BY ADAEZE OREH

In mid-July, when the international humanitarian organisation Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) raised the alarm on rising cases of malnutrition, and its devastating long-term consequences, there was a global outcry.

Certainly, malnutrition in Nigeria is not new, and over the years, has stemmed from inflation, food insecurity, inadequate healthcare infrastructure, security challenges, and disease outbreaks worsened by low vaccine coverage. However, with recent severely detrimental international funding cuts, the country’s sub-optimal nutrition response has gravely worsened, constituting one of Nigeria’s worst nutrition emergencies in decades.

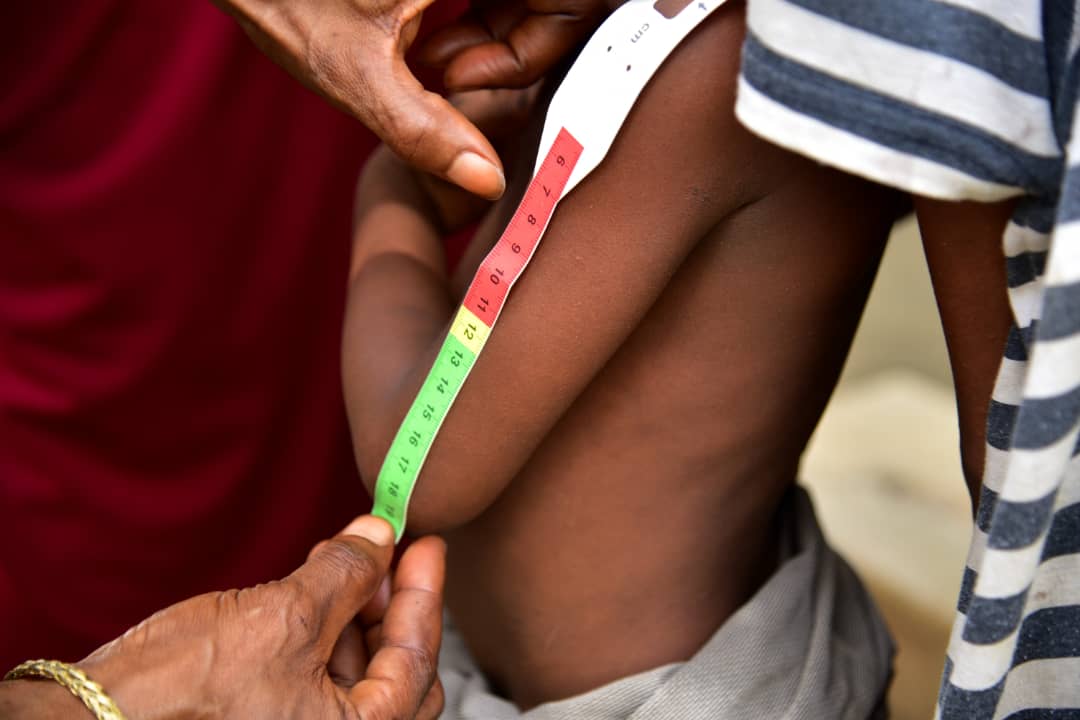

Malnutrition is a direct or underlying cause of 45 percent of all deaths of under-five children, and Nigeria has the second highest burden of stunted children in the world, with a national prevalence rate of 32 percent of children under five. Recent data from the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) paints a troubling picture. An estimated 12 million Nigerian children under five years are stunted – a sign of chronic malnutrition – while over 2 million suffer from wasting, a severe and life-threatening condition. Despite this high burden, only two out of every 10 children affected can access the treatment that they need. Whilst children bear the larger brunt of the condition, about seven percent of women of childbearing age also suffer from acute malnutrition.

Advertisement

Although northern Nigerian states are most affected by stunting and wasting, southern states also have significant burdens. In oil-rich Rivers State, active surveillance of cases of malnutrition in late 2024, revealed stunting rates of 10.9%, underweight 7.6%, and wasting 5% in children below the age of 5 years.

