BY TOSIN ADEOTI

On October 21, 2025, while the rest of Nigeria debated debt and coups that never were, something quietly remarkable happened in North-West Nigeria. The governments of Kano, Katsina, and Jigawa signed an agreement to establish a regional electricity market, pledging to raise ₦50 billion to expand access to power across their states.

On the surface, it looked like a simple infrastructure deal: governors teaming up to invest in solar and grid extension. But beneath that technical language lies a much bigger idea, one that Nigeria desperately needs to rediscover: the power of regional collaboration.

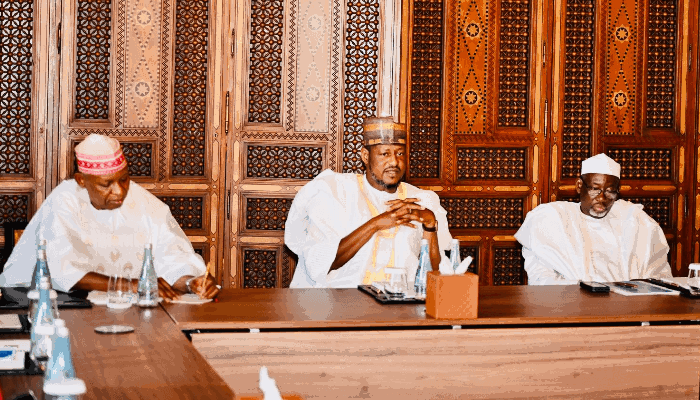

At the Marrakech Electrification Summit, where the pact was sealed, officials from the three states stood side by side, announcing their plan not only to share costs but to take equity in Future Energies Africa (FEA), the core investor in Kano Electricity Distribution Company. The goal is to fix power distribution from the ground up, together.

Advertisement

It was a small story in the news cycle that few paid attention to. Yet, for those who have watched Nigeria’s federal structure hobble innovation for decades, it was something to take a second look at.

Regional collaboration is not new to Nigeria. In fact, it built the foundations of what once worked.

In the early years after independence, Nigeria’s regions were semi-autonomous and competitive. The Western Region, under Chief Obafemi Awolowo, launched free education and the Cocoa House project, funded entirely by cocoa exports. The Northern Region, led by Sir Ahmadu Bello, built Ahmadu Bello University, one of Africa’s leading institutions. The East, under Dr Michael Okpara, set up the Eastern Nigeria Development Corporation, investing in industrial estates and palm oil.

Advertisement

Each region was distinct yet driven by a shared ambition to prove it could govern effectively. The result was economic growth and a sense of local pride that modern Nigeria can only dream of.

But the 1966 coup and subsequent centralisation of power in Abuja destroyed that balance. The federal government became the main dispenser of resources, and the states, dependent and docile, waited for monthly allocations. Regional competition turned into regional resentment.

Half a century later, Nigeria still suffers the consequences. Each state is fenced off, chasing its own small projects in isolation, without scale or strategy.

That’s why the Kano-Katsina-Jigawa alliance feels so refreshing.

Advertisement

By agreeing to build a shared electricity market, the states are acknowledging a simple truth that alone, they are too small to make meaningful progress, but together, they can achieve scale.

Kano’s Commissioner for Power, Gaddafi Sani Shehu, said the partnership is geared towards “improving electricity access and supply in the region, promoting economic growth, and enhancing the quality of life for citizens.” It’s the kind of pragmatic, technocratic thinking that, if indeed genuine, could transform regional governance.

The ₦50 billion investment might seem modest compared to the billions Nigeria borrows yearly for less coherent projects, but the symbolism matters. For once, three governors are not waiting for Abuja’s permission to act. They’re choosing self-help over dependency, efficiency over rhetoric.

They’re also making a bet on the Electricity Act 2023, which devolves power generation and distribution to states. In essence, the Act opened the door for subnational energy independence, but few have walked through it. Until now.

Advertisement

For all the promise of this northern initiative, the real tragedy is how rare such cooperation has become. Nigeria’s six geopolitical zones — north-west, north-east, north-central, south-west, south-east, and south-south — rarely collaborate on anything meaningful.

The South-West, for instance, once had grand dreams of integration under the Development Agenda for Western Nigeria (DAWN) Commission. Formed in 2013, it was meant to unify the region’s approach to transport, agriculture, and security. A decade later, it exists mostly on paper. The South-East Governors’ Forum also began with lofty goals — rail connectivity, industrial clusters, security coordination — but fell victim to rivalry and mistrust.

Advertisement

Even when crises demand unity, politics gets in the way. During the COVID-19 pandemic, states squabbled over palliatives. During the naira redesign crisis, they fought legal battles separately. The idea that states could plan together and prosper together has become almost alien.

Nigeria’s size is both a blessing and a curse. It offers vast markets and diversity, but also makes centralised governance almost impossible to manage effectively.

Advertisement

The federal government, overwhelmed by debt and political bargaining, cannot fix everything. The new $2.35 billion borrowing plan recently announced by the Debt Management Office will partly finance the 2025 budget and refinance old Eurobonds. In simpler terms, Nigeria is borrowing money to pay off old debts. That leaves little room for innovation, and even less for states to rely on federal grants.

Imagine if states across Nigeria pooled resources to tackle problems regionally: south-east states could jointly revive the Enugu coal belt or set up shared logistics hubs for Aba and Onitsha. South-west states could jointly manage the Lagos-Ibadan corridor’s transport and industrial ecosystem. North-central states could form agricultural processing zones powered by renewable energy.

Advertisement

Each zone has comparative advantages. What’s missing is collective will.

Of course, cooperation isn’t magic. The Kano-Katsina-Jigawa alliance faces real challenges. ₦50 billion is small compared to what’s needed to transform energy access. Political continuity is fragile — one election cycle can derail years of planning. The federal transmission grid still sits under Abuja’s control, requiring alignment that often slows things down.

But the alternative of each state acting alone is far worse. As things stand, most state-owned initiatives collapse before they scale. A joint regional framework can attract better financing and spread innovation faster.

If northern states can make this model work, they could provide a template for others. It would show that Nigeria doesn’t need more states; it needs smarter states.

We already have lessons on what happens when Nigerian leaders collaborate across borders. When Chief Awolowo’s Western Region shared agricultural strategies with the North in the 1950s, both regions grew. When the River Basin Authorities in the 1970s worked jointly across state lines, irrigation and food production improved before corruption and politics ruined the system.

The lesson endures: development thrives when leadership looks beyond state boundaries.

Today, as public trust erodes, it’s time for governors to rediscover that old spirit of partnership. Let them form regional councils not for press releases, but for projects. Let them share expertise and markets.

The Kano-Katsina-Jigawa electricity market might not solve Nigeria’s power crisis overnight. But it signals something important: that progress in Nigeria may no longer come from the centre, but from the cooperation of the willing.

In a country often divided by ethnicity and religion, such pragmatic alliances could do more than light up homes — they could light up hope.

Tosin Adeoti writes on society, governance, and business, weaving history and observation into stories about how people and nations evolve. He is interested in ideas that help us build fairer and more thoughtful communities. He can be contacted via [email protected].

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.