Government Chest Hospital, Ibadan, Oyo state capital, a major TB treatment centre

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

When the spine leans low beneath the weight of the world, that is when the sky sends its final stone, an African adage says. Such an unexpected blow can be devastating, as it comes at a time when you are vulnerable. The impact is felt instantly. It breaks you down in that wobbly state. Recovering then becomes a crossroads of chance.

That was exactly what happened on January 20, 2025, when United States President Donald Trump issued an executive order to halt all foreign aid and disbursements, except for food assistance. Executive Order 14169 affected the Agency for International Development (USAID), the world’s leading international development agency responsible for billions of dollars in US aid projects across the world.

In March, Marco Rubio, the US secretary of state, announced that the Trump administration had cancelled 83 percent of USAID’s programme. Rubio said the agency had disbursed over $715 billion over the years, and now America is redirecting the funding into domestic affairs.

Advertisement

By July, the USAID was officially shut down, and decades of global development work came to a shocking end. The ripple effect was felt across the world, especially in global health and other humanitarian efforts.

For the developing world, especially Sub-Saharan Africa, where the health sector is poorly funded by the government and healthcare infrastructure is in near shambles, the announcement was the straw that broke the camel’s back. The move disrupted ongoing health initiatives, especially AIDs, tuberculosis (TB) and malaria, often referred to as ATM.

A NATION’S BURDEN

Advertisement

For Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, most healthcare intervention programmes are donor-funded. In 2023, Nigeria was one of the top 10 recipients of USAID funding, getting over $600 million in health grants. The agency disbursed about $2.8 billion to Nigeria’s health sector between 2022 and 2024, which went primarily to fight HIV/AIDS, malaria, polio, and tuberculosis.

