Parked timber trucks showing evidence of omo’s disappearing trees

In area J4, the gateway into Omo Forest Reserve, Ogun state, the air was thick with the mingled scents of damp earth and diesel fumes. Potholes pockmarked the only road in, now a ribbon of mud from days of rain. Along it, trucks groaned under the weight of freshly felled logs, their tyres splashing through puddles the colour of chocolate. Some left empty, their drivers waiting for the next load, while others carried heavy machinery deeper into the reserve. Overhead, the hum of chainsaws blended with bird calls in a daily rhythm that signals the slow disappearance of one of Nigeria’s last remaining rainforests.

For Yomi Odueke, a veteran logger who has spent 25 years in the trade, the forest is not a sanctuary but a workplace. The Ijebu-Ode-based timber contractor has made his living here, hauling wood from Omo to wherever the market will take it.

In his early years, he said, things worked differently. The sawmill ran steadily, the roads were maintained, and licensed contractors like him had clear rights to harvest timber under the supervision of the Ogun State Ministry of Forestry. But that changed when the Ministry of Agriculture, in his view, began asserting more control over the land.

“The ministry of agric has put their business here; we loggers and contractors don’t have a say anymore,” Odueke said, limping slightly as he shifted his weight.

Advertisement

The limp was the result of an attack in August 2022. He had gone into the forest to investigate reports that a group of illegal operators, known locally as alamole or “finishers”, were felling commercial trees without permits. He was with four companions when trouble found them.

“The illegal contractors attacked us with cutlasses and guns. They don’t pay any dues to the government, and the government doesn’t recognise them at all,” he recalled. In the chaos, a truck hit him as he tried to escape, breaking his leg. He spent nearly ₦500,000 on treatment at a local orthopaedic clinic. The government promised to help, but no money came.

Today, Odueke walks more slowly, but he keeps working. The forest he has known for decades, however, is vanishing faster than ever.

Advertisement

“If the government can drive away farmers and plant more trees, then we are good,” he said. “If they don’t, very soon, there will be no trees left.”

A FOREST UNDER ATTACK

The Omo Forest Reserve is more than just a patch of green on the map of Ogun state. Stretching across 130,500 hectares, this tropical rainforest is one of Nigeria’s most important ecological treasures. It was formally established in 1925 and later gained recognition as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, one of the first in Africa. The Omo River winds through its heart, feeding streams and wetlands that sustain both wildlife and people.

Its biological wealth is staggering: more than 200 species of trees, 125 species of birds, countless butterflies, and some of the last remaining African forest elephants in Nigeria, their numbers now estimated at barely a hundred. White-throated guenon monkeys leap through the canopy, while pangolins shuffle through the undergrowth at night, hunted in defiance of conservation laws.

Advertisement

In this strict nature reserve, the forest still whispers of its former glory, giant old-growth trees, foliage so dense it swallowed the light, and the rustle of wildlife that used to drown out the harsh drone of chainsaws.

But the chainsaws are getting closer.

According to Global Forest Watch, Nigeria lost 253,000 hectares of natural forest in 2024 alone — an estimated 114 million tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions. Between 2021 and 2024, 97 percent of all tree cover loss occurred within natural forests, amounting to 922,000 hectares and 405 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions. Omo forest has not been spared. Satellite data from the University of Maryland shows that between 2001 and 2018, it lost more than 7 percent of its tree cover. Conservationists warn that the outer zones where legal logging is permitted under annual licenses have already been stripped of much of their commercial timber.

