BY OLADEINDE OLAWOYIN AND FOLASHADE OGUNRINDE

Around 10 a.m. on the sunny Friday morning of 17 September, about 30 residents of Ogijo, a sprawling industrial community in Sagamu LGA, which lies on the border of Lagos and Ogun State, gathered at the Ogijo Health Centre to collect the results of their Blood Lead Level (BLL) test. As the sun baked the skin with mild intensity, they trickled into the community health facility, some with their children in tow. Tension filled the air as the residents clustered in groups to discuss their fate in subdued voices.

Months earlier, in July, their blood samples had been drawn to check for traces of lead through BLL, which refers to the concentration of lead in a person’s blood, measured in micrograms per decilitre (image.png), to assess lead exposure and its health risks. Now, the results would reveal whether the dust and smoke emitted by lead recycling companies in the Ogijo community had poisoned them.

53-year-old Thomas Ede and his three children, all under the age of 11, were among the 70 Ogijo residents whose blood samples had been drawn for testing. Mr Ede, a single father, lives 500 metres from True Metals Nigeria Limited, one of the companies that recycle used batteries for lead export in Ogijo.

Advertisement

For over 15 years, Mr Ede had called the Ogijo community home, long before True Metals began operations in the community. But about a decade ago, when the company began operations, he observed as thick black smoke from the factory’s chimneys travelled through the skies and settled daily on every possible surface, rooftops, crops, clothes, and even cooking pots. Lately, he had begun to fear that the pollution from True Metals and similar factories in the area had seeped into his family members’ bodies.

A drive around Ogijo reveals the vulnerability of its environment through the smell in the air. During the day, the atmosphere feels heavy, as if every breath carries a film of dust. At night, residents say the smoke burns their throats and leaves a bitter taste that lingers till the next morning. These recycling factories, once symbols of job opportunities and communal progress, have become agents of quiet destruction, poisoning the soil, air, and people of Ogijo.

At the community health centre, lines of worry cut across Mr Ede’s face as he sat amid a small crowd, waiting to be called.

Advertisement

Hours later, his name was read out and his worst fears were confirmed. He and all three of his children have traces of lead in their blood. But the result that broke him was that of his eldest child, eleven-year-old Freeman, whose blood showed dangerously high lead concentration at 28.47 micrograms per decilitre, more than five times the level considered safe by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

“I am really worried,” Mr Ede told PREMIUM TIMES in an interview at his residence, a one-room apartment. “I know that a lot of damage has been done to his body because of the high level of lead in his blood.”

“He has been having some symptoms, such as frequent cases of malaria and typhoid, as well as a distended stomach. His stomach is always big, no matter how little he eats,” Mr Ede added. Doctors familiar with lead poisoning explain that “distended stomach” can occur when the liver and digestive system are under stress, a common complication among children exposed to heavy metals.

Since his wife left him due to financial difficulties, Mr Ede has been raising his three children alone. He works as a farmhand, earning just enough to keep food on the table.

Advertisement

Most of what he makes goes toward rent for their small, single-room apartment and toward keeping Freeman and his siblings in school. When the blood test results came back showing dangerous levels of lead, it felt like one more blow, another reminder that survival in Ogijo comes at a cost.

Lead, a toxic heavy metal, is released into the environment during informal battery recycling. When used batteries are burned or melted, they contaminate the surrounding soil, air, and water.

The resulting fine lead dust spreads through the wind and onto household surfaces. Once inhaled or ingested, especially by children, it enters the bloodstream and accumulates in organs such as the brain, liver, and kidneys.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), there is no safe level of lead exposure. Blood-lead levels above 5 µg/dL and soil concentrations over 400 mg/kg are considered hazardous, yet many contaminated communities exceed these limits many times over.

Advertisement

Worse still, studies have linked lead exposure to lower intelligence quotient, learning difficulties, and behavioural problems. A 2020 UNICEF and Pure Earth report found that children with blood lead levels as low as five micrograms per decilitre scored up to five points lower on intelligence tests than their unexposed peers, providing evidence that no amount of lead is safe.