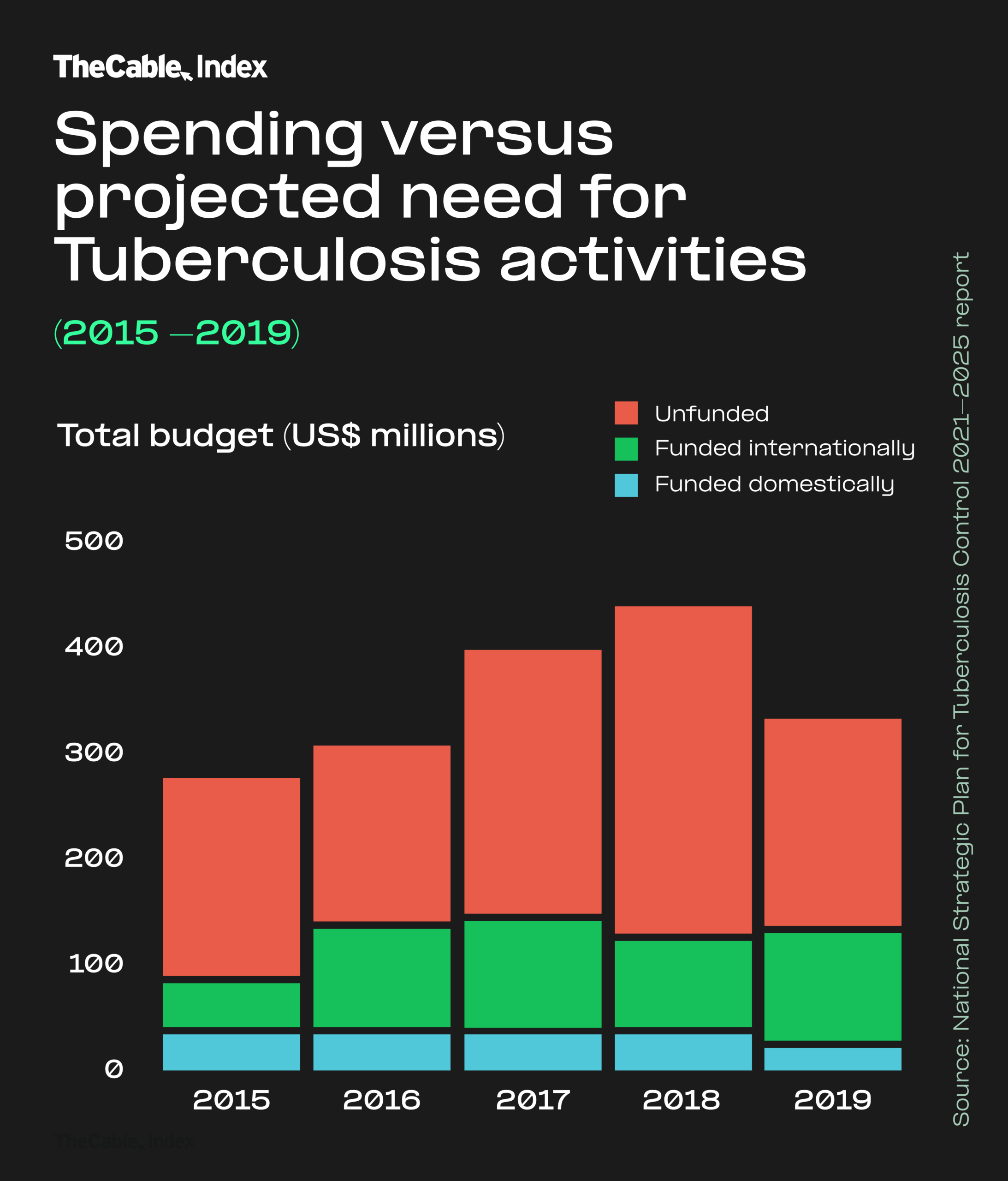

Out of the country’s $388 million annual budget for TB, 6% is domestically funded, 24% is donor funded, while 70% remains unfunded, with the United States contributing $22 million.

Tuberculosis is an airborne disease caused by a virulent bacterium known as Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Despite being preventable and curable, TB has been identified among the top 10 causes of death worldwide. According to estimates, one missed case can transmit the infectious disease to 15 people in a year.

At the moment, Nigeria has the highest tuberculosis burden in Africa and the sixth highest globally. The disease kills 268 Nigerians every day. According to available data, the country recorded its highest-ever TB notification rate in 2024, identifying over 400,000 cases, about 79 per cent of the estimated 506,000 cases. Of over 361,000 cases reported in 2023, 9% of them were children. Nevertheless, TB cases were under-reported, increasing the high risk of transmission.

Advertisement

USAID funded the Tuberculosis Local Organizations Network Project (TB-LON) across Nigeria’s high-burden states. The agency worked with local Nigerian NGOs, community-based organisations, and health facilities to expand TB services beyond hospitals into local communities.

However, the global funding cuts have disrupted the TB programmes in 18 states in Nigeria. The Global Fund office in Nigeria says the country needs $404 million to deliver TB treatment and services in 2025. Without external funding, patients are expected to cough out about $3,000 for drug-resistant TB treatment, in a country where over half of the population is multidimensionally poor and living on less than $2 daily.

In March, Ibrahim Tajudeen, executive secretary of the Global Fund Country Coordination Mechanism (CCM) in Nigeria, said the TB drugs allocated for 2025 had been used to meet the treatment demands for 2024, while he disclosed that the US funding withdrawal has created a $5 million funding gap.

As soon as the executive order came into effect, health workers employed by development agencies to man clinics, especially in remote communities, withdrew their services immediately.

Advertisement

WHEN THE MONEY STOPS COMING

In Osun state, south-west Nigeria, where over 250 community extension workers funded by donors immediately left the system, the public healthcare staff felt the move. Some of the primary healthcare centres with a handful or no healthcare workers were left stranded. Nurses and doctors became frustrated and exhausted as one staff member is now expected to take on the job of four.

Advertisement

At the State Specialist Hospital in Ashubiaro, Osogbo, Osun state capital, the chest clinic was unusually quiet. Face contorted with anger, the middle-aged nurse in white hijab spared 53-year-old Adegboyega no words. For the past three hours, she had gently attended to tuberculosis patients who had come for their bi-weekly treatment at the clinic. As she dispensed drugs, she admonished them and offered hope.

But this time around, with just about two nurses on duty, she seemed to have exhausted her gentility as much as her strength. The thought of a patient not taking his medication at a crucial period, when such expensive drugs are nearing depletion, irked her. Adegboyega’s wife, who escorted him to the clinic, had reported him to the nurse.

Advertisement

“You’re wasting our efforts, and that is not good enough,” the nurse challenged him.

“We told you to stop drinking alcohol and herbal concoctions. Your tests and drugs are expensive, but you get them free. We’re helping you, but you’ve refused to help yourself.”

Advertisement

There was awkward silence at first. Adegboyega, a commercial driver, found himself groping for words. He kept silent for a while. Then he promised to turn a new leaf. He hopes to get better soon and resume his job.

