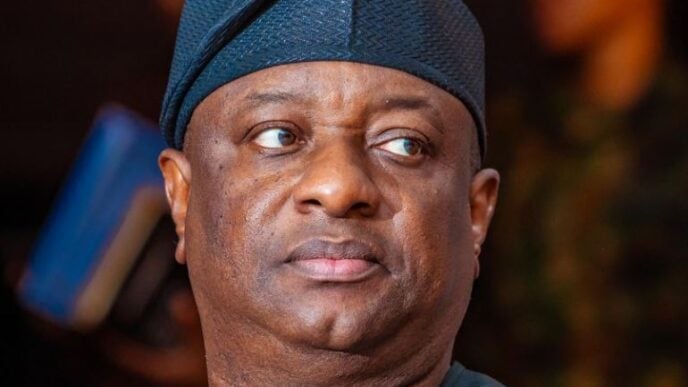

L-R: Siminalayi Fubara and Nyesom Wike | File photo

Today, as we reflect on the reinstatement of Governor Siminalayi Fubara and the Rivers State House of Assembly after a six-month suspension, it brings into sharp focus a timeless debate in governance: the intricate and often fraught relationship between the rule of law and human conscience. This is not just a conversation about what happened in Rivers, but a fundamental question about how we, as a society, should be governed.

One perspective, which many are drawn to for its clarity and structure, is rooted in legal positivism. This school of thought argues that law is simply what a sovereign authority says it is. It’s a system of rules created and enforced by the state, entirely separate from any moral or ethical judgments. From this viewpoint, an action is valid not because it feels “right” or “wrong” in a moral sense, but because it follows a defined legal procedure. The federal government’s declaration of a state of emergency, in this light, would be seen as a legitimate exercise of power, provided it was executed according to the constitutional provisions outlined in Section 305. The argument is simple: the law is the law. To deviate from it based on individual feelings or a “moral compass” would lead to chaos.

This approach champions predictability and order, suggesting that without a strict, objective framework, governance would be reduced to a subjective free-for-all, where everyone’s personal morality dictates their actions.

On the other hand, there’s a powerful counterargument grounded in the natural law tradition. This philosophy posits that there are inherent moral principles that exist independently of and are superior to human-made laws. From this standpoint, a law that violates these fundamental ethical tenets is not a true law at all. This is the perspective that emphasizes the role of conscience. The idea that “God gave us a conscience before we created judges” perfectly captures this sentiment. It suggests that while a legal action may be technically constitutional, it can still be morally wrong. The Rivers State situation, and the debate surrounding the suspension, would be seen through this lens as a moral compromise. It compels us to ask if the law, in this instance, truly served justice or merely acted as a convenient tool to sidestep a more difficult, ethical solution. This view holds that a just society must continuously strive to align its laws with a higher moral standard, and that the judiciary, in particular, has a moral obligation to ensure its rulings do not pervert justice in the name of technical legality.

Advertisement

So, how do we reconcile these two seemingly opposed viewpoints? The answer isn’t to choose one over the other, but to recognize that a just and functional society requires both. A society that adheres strictly to legal positivism without any moral introspection risks becoming tyrannical. History is replete with examples of horrific acts committed under the guise of “legality,” from the atrocities of the Nazi regime to other forms of state-sanctioned injustice, such as the apartheid racial segregation laws in South Africa. As the philosopher Gustav Radbruch argued, there are laws that can be so unjust they lose their legal character entirely.

Conversely, a society governed solely by individual conscience would be inherently unstable. Without a neutral, third-party institution like the judiciary to interpret and apply rules, disputes would quickly devolve into power struggles. The absence of a predictable system for resolving conflicts would make a functioning democracy impossible.

Therefore, the ideal lies in a delicate and dynamic balance. The constitution provides the necessary framework and predictable rules, but it is the collective conscience of citizens, legal scholars, and judges that gives that framework its moral weight and purpose.

Advertisement

The role of the judiciary, especially in a common law system, goes beyond being a detached, mechanical interpreter of the law. Their rulings are also moral pronouncements, capable of setting precedents that shape society. A judge must not only consider what the law says but also what it ought to mean to ensure justice is served. Ultimately, democracy thrives when its citizens use their conscience to hold legal institutions accountable, and when those institutions, in turn, demonstrate that the law is not a rigid, unfeeling instrument, but a living body of rules designed to serve a moral purpose: the well-being of the people. This is the delicate dance between the letter of the law and the spirit of the law, and achieving it is the ongoing work of any just society.

Adebawo is an accomplished business leader and communications expert with extensive experience in the oil and gas industry. He currently serves as the General Manager of Government, Joint Venture, and External Relations at Heritage Energy. Adebawo is also an author, scholar, and ordained minister, known for his writings on socioeconomic

issues, strategic communication and leadership.

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.