Sadly, Freeman’s blood isn’t the only one contaminated with lead poisoning.

Advertisement

Science of Poisoning

To understand what was happening to Freeman and dozens of other families, The Examination, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates global health threats, in partnership with PREMIUM TIMES, Joy FM, Pambazuko and Truth Reporting Post, launched an investigation and commissioned an independent scientific study to measure lead levels in the soil, as well as in the blood of workers and residents living in Ogijo community. The findings of the investigation show massive lead poisoning of humans and the environment in Ogijo.

Between April and June, environmental health researchers collected blood, nasal swabs, and soil samples to measure the scale of lead contamination. In total, 70 residents, including children, adults, and factory workers, were tested for blood lead levels (BLL).

Advertisement

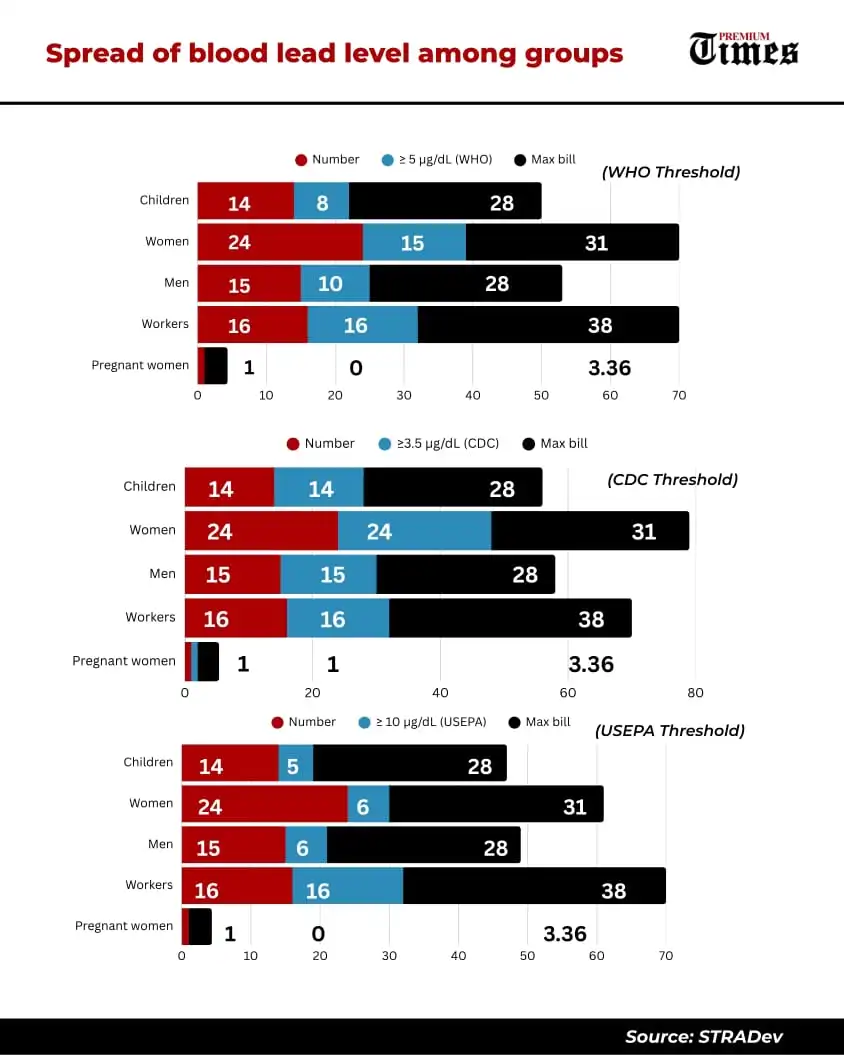

Independent laboratory tests on blood samples from residents of Ogijo and factory workers reveal widespread and dangerous exposure to lead. A report prepared by the Sustainable Research and Action for Environmental Development (SRADev Nigeria), a non-governmental environmental health organisation, found that among factory workers, the average blood-lead concentration was around 20 micrograms per decilitre (µg/dL), four times higher than the WHO’s reference limit of 5 µg/dL. Every worker was poisoned, with some recording readings as high as 38 µg/dL.