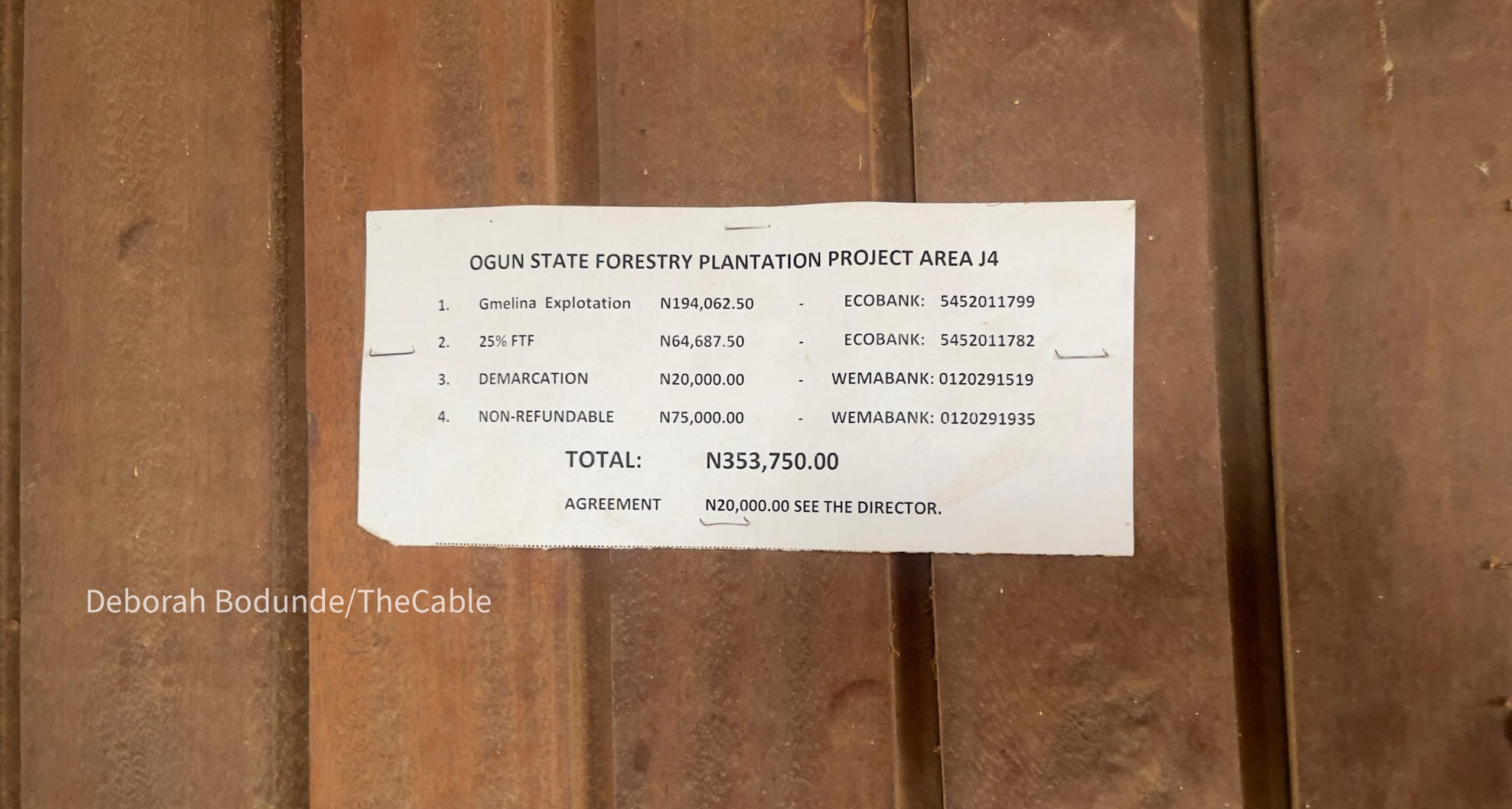

In theory, the system is designed to be sustainable. Contractors pay around ₦2 million each year for permits to harvest in designated areas, moving on only after a section is fully logged. In practice, the depletion of the outer forest has pushed many, both licensed loggers and illegal “finishers”, deep into the 550-square-kilometre conservation area, where logging is banned. There, some fell high-value trees like mahogany, gmelina, and cordia, while others clear land for cocoa farms.

Advertisement

And yet, the pressure on Omo forest is not just about timber. Nigeria’s rising population, coupled with high poverty rates, has intensified the push for agricultural land.

POLICY GAPS AND ENFORCEMENT FAILURES

Advertisement

On paper, Omo forest reserve enjoys multiple layers of protection: state forestry laws, logging permit restrictions, reserve status, and conservation partnerships with organisations such as the Nigerian Conservation Foundation (NCF). In practice, those safeguards buckle under weak enforcement, bureaucratic overlap, political interference, and daily economic desperation.

