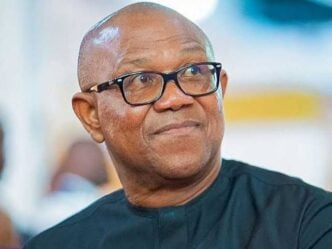

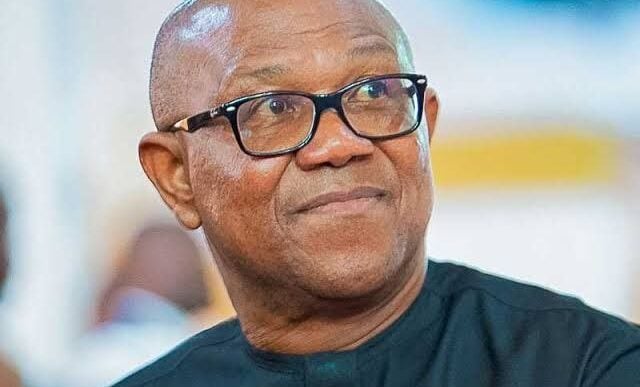

There are moments in a nation’s life when its people hear their own voices with unusual clarity. This is one such moment. In the last week of August this year, a significant event occurred—one that neither the nation’s leadership nor its citizens paused to consider fully. During that period, three voices known for their measured judgment—former Presidents Olusegun Obasanjo and Goodluck Jonathan, and the Sultan of Sokoto—spoke openly about what many Nigerians quietly acknowledge: justice in Nigeria is too often something bought, rather than earned.

When justice becomes a commodity, when money, influence, and power can sway its course, courts cease to be bastions of order and transform into markets of outcomes. The repercussions are immediate and manifold. Entrepreneurs are forced to factor in a new cost in their budgets, termed ‘friction’: the expense of adjournments, the premium for ‘speed,’ the fee for desired outcomes. Politicians shift their focus from the votes of the people to the votes of judicial officers. A nation that questions honesty with suspicion will inevitably under-invest in its future. Jonathan’s caution that capital and investments will flee when justice is up for sale is not just a political statement; it’s a mathematical truth. When contract enforcement is unpredictable and court orders are discretionary, the cost of capital rises, project timelines extend, and innovation retreats to areas where promises hold weight.

But the economic loss is only half the bill. When lawyers and the people come to believe that knowing the judge is more valuable than knowing the law, the social contract begins to tear. Citizens withdraw their trust, then their cases, then their consent. Impunity, once an exception, hardens into a weather pattern. Communities often revert to “alternative” settlements that satisfy immediate needs but erode the legitimacy of established institutions. The Sultan’s language delivered at the NBA conference at Enugu —”justice is purchasable”—sounds harsh until you watch a widow spend years on a land dispute while a developer’s injunction arrives overnight. The poor pay in time and humiliation what the rich pay in fees; both are corrosive, but only one buys results.

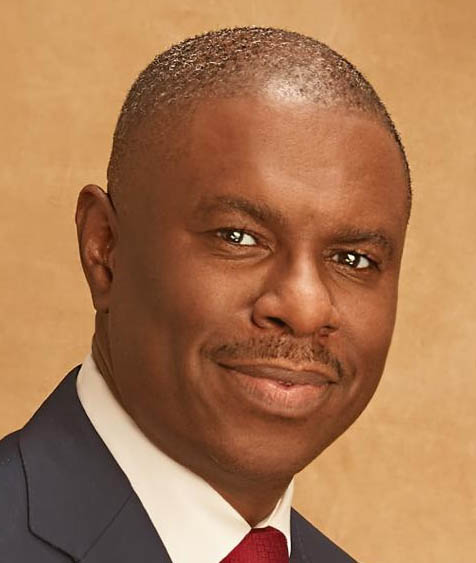

Former Vice President, a senior advocate and a law professor, Yemi Osinbajo, in 2017 cast the legal profession as an ethical bellwether—an elite with the burden of articulating what the nation must never accept. He also diagnosed the rot within corruption, ethical violations, and declining standards. A reflective moment like this demands that we hold both truths together. The law’s nobility is not a title; it is a series of costly choices. The robe does not confer integrity; it requires it.

Advertisement

Justice today in our country feels like something to buy or trade, not a fair or quick process. Cases get delayed as if time itself has value; postponements become tools for negotiation. Important decisions often happen in secrecy when they should be open. People switch courts like a game to find an advantage. Getting bail seems like a favour, not a right. Lawsuits about elections happen every season, like a business with set prices. Big business disputes freeze key parts of our economy with court orders. Human rights cases drag on until the people involved lose hope. None of this happens by chance. The system is set up—whether on purpose or by ignoring the problem—to reward dragging things out instead of solving them quickly. In the end, everyone looks for a deal instead of the truth.

Consider a simple vignette. A small factory in Aba supplies components to a larger manufacturer in Lagos. A contract dispute arises over a late payment. The smaller firm sues to enforce the contract, expecting a judgment within months. Instead, it meets a labyrinth: filings, a service that fails on technicalities; preliminary objections meant to stop the case before it starts; adjournments for reasons both grand and trivial; and finally, a transfer on “administrative grounds” that restarts the calendar. Creditors circle, workers are laid off, and equipment goes idle. By the time a partial ruling arrives, the company that needed justice has already learned a harder lesson: survival requires relationships more than rights. Multiply this story by tens of thousands, and you have a macroeconomy.