Abdullahi, a resident of Iwo Town and a commercial motorcyclist, wasn’t as lucky as Adegboyega. Tall, dark and slim, he was in his 40s. He lived adjacent to the Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Clinic in the ancient town, where he had easy access to free treatment that could have saved his life. But he wouldn’t take his drugs. He’d branch at the clinic to collect his share of the money meant for TB patients, return to the shade of the big tree near his compound, and discuss with friends.

When Abdullahi’s friends got wind of his condition, they stopped him from joining them under the tree. His wife also left him with their three children. The staff at the clinic begged him to take his medicine; neighbours would buy food for him just to encourage him. But he’d rather sit in front of his compound alone, gulp sachets of alcoholic drinks, expel tons of dry cough, while waiting to get some respite and return to ferry passengers across the town on his motorcycle.

His condition, which started as susceptible TB, became drug-resistant. When his health deteriorated, his relatives took him to their village, where he died three days later. Under the tree where Abdullahi used to sit with his friends, some of whom later tested positive for TB, has now become a mobile clinic.

For Timilehin, a young petty trader in Osogbo, who had spent over N40,000 ($27) on typhoid treatment after he was misdiagnosed at a private clinic, the golden advice he got from his neighbour to visit the government hospital for a free screening was a lifesaver. He was properly diagnosed, and he has been receiving free treatment since April.

One of the state officials in charge of TB programmes, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said donors used to pay drug-resistant patients monthly for the period of free treatment to encourage them. It started from N3,000 ($2), then to N6,000 ($4), N10,000 ($7), N25,000 ($17) and later N35,000 ($23).

“They were mostly poor locals, and they complained that they didn’t have money for transport from their house to the clinic. They also complained that they didn’t have money for food because most of their family members had abandoned them for fear of infection. We also give them food just to encourage them to comply,” the official said.

“They can’t work during treatment, and they often hate themselves because of the disease. They hardly move around because of the stigma. Everyone avoids them, and they don’t want to be seen in places where they are known. The money we gave them might not be enough to feed them in a month, but it really encouraged them to buy some nutritious food and come to the clinic often.”

Grants are gone, donor-funded staff are disengaged, reagents are drying up, drugs are depleting, and financial incentives are no longer available for patients. What’s the current situation on the ground?

CASE DETECTION IS DROPPING

According to the state TB official, all the equipment used for TB was imported and paid for by donors who got their funds from the American government. From portable digital x-ray machines to rapid diagnostic kits, GeneXpert machines, TruNat, and other radiological tools, the equipment run into millions of dollars.

With the disengagement of partner staff who operated the machines and visited remote communities for house-to-house outreaches, contact tracing, and screening, cases are dropping.

The total TB cases diagnosed in Osun in 2024 were 22,031. State officials fear the figure might reduce in 2025. For instance, at the Alaye Primary Healthcare Centre in Iwo Town, the facility with the highest TB burden in the state, 612 cases were reported in the first quarter of 2025, then it dropped to 311 in the second quarter.

“We have a shortage of reporting and recording tools,” the TB official told TheCable. “The sector was already struggling with low staff. Before, there was no counterpart funding from the government for these programmes, as we solely relied on donors. Now, the government is trying to recruit more officials.”

“The workload is much, and it is not possible to cover the areas of the partners who left, which is the reason the cases dropped, as we could not detect more. We had a shortage of drugs last quarter; we got a supply in the second quarter. Due to low case detection, there are still drugs. Our data is coming down because of the funding withdrawal. We screen patients all over; now, nobody is there to screen them. So, the case will go down to zero.

“In Q3 of 2024, in Osun, there were over 7,000 cases. We were trying to bring it up when the US executive order came early this year, and it brought the number down. Q1 2025 was 4,525. We’re currently collating the numbers for Q2 2025, and we can’t tell what the present data says. It might be less.

“TB is an airborne disease. We are sitting on a keg of gun powder which can explode anytime.”

THE COST OF NEGLECT

In all this, there is a silent threat – patients with TB/HIV co-infection. During sensitisation programmes at the public health centres, officials describe TB and HIV as “husband and wife” – two diseases whose treatments come from donor funding. When a patient contracts HIV, their immune system is suppressed, and it cannot fight against some infectious diseases, especially TB. This co-infection leads to higher morbidity and mortality rates compared to a single infection, and it strains the healthcare system.

