That every society is only able to go as far as their leadership takes them is a principle that is no longer up for debate. When you compare the fortunes of developed and underdeveloped economies or some of the successful brands and a long list of businesses and ideas that have died at infancy, leadership is usually the difference.

In political leadership, for example, leadership and outcome have some degree of proportionality. The quality of leadership is responsible for the sort of outcome you get. This unique burden of leadership by itself requires, therefore, that the people who aspire to leadership commit themselves to a life that prepares them for such enormous work.

This can be in the form of mentorship, volunteering, or taking on leadership roles that have little or no incentives or rewards. I also compare this period to a time of apprenticeship where those who want to lead must submit themselves to the tutelage and service of others—a period of learning from those who have walked the path before and a time to serve other people without the immediate expectation of anything in return.

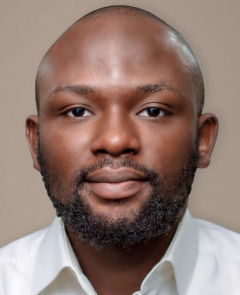

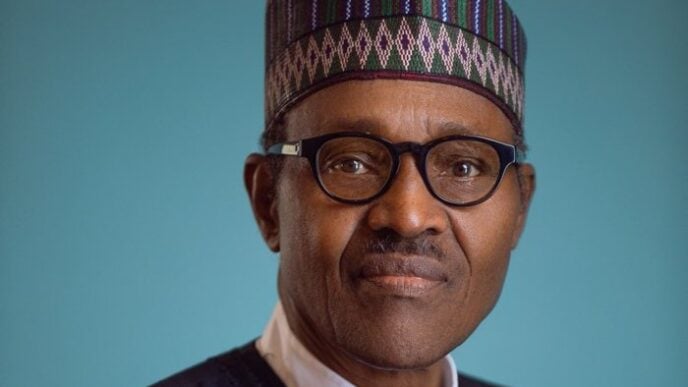

Such has been my experience over the last decade, where I have applied myself to different forms of mentorship, tutelage, volunteering and taken up leadership roles that have had little or no incentive. It has been a deliberate preparatory experience before my eventual foray into public service and a lifelong commitment to social good. During this period, I have been blessed to be nurtured by some of Nigeria’s brightest minds and had the rare honour of interacting closely with some of the most recognisable names within Nigeria’s public space.

Advertisement

From establishing a civil society in 2017 that was dedicated to active citizenship and youth engagement, to starting the annual citizens conference, championing the conversation series, leading a national mentorship programme, participating in the Not Too Young to Run campaign, serving as part of a coalition of civil societies that pushed for vital electoral amendments in 2021, providing policy insight through interventions in local and international media, writing a book that enriched the national debate, and working in key sectors of the economy, including power and financial markets.

More recently, I have also had the priviledge of serving as the president of Nigerians at Bournemouth University, United Kingdom. This was as part of my master’s in Economic Development Programme. While I did successfully complete my programme last year and celebrations are being held later this year, I was allowed to stay on as president since the society comprised current students and alumni and had an indirect impact on no less than a thousand people.

It was a welfare-centric type of society, rooted in the idea of leaving the ladder down. From helping new entrants settle into a new country, providing a pipeline of support for accommodation and part-time jobs, helping people negotiate favourable tuition plans, and rallying financial support for those who were most in need. It was a one-for-all, all-for-each kind of situation, where helping one person stay the course meant we were helping ourselves, and the testimonials are replete.

Advertisement

There are a number of key lessons that would form vital lessons for me, and I hope for aspiring and current leaders. Elections, by their nature, always leave behind a sad taste; therefore, one of the things I did at the outset was to attempt to achieve some level of consensus building. The second lesson is that leaders must show restraint and painstakingly think through decisions—analyse the cost and benefit, whether the decision would leave the people better off, and avoid hasty comments. If you have not thought through a decision, it is okay to acknowledge it but ask for more time to come to a decision; it is a sign of strength, not weakness. The truth is that leadership, by its precarious nature, does not leave room for easy choices. This is why courage is also an essential element of leadership; you must find the courage to make tough and hard decisions.

Criticisms are hard, but leaders must take them in good faith, especially the ones that are scathing and from those that are contrarian. The contrarian would never see anything good in what you do; it is hard to help them to see it, but you must show them grace and continue to treat them with respect. In any case, half of the work in leadership is managing people and interests in a way that no one feels left behind. In the end, you may find some contrarian would make a Damascene turn.

Teamwork and collaboration are at the centre of strong leadership. I have had the previledge of working with a vibrant and dedicated committee and enjoyed the overwhelming support of an expanded team. Like Hillary Rodham Clinton once admonished us, Stronger together is not just a lesson from history; it is the future we must build.

On a personal level, it has also served as a period of self-awareness and to interrogate my philosophy on whether I was right- or left-leaning and, above all, a springboard for my leadership journey. I have made my modest contribution, and I am convinced that the experience will remain a vital lesson for the future we want to build. Finally, if we must change the face of public service, those who aspire to leadership must commit themselves to experiences that prepare them for it.

Advertisement

Awogbenle, a Development and Public Policy Professional, writes from United Kingdom. He can be reached via [email protected].

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.