less exposure to give to their children.”

He, however, said government action on lead poisoning has been deprioritised.

“Right now, the government has put down lead poisoning aside. It’s no longer their priority… It’s still a time bomb. It’s going to come back. It’s still going to come back to be killing more and more children,” he said.

This is the second part of this two-part investigation. You can read the first part here.

This investigation is reported in partnership with The Examination, Joy FM, Pambazuko, and Truth Reporting Post. Research and data analysis by Fernanda Aguirre, Romina Colman and Mago Torres of The Examination, with assistance from the investigative data consultancy Data Desk. Trade and customs data from the U.S. Census, UN Comtrade, Import Genius, Panjiva and Volza, relying on the global product code for recycled lead.

Additional Infographic design by Aaron Cole of PREMIUM TIMES.