How did we arrive here? Political interference is neither a myth nor a mood; it is evident in appointments, postings, and the handling of sensitive matters, such as high-profile corruption cases or those involving powerful individuals, by particular judicial officers. Little wonder oversight is slow and opaque; sanctions are rare, inconsistent, and too quiet to be effective deterrents. Underfunding and poor welfare make virtue lonely. The procedure groans under the complexity that invites creative obstruction. Data is a stranger in our courts; we do not reliably measure the age of cases, adjournments per matter, clearance rates, or enforcement of orders. Without measurement, we perform reform by hope. Meanwhile, professional incentives, from billable hours to prestige cases, reward the art of prolonging.

Advertisement

Election disputes are the most glaring stage for our worst habits: compressed timelines on paper, elastic timelines in practice, and outcomes that feel more strategic than judicial. In commercial law, the ease with which enforcement can be stalled tells investors everything they need to know. In public interest litigation, compliance with court orders by public bodies often depends on whether obedience is politically convenient. The message to citizens is consistent and devastating: the law is negotiable.

Yet diagnosis is not destiny. If Enugu is to be remembered as an inflexion point, it cannot end with applause. It needs commitments with dates attached and levers that bite. The first lever is transparency. Publish daily cause lists with reasons for adjournment, not as ritual but as accountability. Set time standards by case type and display them in every courtroom; let litigants know when delays become deviations. Where ex parte orders are unavoidable, impose short return dates and mandatory peer review. Require early case scheduling conferences; cap adjournments with real consequences for counsel who weaponise delay. Digitise the basics—e-filing, e-service, virtual hearings where appropriate—and maintain a central, searchable judgments database. None of this is revolutionary; it is a matter of administrative will.

Discipline must be visible to deter—fast-track complaints at both the Bench and Bar. Publish outcomes. Make it career-limiting to misuse the process or to ignore orders. Compromise in any form must have real consequences and not be cosmetic. Expand commercial and small-claims courts with 90–180-day disposition targets and protect those targets from procedural sabotage. Rebuild ethics from routine to rigorous: require annual credits tied to case management outcomes and client feedback, not mere attendance. Make it costly—financially and reputationally—to trade in delay.

Beneath these quick wins lie structural reforms that decide whether improvement endures. De-politicise appointments and promotions through transparent, merit-based criteria and broad-based panels; move decisions from shadows to systems. Review judicial welfare comprehensively—remuneration, security, continuous training—because accountability without dignity breeds cynicism. Fight against executive capture of the Judiciary, as it is common today. It is alleged that the FCT minister allocated plots of land in prime areas of Abuja to some Supreme Court justices. This level of indirect abuse of the system must be condemned.

Advertisement

Simplify pleadings and narrow interlocutory appeals that reward fragmentation over resolution. Guarantee baseline funding insulated from executive whim, and pair it with procurement audits, user feedback, and performance reports. Protect witnesses and judges in sensitive cases; maintain open channels for whistleblowing that function effectively.

Mainstream ADR through court-annexed mediation and enforceable settlement protocols to relieve dockets and give businesses credible timelines. Technology is not salvation, but it is a powerful lever. A functioning e-filing system cuts queue time. Time-stamped digital services reduce the mystery of notifications. Case-flow analytics can spot bottlenecks and outliers—courts with adjournment rates that suggest either pressure or neglect.

We also need to discuss money openly. Underfunding is an invitation to compromise, but more money without rules is simply a bigger pool to waste. A protected funding architecture—multi-year budgets with ring-fenced allocations for technology, training, and security—should be coupled with independent audits and user councils that sign off on priorities.

No single institution can carry this alone. The Judiciary must own appointments, data, practice directions and discipline. Self-correcting is advocated. The NBA must police its own, raise the cost of professional misconduct, and educate the public on lawful remedies. The Executive and Legislature must provide legal scaffolding and financial guarantees without seeking leverage in return. Civil society and media must replace outrage with observation—court-watching that is careful, fair, relentless.

Advertisement

Measurement is the spine of credibility. If we cannot say how long it takes to dispose of a land case in Kano versus Port Harcourt, or how many adjournments the average commercial dispute accrues before trial, or how often public agencies comply with orders, then talk of reform is theatre. Publish the numbers. Compare them quarter by quarter. Let citizens see curves bend and ask why when they do not. Borrow external mirrors—rule-of-law assessments, enterprise surveys, arbitration seat choices—not as medals or humiliations but as prompts. What gets measured begins to matter.

There will be pushback. Politics dislikes losing leverage. Parts of the profession are addicted to the rents of delay and compromise. Capacity gaps will tempt shortcuts. Reform fatigue will whisper that nothing changes. Anticipate this. Build cross-party and private-sector coalitions that raise the political cost of sabotage.

Advertisement

Ultimately, the case for reform is not merely legal; it is also moral and economic. A nation that prizes justice will eventually find everything else too expensive—credit, jobs, peace. Conversely, a country that treats justice as a public good reaps dividends in investment, innovation, and social calm. We have, improbably, a rare consensus—from two former presidents, a revered Sultan, and a profession gathered in one city—that the old normal is unacceptable. The question is whether we will translate that consensus into norms we enforce, timelines we meet, and a culture we can be proud to hand over to future generations.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.