Ibigbami Oladele, divisional forest programme officer for area J4, said the reserve was originally established to protect vegetation cover while allowing limited, regulated logging. Forest officers, he explained, are tasked with daily monitoring, marking trees for felling, and ensuring each log passes inspection before leaving the forest.

Advertisement

Under concession agreements, companies like Smart Wood and Omo Wood are meant to work only in designated zones and replace each tree they cut with four to ten new ones. But those rules are wearing thin.

“Politics is now involved. And community people believe they can do anything with whatever is in the forest,” Oladele said. Certain tree species are officially off-limits because they are becoming endangered, and according to him, no more than 20 trucks of timber leave the reserve each week.

Advertisement

But field realities tell a different story. A logger, speaking anonymously, estimated that between 100 and 200 timber-laden trucks rumble out of Omo forest every month, carrying both fresh-cut and mature logs.

The state government has tried to push back. In December 2023, it ordered 17 communities it labelled “illegal farmers and timber contractors” to vacate the elephant conservation area by January 15, 2024. Whether that directive will be enforced or make a lasting difference remains uncertain.

One reason enforcement is weak is the near-total absence of modern monitoring systems in the reserve. There is no satellite tracking of tree cover loss, no reliable data collection, and in many areas, no mobile network signal.

Rangers are dispatched to patrol vast tracts of forest with nothing more than cutlasses or batons; by law, they cannot carry firearms. When confronted by armed illegal loggers, they are outmatched.

“One of the challenges we face is arresting offenders. Some try to resist arrest, and some want to fight, thereby putting the lives of rangers at risk,” said Emmanuel Olabode, NCF’s project manager in Omo forest.

Security often falls to Amotekun, a regional paramilitary outfit operating across the six states of southwest Nigeria. In some cases, forest guards and local hunters team up to track illegal activities, but these alliances are informal and underfunded. NCF is working to provide better patrol equipment and tools, while the government assists in enforcement and prosecution. But arrests are rare, prosecutions rarer still, and offenders are often back in business within days.

Even the boundaries between permitted and prohibited zones are often blurry. Some forest officials admitted that corruption seeps through the system: fake permits are issued, boundaries are ignored, and political interference blunts efforts to declare the core zone a formal wildlife sanctuary. In the absence of effective surveillance, legal loggers and farmers can stray into conservation zones, sometimes intentionally, sometimes by “mistake”.

“A stronger and effective management for the Omo forest will mean the effective protection for the largest, viable population of forest elephants in Nigeria,” said Stella Egbe, NCF’s senior conservation manager for species programmes.

Egbe noted that the crisis is systemic: scarce funding, limited equipment, and too few trained personnel in a national context where forests are treated as “waste” to be “developed” rather than ecosystems to be protected.

Omo is home to more than elephants. Its biodiversity includes the Nigerian-Cameroon chimpanzee, red-capped mangabey, putty-nosed monkey, pangolins, grey parrots, and tree species found nowhere else. Without stronger site-based management backed by political will, Egbe warned, these species will vanish.

WHERE LIVELIHOODS AND TREES COLLIDE

The fight for Omo’s future plays out far from boardrooms and policy papers. It unfolds in the dirt tracks and beneath the trees, where daily choices pit human survival against the forest’s fate.

Odunayo Odujobi, a licensed logging contractor, straddled both worlds. His operation brought an estimated ₦8 million a year into Ogun state’s coffers and kept more than 70 people employed. He proudly described himself as a government stakeholder, but now he’s confronting a different foe.

Cocoa farmers, he said, are stripping the forest to plant crops, torching young trees and driving out wildlife.

“We buy from the government and we pay huge money. But for the past two to three years, we have been facing challenges and we’re scared because the farmers are destroying and burning the trees,” he said, frustration creeping into his voice.

Sometimes, the disputes spill into violence. Farmers have chased his crew from work sites and his brother was once attacked. Odujobi claimed the ministry of forestry knew what was happening but had failed to act. He said the current situation of things is a sharp contrast to the mid-2000s when a governor ordered the eviction of illegal farmers and restored order.

“Former Governor Gbenga Daniel sent all the farmers out and the forest was peaceful. We’ve not seen that kind of governor since then. The number of people now working and making a living in this forest to take care of their families are more than fifteen thousand,” he added.