According to the 2021 national guidelines for the management of TB/HIV co-infection in Nigeria, HIV is known to increase the burden of TB, while TB is the leading cause of death among people living with HIV and was responsible for one-third of the estimated 690,000 deaths from HIV in 2019.

In Oyo state, 14,930 TB cases were diagnosed and treated in 2024, including 738 HIV co-infections. It was worse in 2022 when roughly 20% of TB patients in the state also lived with HIV. If the drugs for TB and HIV are no longer available, that leaves the fate of patients with co-infection hanging in the balance.

The objectives of the National Strategic Plan for Tuberculosis Control 2021–2025, a policy document to end the TB epidemic in Nigeria, include strengthening the provision of integrated services for all co-infected with TB and HIV.

The budget required to implement the ambitious five-year strategy was pegged at $1,944,925,000, and the bulk of it was expected from external donors – USAID and The Global Fund.

For instance, in 2020, Nigeria received a grant of $890 million from the Global Fund to reduce the impact of HIV, tuberculosis and malaria from 2021 to 2023.

In 2021, USAID donated 86,500 GeneXpert Ultra cartridges to the national tuberculosis (TB) and leprosy control program. Two years after, Global Fund approved $1 billion for TB, malaria and HIV for another three years.

The policy document says the domestic funding for TB control in Nigeria is very low, stating that only 8% of TB interventions are funded locally, while 32% is funded by international donors. This leaves an existing gap of 60% of the required funding for TB programmes.

One of the new strategic directions for the strategic plan is domestic resource mobilisation — in-country funding of the TB budget. The question on the lips of some stakeholders remains: What is the government doing to raise domestic funds to forestall an imminent crisis?

In May, while addressing a joint session of the national assembly, President Bola Tinubu said no amount of foreign aid would help Nigeria unless citizens unite to build the country.

“No amount of aid from foreign countries can help us. Let us work together to build our nation, charting a new path,” the president said.

Earlier in the year, the national assembly approved $200 million to cater to health initiatives impacted by the US executive order.

TheCable contacted Alaba Balogun, head of press and public relations at the Federal Ministry of Health, asking questions on what the Nigerian government is doing to bridge the gap left behind by foreign donors and if domestic funding has actually been released to support ongoing health programmes. No response has been provided to date.

A senior government official at the Ministry of Health in Osun said the state government is also trying to raise over a billion naira to bridge the gap that is already becoming obvious.

“The TB programme was doing fine, and we were moving towards the point of sustainability with the help of donors. Actually, we’ve got to the level of epidemic control in TB, but if we don’t sustain the successes of the pre-Trump regime, patients will develop drug-resistant TB,” the official said.

“We may have a surge. There are some communities that are not easily accessible. We had people who could take drugs to patients at home. We had community testers, officials who stayed in these hard-to-reach areas. But they have been disengaged by partners who hired them.”

In a chat with TheCable, Happy Adedapo, Oyo state chairman of the Nigerian Medical Association (NMA), said the withdrawal of foreign funds portends great danger to the Nigerian healthcare system.

He said blaming a foreign country for withholding its funds is not the way out, but the government must look inwards, cut down on “frivolities and extravagance” to take care of its citizens.

“I foresee a crisis of pandemic proportions. I can tell you categorically now that there is a resurgence in the incidence of HIV/AIDs. New cases are being recorded, unlike in the past when people had access to drugs and viral loads were reduced to the barest minimum. But now, these drugs are no longer readily available. The viral loads are increasing, which aids transmission easily,” Adedapo said.

“I’ve said this before. When the political elites are affected by anything, they jump up and ensure their interests are protected. Now that HIV and tuberculosis may not touch them, we have to appeal to them. We knew what happened during the COVID pandemic. They could not fly out, the foreign destinations were locked against them, and the political elites looked inwards. They raised emergency funds and set up emergency centres, and the prediction of some foreign powers that people would drop dead on African streets didn’t come to pass because of the actions some of our leaders took at that time. The question to ask now is: where are those emergency and infectious centres set up during the COVID period? They have become moribund. Why should we allow another pandemic to come before we start creating emergency solutions?

“There’s this saying that adversity may actually bring out the best in you. With the lack of funds from foreign donors, it should be an opportunity to strengthen our capacity. If we put so much into the system, we should expect something good.”

TB remains a major public health threat. While the world is working to end the TB epidemic by 2030 — a goal set within the Sustainable Development Goals — funding constraints could pull a major setback, especially in underdeveloped countries.