BY OLU ONEMOLA

There’s a pothole on a side road in Abuja that, for a while now, has become the most interesting thing on my morning commute. It has not always been there. But at the beginning of this rainy season, the asphalt cracked. Then a tire or two turned the small crack into a dip, and the dip became a dent. A month later, the dent became a small crater. At that point, it wasn’t just my problem anymore—it became everybody’s problem. Traffic started to shift around it, and drivers stopped complaining and started adjusting. That’s when I started thinking: this wasn’t about the pothole. It was about what happens when something broken becomes the new normal.

In Nigeria today, oppression hasn’t started screaming; it still whispers. It doesn’t declare itself with a bang. It just shifts traffic, reroutes your path until you forget what the road used to look like. Oppression under this administration still exists in small pockets and parcels—little occurrences that, when weighed against the overall Nigerian experience, change everything so slowly that you forget it was not always like this.

Take what has happened politically in the last few months. One by one, state governments—first Delta, then Akwa Ibom—have defected to the ruling party, the APC. At first glance, this looked like politics as usual: politicians defect, alliances shift, shenanigans happen. But if you look a little closer, a pattern begins to emerge—a design, like tiles clicking into place on a bathroom floor. Now, I must say, if this were about people-centred governance or ideology, I wouldn’t bat an eyelid. In fact, I would wish the defectors well. However, this has largely been about erasing the opposition ahead of 2027, one governor and one legislature at a time.

Advertisement

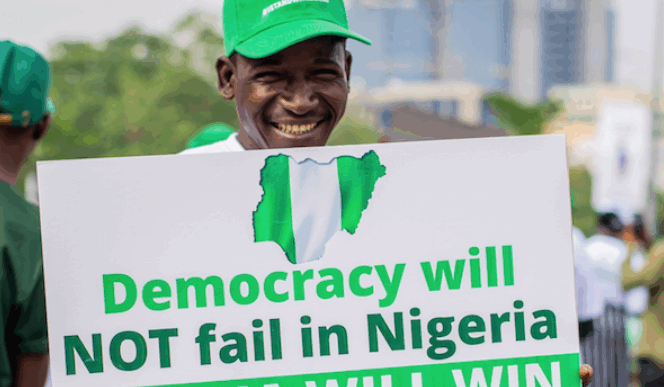

Those who are brave enough have called this what it is: the slow conversion of Nigeria’s hard-fought, hard-won democracy into a one-party state.

But those of us who should care don’t react. Like the pothole on my morning commute, we just swerve and adjust.

Or consider the strange case of “Tell Your Papa”, a song by Eedris Abdulkareem. You probably have never heard it on the radio. This is not a coincidence. The National Broadcasting Commission banned it in April, citing vague threats to “public order.” If you have heard it, whether or not you like the song is not the point. The real issue is the feeling behind it: the simmering anger of a country buckling under economic pressure. The song gave that anger a melody, and that melody made it real.

Advertisement

In a time when “On Your Mandate” is sang at official government events, the idea that a song could scare the government in power sounds absurd—until you remember that art is one of the last places where people can still say what they mean. And when that disappears, when even lyrics have to be approved, you are not in a democracy anymore. You are in something else.

But this should not be new to any of us. Like a movie with a prequel, the #EndBadGovernance protests in August 2024 gave us a grim preview of our collective potential final destination. Peaceful demonstrators. Live rounds. At least 24 killed. Hundreds arrested.

As if that was not enough, a state of emergency was declared in Rivers —effectively a political blackout. The elected governor removed. His cabinet disbanded. Just like that. Not with votes, but with an executive signature.

Power, again, didn’t come crashing through the front door. It crept in through the back, quietly. And what did we all do? Like the pothole on my morning commute, we all swerved to avoid it.

Advertisement

It is quite curious, though, that immediately the sole administrator took charge in Rivers state, the pipeline vandalism that supposedly justified the suspension of democratic rule vanished. Just like that. Not one reported incident. Which raises an uncomfortable question: was the threat real, or was it simply resolved the moment elected leadership got out of the way? Either it is a damning indictment, that order came only when democracy left, or it is a masterclass in sending a message. And maybe that message landed. Maybe the governors of Delta and Akwa Ibom were not really tired of the PDP and its mountain of problems, maybe they just saw what happened in Rivers state, took a long, hard look, and decided to swerve early, to avoid what we are all now calling the ‘Rivers Treatment.’

And while all of this has been unfolding, the institution tasked with protecting the integrity of our democracy, the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), has been busy doing something curious—not registering more than 100 new political parties. The reason, we are told, is operational. But if you take a drive around Abuja, you’ll see that billboards for 2027 are already up. The ruling party, it seems, is quietly campaigning through support groups. The race has not officially started, but the frontrunners are already on the track. As for the opposition, they are not contesting the head start. Like all of us, they seem to just be adjusting, swerving and steering around this important pothole.

Which brings us back to June 12th.

For all of us, it should be a day of memory: a nod to M.K.O. Abiola, to democracy, to resistance. But memory alone is not enough. Because memories fade. Roads change. Potholes deepen. What June 12th should be is not nostalgia—but a warning. A reminder of what happens when we stop looking at what is broken and start steering around it.

Advertisement

Because the longer we adjust, the more likely we are to forget what a straight road ever looked like.

I rest my case.

Advertisement

Onemola can be contacted via [email protected]

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.