Meanwhile, loggers still pay levies for reforestation but Odujobi claimed the state rarely plants the trees it promises. Contractors try to plant some themselves, only for farmers to destroy them. Land concessions to Chinese-backed companies have further squeezed loggers into a shrinking patch of forest.

He warned that in three years, the trees could be gone. Without them, his business dies and jobless workers might turn to crime.

“If there are no trees left, I’ll sell all my equipment and get out of here. What will happen to the boys working for me? Won’t they carry guns if there’s no job?” he asked.

For now, he and his peers maintain the roads into the forest themselves.

“Help us to beg the government to take care of this place. We loggers tax ourselves millions of naira to fix the roads. If the government doesn’t take action soon, there will be more thieves and hired killers in the streets,” he said.

To Ifeanyi Moses, a driver who has worked in area J4 for nearly a decade, the roots of the problem are tangled in how money changes hands. He said farmers pay only the village chiefs, known as Baales, who keep the fees instead of remitting them to the government.

That arrangement is shifting. “Farmers have also started paying government officials at the top,” Moses explained. “The farmers now have forms and ID cards to work in this area.” The paperwork gives them legitimacy and the confidence to keep pushing deeper into forest land.

But the forest, he warned, is almost out of time. “Even the trees causing the conflict are almost finished in J4. If there are no longer trees in J4, everything will be turned into farmland.”

Moses believed loggers and farmers should be able to coexist. But his account hinted that the resources sustaining both sides are vanishing, and with them, there is no chance of a future for either.

FIGHTING FOR THE FOREST’S FUTURE

Saving Omo forest will take more than outrage. It will require dismantling the incentives that have turned its hardwoods into quick cash. But who will act, and how soon?

Andrew Dunn, senior technical adviser with the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), told TheCable that the reserve’s biggest vulnerability lies in its governance.

“Forests are not given enough political support and are managed for short-term financial gain, often by politicians,” he said.

In his view, state forest reserves like Omo are far more prone to exploitation than national parks, which are run by a federal parastatal, the National Park Service, and benefit from steadier funding and stricter oversight. He said upgrading Omo’s status could be a game-changer.

That upgrade would have to be paired with stronger laws and enforcement. Dunn called for export ban of all timber species, especially ebony, and “forcing” state governments to either protect their reserves or hand them over to the federal government.

“We should develop a system for sustainable logging outside of forest reserves and ban the export of all tree species,” he said. “We need greater oversight from the federal government to ensure that state governments stop the plunder.”

But top-down reforms are only part of the equation. Dunn and other conservationists argued that real progress depends on putting local communities at the centre of forest management.

“Community participation in forest reserve management is one of the most realistic strategies for reducing deforestation over the next five to ten years,” he said. Employing more local rangers, creating community forests, and establishing management committees are among the measures he projected as workable.

Ogun state has taken some steps. According to Olabode of NCF, a site-based management team, including a wildlife rangers unit, now carries out research, monitoring, anti-poaching patrols, and checks on illegal logging, farming, and hunting. Community engagement has been built into the strategy, with awareness programmes promoting participatory conservation and sustainable livelihoods. The state has also reviewed its forestry and wildlife law and is working with stakeholders to develop a biodiversity action plan.

Community involvement must, however, be backed by resources and training. This could mean providing alternative income streams that don’t undermine efforts to protect the forest.

Yet, as Egbe warned, these efforts still play out against a backdrop of revenue-driven forest management. The push for “green jobs” like farming is often mismatched with land availability, leaving reserves open to encroachment. At both state and local government levels, the lure of revenue, whether legally sanctioned or illicit, compromises conservation goals.

Egbe added that policymakers must recognise the link between forest health and national well-being. Protecting keystone species safeguards far more than wildlife, but also preserves watershed health, carbon storage, nutrient cycling, and erosion control. She argued that consistent monitoring, capacity building for enforcement agencies, and integrating science into decision-making are critical for the forest’s survival.

International actors also have a role to play. Dunn urged donors and conservation organisations to commit to long-term funding, maintain greater scrutiny of projects, and “criticise the government when necessary”.

Without that pressure, well-meaning reforms risk being swallowed by the same political interests that have allowed Omo forest’s decline.

This article was produced in partnership with Wild Africa.