Children, who are the most vulnerable to lead poisoning, also showed alarming results. Their average level stood at roughly 12 µg/dL, with nearly three-quarters of the children tested exceeding the WHO guideline. 11-year-old Freeman’s blood contained over five times the maximum level considered safe.

Advertisement

Among other adult residents who do not work in the factories, lead levels averaged about 9 µg/dL, nearly double the WHO limit. For comparison, control samples collected from individuals outside the exposure zone showed almost no contamination, with readings below 0.2 µg/dL.

In simple terms, people living and working in Ogijo have an amount of lead that is as high as 190 times greater than those living in unaffected areas.

The soil beneath their feet in Ogijo proved just as toxic. 46 environmental samples taken from 30 locations, including soil, non-soil, and dust tests in areas where families live, farm, and children play, revealed alarming levels of lead contamination. The most shocking result came from an elementary school, where soil samples contained 1,901 parts per million (ppm) of lead, almost five times higher than the US Environmental Protection Agency’s safety limit for play areas.

Results also showed that about 80 per cent of dust and slag samples taken from homes and public spaces exceeded international safety thresholds. Dust from a hotel room that shares a fence with Everest Metal, one of the prominent companies engaged in Used Lead-Acid Batteries (ULABs) in Ogijo, contained 18,647 ppm.

Scientists also documented a link between proximity to the factories and symptoms such as stomach pain, fatigue, and poor concentration. The SRADev Nigeria report also showed that common exposure pathways include inhalation of airborne lead particles, consumption of polluted water, ingestion of contaminated food, and ingestion of contaminated soil or dust.

Residents recount their pain

For Sikirat Odufeso, life in Ogijo has become a daily struggle with illness and exhaustion. Her blood lead level reads 17 µg/dL, more than three times the World Health Organisation’s safety limit.

“I’ve been really worried since I got my result,” she said.

Mrs Odufeso, who shares a fence with True Metals, said the company initially occupied a smaller portion of land several meters away from her house. However, an expansion drive saw the company buy land from her former neighbours. Now, instead of a friendly neighbourly community, the smoke emitted daily from the lead recycling plants has been a constant challenge for her, with attendant health complications.

“It used to be just our neighbours, but now it’s just smoke. Every day, the smell and fumes enter the house. We can’t open the windows again.”

Gradually her health began to fail, she narrated, her voice a mixture of pain and frustration. Mrs Odufeso’s echocardiogram— an ultrasound test that checks the heart’s structure and function—done at the Federal Medical Centre in Abeokuta, Ogun State, and Babcock University Teaching Hospital, shows global systolic dysfunction and moderate pulmonary hypertension, meaning her heart’s ability to pump blood has been weakened and pressure in her lung arteries is abnormally high.

These conditions, which cause fatigue, breathlessness, and swelling, are consistent with the long-term effects of toxic exposure from smelting plants.

“The dust has blocked my chest,” she said. “I always feel tired. I can’t walk a long distance.”

Mrs Odufeso said she had spent over N3 million on treatment, but her symptoms persist.

The nights, she said, are the worst. “When the factories start operation, everywhere turns dark. The smoke becomes heavier. It wakes me up at night, and all the tiles and the floor will be blackened by morning.”

While Mrs Odufeso battles with her failing health, Mary Mike, a former cook at True Metals, bears an even deeper pain.

Her voice trembled as she recounted how her husband, also a worker in the same company, died in a furnace repair accident at another lead recycling plant in October 2024.

Although the company paid N8 million as compensation, Mrs Mike said she only received N1.5 million after her husband’s relatives took the rest.

Soon after the burial, she was allegedly dismissed by True Metals for taking too long to resume work. Now a widow and sole breadwinner, she struggles to care for her children.

“The supervisors do not implement any safety standards,” she said bitterly. “The safety gear is taken by the supervisors themselves. We need help. If you are not dying by fire at the company, you are dying from the smoke at home.”