Nonetheless, malnutrition is not the only face of hunger. In wealthier households, diets overloaded with sugar, salt, and processed foods are quietly fuelling non-communicable diseases such as hypertension, diabetes and heart disease. High rates of malnutrition therefore pose significant public health and development challenges for the country. Stunting, which has an increased risk of death, is also linked to poor cognitive development, a lowered performance in education and low productivity in adulthood – all contributing to economic losses estimated to account for up to 11 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

Advertisement

Government and aid organisations are trying to fight back, but their reach is patchy. Community health programmes exist, but many clinics are understocked and understaffed. International agencies send ready-to-use therapeutic foods (RUTFs), yet these don’t always make it to every child who needs them, as they are mostly imported at enormous cost. Nigeria will not break free from malnutrition’s deadly grip by treating it as an occasional emergency. It requires a deliberate, united, and sustained response. Therefore, without a holistic plan that aligns all efforts in the same direction, these gaps will keep swallowing young, vulnerable lives.

First, globally, food prices have soared beyond the reach of millions, turning balanced meals into a luxury. Healthy food can be made more affordable through targeted subsidies, fair market regulation, stronger local food production, and robust distribution mechanisms. Also, nutritional support for women in communities who have recently conceived will avert malnutrition in pregnancy and lactation. Supporting small farmers, especially women, can create steady supplies of nutrient-rich foods and shield communities from the volatility of imports. Moreover, food security is impossible without physical security. In rural areas, fields lie abandoned as farmers flee violence, leaving markets empty and plates bare. Restoring safety in these agricultural zones is thus as critical as planting crops. Also, displaced farmers must be equipped with seeds, tools, and land to begin producing again when conditions allow. Additionally, the domestic manufacturing of RUTFs which are the mainstay of management of severe acute malnutrition needs to be expanded for more sustainable access and availability. In the words of His Royal Highness, Muhammad Sanusi II, 14th Emir of Kano, Chairman Board of Trustees of the Nutrition Society of Nigeria, “The future of nutrition in Nigeria must be multisectoral, technically sound, and politically anchored.”

Advertisement

Second, without clean water, safe sanitation, and basic healthcare, available food can be wasted, as a child battling constant diarrhoea or infections cannot benefit from the nutrients they consume. Nutrition programmes must be interlaced with other public health efforts, through genuine collaboration between government, aid agencies, civil society, and communities. Nigeria’s recently launched Nutrition 774 Initiative programme driven by the Presidency has enormous potential to encourage the convergence of high-impact nutrition interventions at the grassroots level if robustly adopted by states for significant improvements in nutrition outcomes across Nigeria’s 774 Local Government Areas (LGAs). Community health systems must also be strengthened. A health facility without trained staff, medicines, or therapeutic foods cannot save lives. These centres should offer treatment and ongoing nutrition education that empower families to make healthier, affordable, daily nutritional choices. In January 2024, the Rivers State Government led by Governor Siminalayi Fubara established Integrated Management of Acute Malnutrition (IMAM) sites in designated primary healthcare centres and general hospitals across the state specifically to prevent and treat severe acute malnutrition and build local personnel capacity.

Through a comprehensive approach, Nigeria can loosen malnutrition’s hold on its children and future. Adequate nutrition is not a privilege, but a fundamental human right, so, we can no longer afford half-measures or fragmented efforts.

Every child lost to malnutrition is a loss to Nigeria’s future, and every moment of delay deepens the crisis. We must act with the same urgency with which we would approach any national emergency — because that is precisely what this is.

Advertisement

If we nourish our people, we strengthen our nation; if we fail, we pay the price for generations.

Dr Adaeze Oreh is a Kofi Annan Global Health Leadership Fellow, Senior Fellow Aspen Global Innovators, Consultant family physician, public health expert and advocate for affordable universal healthcare for all Nigerians. She is the Honourable Commissioner for Health in Rivers State, Nigeria, and recently chaired the Opening Ceremony of the 2025 Annual General Meeting and Scientific Conference of the Nutrition Society of Nigeria which held in Port Harcourt.

Advertisement

Views expressed by contributors are strictly personal and not of TheCable.