Mrs Mike’s BLL result read 21.8757 µg/dL.

Children suffer too

Eleven-year-old Freeman is not the only child with worrying blood lead levels, as results show that eight out of the 14 children tested have lead poisoning of more than 5 μg/dl.

Five-year-old Sunday and eight-year-old John have a BLL of 15.006 and 24.623 micrograms per decilitre, respectively. Their mom, 49-year-old Oluwasola Bayonle (not real name), lived 500 metres from True Metals.

Mrs Bayonle recalls days when smoke and dust settled thickly over homes. The consequences, she believes, followed her into the most vulnerable moments of her life. During her pregnancy, she went into labour for three days. She said the water leaking from her body carried a strange smell.

Doctors later informed her that toxic substances, which they identified as lead, had entered her system. Her son was born at just seven months and four days. Mrs Bayonle said medical staff told her the premature birth was linked to the environment she lived in.

“They said the place was not okay at all,” she recalled.

Her worries did not end there. Her children frequently struggle with stomach pains and headaches, and medication offers little relief. When the family underwent testing, she said health workers told her the symptoms were consistent with lead exposure.

“They told me it is the lead that is causing the stomach aches and the headaches,” she said.

The emotional toll is still heavy. Some nights, the memories of her pregnancy, the dust, and the medical reports return too vividly.

“Once I remember everything, I cannot sleep,” she said. “I suffered a lot when I gave birth to my son.”

Environmental hazards at Everest Metal Nigeria Limited, where she worked as a cleaner, didn’t spare her from the fumes either. Her assigned room, used by other workers too, sat beside the furnace, where smoke pushed through gaps in the walls.

She cleaned toilets, pumped water, and earned N100,000 a month, but the constant sickness wore her down.

“It wasn’t a small sickness; some days, I had no energy. My whole body pained me,” she said.

Mrs Bayonle’s BLL test confirmed her fears, as her result showed 31.0589 micrograms per decilitre, the highest of all the women tested in Ogijo. Her children, Sunday and John, tested second and fourth highest of all children tested.

Even now, living farther away, she worries about the long-term effects on her children.

Joshua Ojo, a professor of health physics and environment at the Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, said pregnant and lactating women in exposed communities are the most vulnerable population as they often pass the lead to their babies either in the womb or through breastfeeding.

“The cases of chronic low-dose endogenous exposure of our vulnerable babies are widespread and constantly ongoing. It is affecting millions of our children, significantly degrading the quality of their lives, and consequently, our potential for development as a nation,” he said.

Schools, pupils not left out

When Adeyombo Adesoji established his school in 2010 within the Ogijo community, his goal was to provide hope for young minds through quality education. However, that goal has since been disrupted by the hazards of smoke and chemical dust from nearby lead-recycling factories drifting into his classrooms. At Fountain of the Lord’s Glory Secondary School, Mr Adesoji’s school, more than 300 pupils try to learn under a grey, polluted sky.

“When we started here, the companies around us were few and they dealt mostly in iron,” he said. “But over the years, these lead-recycling factories began to spring up. When they start production, you feel uncomfortable. The smoke, the smell, it’s choking.

“The students complain all the time. Most of them live around here, so they’re used to it, but it’s not normal,” he said.

About a decade ago, in 2015, the community decided it had had enough. Since his school had a large student population, residents asked Mr Adesoji to let the children join a protest to draw attention to the pollution.

“We all came out with placards, students, parents, everybody. We even invited officials from the State Ministry of Environment; they came, they saw the water and everything we showed them, and we thought something would finally change.”

But it didn’t.

“From what we heard, the officials collected bribes,” he said with a shrug. “But this is Nigeria, things like that happen.”

More than 10 years later, the school is still standing, still imparting knowledge in its own way, and its pupils are still inhaling the toxic smoke billowing from the chimneys of nearby factories.

This investigation, the first of a 2-part series, is reported in partnership with The Examination, Joy FM, Pambazuko, and Truth Reporting Post.